Introduction

Psychological test construction involves several key steps designed to ensure that the test accurately measures the targeted psychological traits or behaviours. Kaplan and Saccuzzo (2005) defined a psychological test as “a set of items designed to measure characteristics of human beings that pertain to behaviour.” This includes aspects such as emotional functioning, cognitive abilities, personality traits, and values.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), a psychological test is any standardized instrument used to measure behaviour or mental attributes, such as attitudes, intelligence, reasoning, comprehension, abstraction, aptitudes, interests, and emotional and personality characteristics (APA, 2023). These tests can include scales, inventories, questionnaires, or performance-based assessments, all designed to provide valid and reliable data on human behaviour.

Steps in Test Construction

Steps in Psychological Test Construction

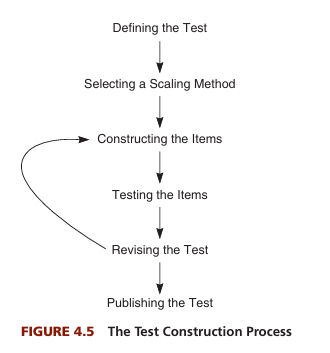

There are generally seven steps involved in constructing a psychological or psychometric test. These steps ensure the test’s reliability, validity, and applicability across different contexts. According to Greogory (2015), these include-

1. Defining the Test

Planning is the foundation of any well-constructed test. It begins with a clear definition of the test’s objectives, ensuring alignment with the specific behaviours or traits being measured (Anastasi & Urbina, 2009). During this phase, the following aspects are addressed-

- Defining Objectives– The first step in psychological test construction is clearly defining the objectives. This involves determining exactly what the test aims to measure, such as intelligence, personality traits, or specific cognitive abilities. For instance, an intelligence test like the WAIS (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale) may focus on assessing verbal comprehension, working memory, and processing speed. Each objective informs the content and structure of the test, ensuring it aligns with the intended psychological trait or behaviour being measured (Kaplan & Saccuzzo, 2005).

- Determining Content– After defining objectives, the next step is determining the type of content the test will include. This involves deciding whether the test will consist of multiple-choice questions, short answers, essays, or performance-based tasks. For example, while the WAIS includes both verbal and performance-based items to measure intelligence, a personality test may rely more on self-report inventories. The content must reflect the objectives and be suitable for the intended population.

- Test Format– Once the content is determined, a detailed test format or blueprint must be created. This blueprint specifies the number of questions, the time limit for the test, and the methods of sampling test items (Singh, 2006). For example, aptitude tests like the SAT must balance a mix of questions and time constraints to assess a range of abilities. The format should ensure that the test is comprehensive and manageable for both test administrators and test-takers.

- Instructions and Scoring- Clear, concise instructions are crucial for both test-takers and administrators to ensure consistency in administering and scoring the test. These instructions include how the test should be taken, how responses should be recorded, and how the test should be scored. For instance, tests like the WAIS provide detailed scoring procedures to measure various subdomains of intelligence accurately.

2. Selecting a Scaling Method

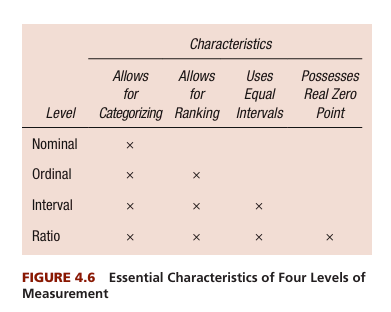

Once the test’s purpose and objectives have been defined, the next step is to select an appropriate scaling method. Scaling refers to the way responses will be scored and interpreted. Different types of scaling methods are used depending on the type of trait or ability being measured.

- Nominal Scale- The simplest form of scaling, where items are classified into categories without any rank order. An example would be a test that asks respondents to check off their gender or race.

- Ordinal Scale- Items are ranked in order, but the intervals between rankings are not necessarily equal. For example, in a job performance test, employees might be ranked from “excellent” to “poor,” without specifying how much better “excellent” is compared to “good.”

- Interval Scale- This type of scaling involves equal intervals between points, but there is no true zero point. An example would be a temperature scale, where the difference between 20°C and 30°C is the same as between 30°C and 40°C.

- Ratio Scale- In this scaling method, there are equal intervals, and a true zero point exists. This allows for meaningful comparisons of ratios. For example, a test measuring reaction time would use a ratio scale because a reaction time of 0 seconds means no response.

