What is Hope?

There are multiple theories of hope which define hope in different ways. Most popular theory of hope is Snyder’s hope theory. Broadly, hope is a fundamental construct in positive psychology, acting as a vital motivational state that significantly influences individuals’ ability to achieve their goals and navigate life’s challenges.

According to Snyder (1991), hope can be defined as the belief in a positive future coupled with the strategies to reach that future.

This dual aspect of hope, encompassing both the desired outcomes and the pathways to achieve them, has made it a central focus of research and practice in the field of psychology.

Definitions of Hope

Some diverse definitions of it include-

- According to Snyder (1994), it is a cognitive process that involves the belief in one’s ability to create pathways to achieve goals and the motivation to pursue those pathways. It encompasses three components: goals, pathways, and agency.

- According to Marcel (1940), ‘Hope is an existential attitude that expresses a trust in the future. It is not merely wishful thinking but a deep-seated belief that positive change is possible despite present difficulties.

- According to Dufault & Martocchio (1985), it is a multidimensional concept characterized by a positive outlook and the anticipation of favorable outcomes, often associated with resilience and coping strategies in the face of adversity.

- According to Cheavens et al. (2006), Hope is a cognitive and emotional resource that enhances individual health and well-being by fostering adaptive coping strategies and encouraging proactive behavior toward health goals.

- According to Goleman (1995), Hop is an essential emotional resource that contributes to personal development and psychological resilience, enabling individuals to envision and work toward a preferred future.

Childhood Antecedents of Hope

Snyder (1994) claim, hope has no hereditary contributions but rather is entirely a learned cognitive set about goal-directed thinking.

The teaching of pathways and agency goal-directed thinking is an inherent part of parenting, and the components of hopeful thought are in place by age 2 years.

Pathways thinking reflects basic cause-and-effect learning that the child acquires from caregivers and others. these pathways are acquired before agency thinking.

Agency thought reflects the baby’s increasing insights as to the fact that s/he is the causal force in many of the cause-and-effect sequences in his/her surrounding environment.

Neurobiological Bases for Hope

Snyder said Hope is learned mental set.

Hope is not merely mental states. They have electrochemical connections that playa large part in the workings of the

immune system and, indeed, in the entire economy of the total human organism (Cousins, 1991).

Pickering and Gray (1999), goal directed actions are regulated by the behavioral inhibition system (BIS) and the behavioral activation system (BAS). The BIS is thought to be responsive to punishment, and it signals the organism to stop, whereas the BAS is governed by rewards, and it sends the message to go forward. A related body of research suggests a behavioral facilitation system (BFS) that drives incentive-seeking actions of organisms (Depue, 1996).

Read More- Self-Determination Theory

Snyder’s Theory of Hope

Snyder’s Hope Theory, developed by psychologist Charles R. Snyder in the early 1990s, posits that Hope is a cognitive process that involves the belief in positive outcomes and the perceived capability to initiate and sustain actions toward achieving those outcomes. This theory has significant implications for understanding how it influences psychological well-being, resilience, and goal achievement.

Process of Hope

Core Components of Hope Theory

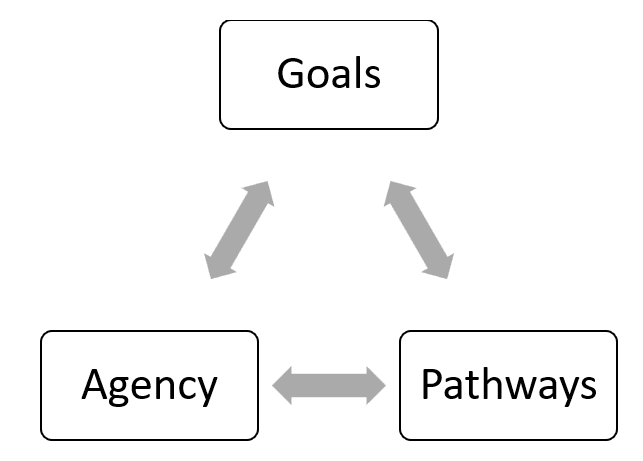

Snyder identified three primary components that collectively define the concept-

Components of Hope in Snyder’s Theory of Hope

Goals-

Goals are the desired outcomes or endpoints that individuals strive to achieve.