The choice of scaling method is crucial for ensuring that the test accurately reflects the construct being measured and allows for meaningful interpretation of results (DeVellis, 1991). For instance, in an intelligence test, interval scaling may be used to show differences in IQ scores, while a personality test may use an ordinal scale to rank respondents on traits such as extraversion or agreeableness.

3. Representative Scaling Method

Scaling methods in test construction involve various techniques to quantify and measure psychological constructs, ranging from expert ranking and equal-appearing intervals to Likert scales and empirical keying. Some of the most popular scaling methods are-

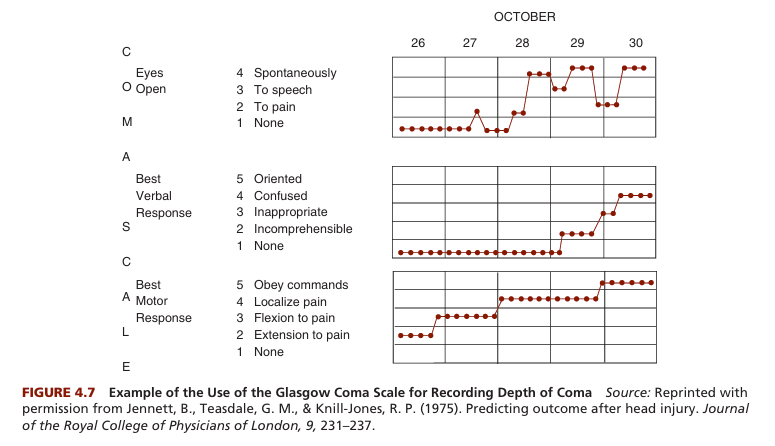

- Behavioural Expert Rankings- To measure the depth of coma in head injury patients, experts can be asked to list behaviours indicative of different levels of consciousness. These behaviours are then ranked along a continuum from deep coma to basic orientation. The Glasgow Coma Scale, developed by Teasdale and Jennett (1974), is a notable example.

- Equal-Appearing Intervals- Developed by L.L. Thurstone, this method is used to construct interval-level scales from attitude statements. It involves creating a broad set of statements about an attitude, having judges sort these statements into categories ranging from extremely favourable to extremely unfavourable, and then calculating the average favourability and standard deviation for each item. Items with large standard deviations are discarded to ensure the final scale provides reliable interval-level measurements.

- Absolute Scaling- Also developed by Thurstone, absolute scaling measures item difficulty across different age groups. By administering the same test items to various age groups and comparing the difficulty levels, researchers can determine where each item falls on a scale of difficulty.

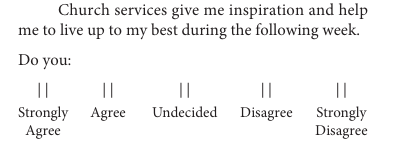

- Likert Scales- Proposed by Rensis Likert, this method assesses attitudes using a simple approach. Respondents are given a set of statements with response options ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Each response is assigned a numerical score, and the total score is calculated by summing these values.

Likert Scale

- Guttman Scales- Developed by Louis Guttman, Guttman scales are designed to measure a unidimensional continuum. Items are ordered such that endorsing a more extreme statement implies agreement with milder statements. For example, in the Beck Depression Inventory, items are arranged so that endorsing a severe symptom indicates agreement with less severe symptoms as well.

- Empirical Keying- This method involves selecting test items based on their ability to differentiate between criterion groups, such as depressed versus non-depressed individuals. Items are chosen for their ability to contrast these groups effectively, regardless of theoretical considerations. The final scale is constructed based on the frequency with which items are endorsed by the criterion group compared to a normative sample.

- Rational Scale Construction- This approach, also known as internal consistency, focuses on developing self-report inventories where all items are designed to correlate positively with each other and the total scale score. Items are created based on a theoretical understanding of the construct being measured. After administering these items to a large sample, researchers analyse item correlations to refine the scale, ensuring that it accurately measures the intended construct.

4. Constructing the Items

Item construction is a critical phase in test development and involves creating the actual test questions or prompts. The quality of the test items directly influences the test’s reliability and validity. DeVellis (1991) provides several guidelines for item writing:

- Define what you want to measure- Test items should clearly reflect the construct being assessed. For instance, if the test is intended to measure emotional intelligence, the items should be designed to assess emotional regulation, empathy, and social skills.

- Generate an item pool- It’s important to create a large pool of items initially, from which the best ones can later be selected. Items should vary in difficulty and complexity to ensure they assess the full range of the construct.

- Avoid double-barrelled items- Double-barrelled items are those that ask about two different things in the same question. For example, a test item that asks, “I enjoy reading books and going to movies” is problematic because respondents may agree with one statement but not the other.