They can range from specific short-term objectives- few minutes /days (e.g., study for internal exam, completing a project) to long-term aspirations – months & years (e.g., pursuing a career, becoming a rich).

Goals can be approach oriented (e.g. aimed at reaching a desired goal) or preventative (aimed at stopping an undesired event) (Snyder, Feldman, Taylor, Schroeder, & Adams, 2000).

Goals can vary in relation to the difficulty of attainment, with some quite easy and others extremely difficult.

Goals provide direction and purpose, acting as a foundation upon which hopeful thinking is built. Individuals who have clear and meaningful goals are more likely to experience higher levels of hope (Snyder et al., 1991).

2. Pathways Thinking-

Pathways thinking has been shown to relate to the production of alternate routes when original ones are blocked (Snyder, Harris, et aI., 1991). To have positive self talk positive self-talk about finding routes to desired goals Snyder, LaPointe, Crowson, & Early, 1998).

For example ”I’ll find a way to solve this”.

Pathways refer to the perceived strategies or routes that individuals can take to achieve their goals.

This includes the ability to generate multiple solutions or alternatives when faced with obstacles. The capacity to identify various pathways is critical to maintaining hope.

When individuals encounter barriers, their ability to devise alternative routes is a key factor in their persistence and overall sense of hope (Snyder, 2000). Pathway thinking enables individuals to be flexible and adaptable in the pursuit of their goals.

3. Agency Thinking –

Agency is the belief in one’s ability to initiate and sustain actions toward goal achievement. It encompasses self-efficacy, motivation, and the willingness to take risks. they will endorse energetic personal self-talk statements (Snyder, LaPointe, et aI., 1998).

For example “I will keep going”

Agency reflects the personal conviction that one can affect change in their life and reach their goals. A strong sense of agency contributes to resilience, as hopeful individuals are more likely to take proactive steps to overcome challenges (Snyder et al., 1991).

The interplay between goals, pathways, and agency forms the basis of Snyder’s Hope Theory. These components are not isolated; rather, they work synergistically to create a hopeful mindset.

For instance, an individual may set a goal (e.g., to graduate from college), identify various pathways (e.g., study groups, tutoring, time management strategies), and believe in their ability to achieve this goal (agency). When one component is lacking, it may diminish. For example, if an individual cannot see a pathway to achieving their goal, their sense of hope may decrease.

High hopers have positive emotional sets and a sense of enthusiasm that stems from their past success in goal pursuits, whereas low hopers have negative emotional sets and a sense of emotional flatness that stems from their past failures in goal pursuits.

Read More- What is My Level of Happiness (Oxford Happiness Questionnaire)