- Keep reading level appropriate- The difficulty of the language used in the items should be suitable for the test-takers. For example, if the test is intended for children, the items should be written in simple, clear language.

- Mix positively and negatively worded items- To avoid response biases such as acquiescence (the tendency to agree with items regardless of content), it’s important to include both positively and negatively worded items. For instance, in a self-esteem test, one item might say, “I feel good about myself,” while another might say, “I often feel worthless.”

- Use appropriate formats- The item format (dichotomous, polytomous, Likert scale, etc.) should be chosen based on the type of response needed. For example, knowledge-based tests often use multiple-choice items, while personality tests may use Likert scales.

By adhering to these guidelines, test developers can ensure that the items accurately measure the intended construct and provide reliable, valid results.

5. Testing the Items

During test development, psychometricians expect many items from the initial pool to be discarded or revised. To address this, they create an initial surplus of items—often twice the number needed. The final selection of test items involves a thorough process of item analysis using several statistical methods to determine which items should be retained, revised, or discarded. Here’s a detailed summary of the key methods used in this process:

- Item-Difficulty Index- This index represents the proportion of examinees who answer a test item correctly. Values range from 0.0 (no one answers correctly) to 1.0 (everyone answers correctly). Items with difficulties around 0.5 are typically ideal because they provide the most information about differences between examinees.

- Item-Reliability Index- This index assesses the internal consistency of items by correlating each item with the total test score using the point-biserial correlation coefficient. It can be measured as-

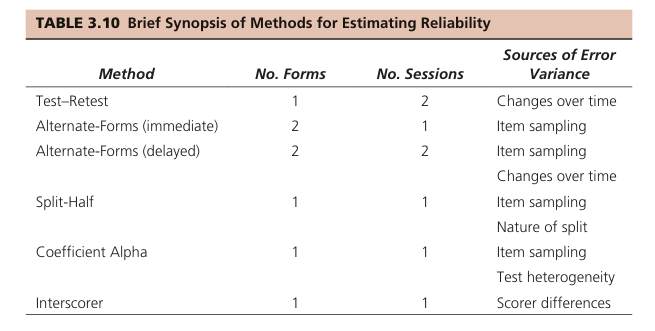

- Across time (test-retest reliability)- examines the stability of test scores over time. It involves administering the same test to the same group of individuals on two different occasions and comparing the scores.

- Across items (internal consistency)- assesses how well the items on a test measure the same construct.

- Across different researchers (inter-rater reliability)- evaluates the consistency of scores assigned by different raters or judges.

- Item-Validity Index– This index evaluates how well an item predicts the criterion it is intended to measure. The three types of validity measures are-

- Content validity- ensures that the test items cover the full range of the construct being assessed.

- Criterion related validity- evaluates how well the test predicts or correlates with an external criterion related to the construct. This type of validity is divided into two subtypes- predictive validity, which measures how well the test forecasts future performance (like predicting academic success), and concurrent validity, which assesses the correlation between the test and other established measures taken at the same time.

- Construct validity- examines whether the test truly measures the theoretical construct it is intended to assess. This includes convergent validity, where the test should correlate with other measures of the same construct, and divergent validity, where it should not correlate with measures of different constructs.

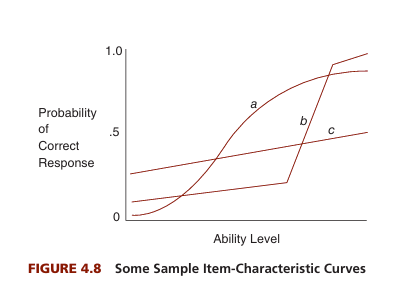

- Item-Characteristic Curve (ICC)– The ICC is a graphical representation of the probability of a correct response to an item as a function of the examinee’s level of the underlying trait. The curve helps identify how well an item performs across different levels of the trait being measured.

ICC- B indicates a scale with good items.

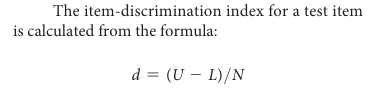

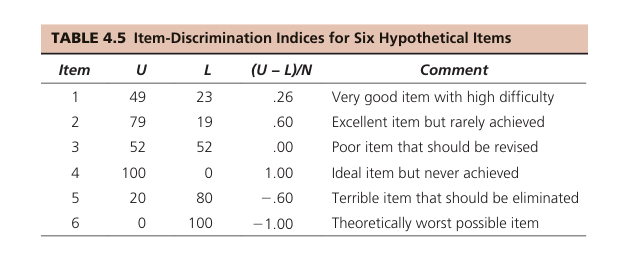

- Item-Discrimination Index- This index measures how well an item differentiates between high and low scorers on the test. It is calculated by comparing the proportion of correct responses from the upper and lower scoring groups. Values range from -1.0 (negative discrimination, where more low scorers get the item right) to +1.0 (positive discrimination, where more high scorers get the item right). Items with positive indices are preferred, and those with negative or zero values may be revised or discarded.

6. Revising the Items

Based on the results from testing the items, revisions are often necessary to improve the test’s quality. This phase involves analysing feedback, refining items, and adjusting test parameters to enhance reliability and validity.

- Item Revision- Items that performed poorly during the preliminary try-out are revised or discarded. For instance, items with low discrimination indices might be reworded or replaced to better differentiate between high and low scorers. Items that were found to be ambiguous or confusing are clarified or rephrased.

- Test Structure Adjustment- Changes to the test structure may be required based on the feedback and analysis. This could include adjusting the number of items, changing the format, or altering the time limits. For example, if the test is found to be too lengthy or too short, adjustments are made to balance the test’s length and ensure it fits within the intended administration time.

- Pilot Testing- After making revisions, the test is often piloted again with a different sample to verify that the changes have improved the test’s performance. This secondary pilot testing helps confirm that the revised items and structure meet the desired criteria for reliability and validity.

- Expert Review- Involving experts in the field for a review of the revised test can provide valuable insights. Experts can assess the content validity and overall quality of the test based on their professional experience and knowledge.

7. Publishing the Test

The final step in test construction is publishing the test, which involves creating a comprehensive manual and making the test available to potential users.

- Test Manual Preparation- The test manual is an essential component of the published test. It provides detailed information on the test’s development, administration, scoring, and interpretation. The manual should include:

- Introduction- Background information about the test, its purpose, and its intended use.

- Test Book- The actual test items or questions, formatted according to the chosen scaling method.

- Answer Key- For tests with objective items, such as multiple-choice questions, an answer key is provided.

- Scoring Instructions- Detailed guidelines on how to score the test, including any formulas or algorithms used.

- Reliability and Validity Data- Information on the test’s reliability and validity, including data from pilot testing and item analysis.

- Norms- Normative data for interpreting scores, including age, grade, and demographic breakdowns (e.g., urban vs. rural, different cultural backgrounds).

- Distribution- The test is made available through appropriate channels, which might include online platforms, professional organizations, or academic publishers. For instance, standardized tests like the WAIS or SAT are distributed through educational and psychological testing agencies.

- Training and Support- Providing training and support for users is crucial for ensuring the proper administration and interpretation of the test. This might involve workshops, online tutorials, or user guides to help practitioners effectively use the test.

- Ongoing Evaluation- Even after publication, ongoing evaluation of the test is important. This involves collecting feedback from users, monitoring test performance, and making updates as needed. Continuous review ensures that the test remains relevant and effective in measuring the intended constructs.

Conclusion to Test Construction

Psychological test construction is a multifaceted process that involves careful planning and execution to ensure that the tests are both valid and reliable. By following the systematic steps of defining test objectives, selecting appropriate scaling methods, constructing and testing items, revising based on feedback, and finally publishing the test, developers can create effective assessment tools. Each stage, from conceptualization to distribution, contributes to the accuracy and usefulness of the test in measuring psychological traits and behaviours.

As Gregory (2023) emphasizes, attention to detail and adherence to methodological standards are crucial for developing tests that can provide meaningful and reliable insights into human psychology. The continuous evaluation and refinement of these tests further ensure their relevance and effectiveness in diverse contexts.

References to Test Construction

American Psychological Association (APA). (2023). APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org

Allen, M. J., & Yen, W. M. (1979). Introduction to Measurement Theory. Longman.

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (2009). Psychological Testing (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

DeVellis, R. F. (1991). Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Sage Publications.

Gregory, R. J. (2023). Psychological Testing: History, Principles, and Applications (9th ed.). Pearson.

Kaplan, R. M., & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2005). Psychological Testing: Principles, Applications, and Issues (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Singh, A. K. (2006). Tests, Measurements and Research Methods in Behavioural Sciences. Bharati Bhavan.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 15,175 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2022, December 11). Steps in Psychological Test Construction- Master the 7 Steps to Create Great Tests. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/steps-in-psychological-test-construction/

These are wonderful notes,

Keep up the hardwork👍

Thank You!!