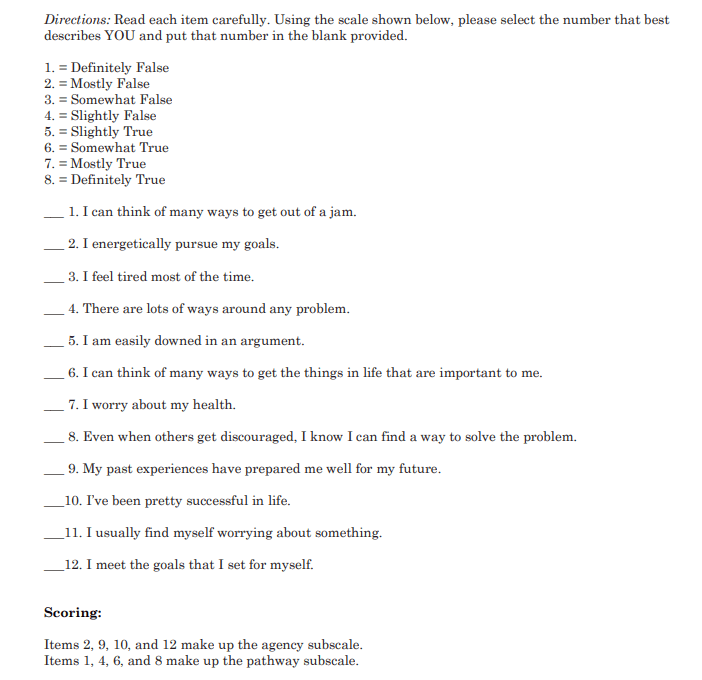

Hope Scale of Snyder

To measure the construct of hope quantitatively, Snyder developed the Hope Scale, a psychometric tool that assesses the levels of hope in individuals. The scale consists of items that evaluate the two main dimensions of it- agency and pathways. Respondents rate their agreement with various statements, providing insights into their hopeful outlook.

Hope Scale

Example Items-

- “I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are important to me.” (Pathways)

- “I am determined to make my goals happen.” (Agency)

The Hope Scale has been widely utilized in research and clinical settings, contributing to a deeper understanding of hope’s role in various psychological constructs, including well-being, resilience, and motivation (Snyder et al., 1991).

The Children’s Hope Scale (CHS)

Developed by Snyder, Hoza, et aI., (1997) is a six item self-report trait measure appropriate for children age 8 to 15.

Three item reflect agency thinking (e.g., “I think I am doing pretty well”), and three reflect pathways thinking (e.g., “When I have a problem, I can come up with lots of ways to solve it.”

Children respond to the items on a 6-point Likert continuum (1 = None of the time to 6 = All of the time).

The alphas have been close to .80 across several samples, and the test-retest reliabilities for I-month intervals have been. 70 to .80. The CHS has shown convergent validity in terms of its positive relationships with other indices of strengths (e.g., self-worth), and negative relationships with indices of problem (e.g., depression). Lastly, factor analyses have corroborated the two-factor structure of the CHS (Snyder, Hoza, et aI., 1997).

State Hope Scale (SHS)

Developed by Snyder and colleagues (Snyder, Sympson, et al., 1996)

Six-item self-report scale that taps here-and now goal-directed thinking.

Three items reflect pathways thinking-e.g., “There are lots of ways around any problem that I am facing now”-and

three items reflect agency thinking-”At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals.”

The response range is 1 = Definitely false to 8 = Definitely true.

Internal reliabilities are quite high (alphas often in the .90 range). Strong concurrent validity results also show that SHS scores correlate positively with state indices of self-esteem and positive affect and negatively with state indices of negative affect. Likewise, manipulation-based studies reveal that SHS scores increase or decrease according to situational successes or failures in goal-directed activities. Finally, factor analysis has supported the two-factor structure of the SHS (Snyder, Sympson, et aI., 1996)

Key Findings

Numerous studies have highlighted the benefits of hope in various contexts-

- Health- Higher levels of hope are associated with better physical health outcomes. For example, a study by Cheavens et al, (2006) found that individuals with higher hope levels demonstrated greater adherence to medical treatments and better overall health status. Moreover, it can act as a buffer against stress, contributing to lower levels of physiological arousal and improved immune function (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004).

- Academic Performance- Research indicates that students with higher hope levels tend to achieve better academic results. A study by Snyder et al, (2006) revealed that it positively correlated with academic performance, as hopeful students were more engaged and motivated in their studies.

- Workplace Success- In professional settings, hopeful employees are more productive, display greater job satisfaction, and are less likely to experience burnout. A study by Caza et al, (2012) found that it significantly predicted job satisfaction and organizational commitment among employees in various sectors.

- Cultural Perspectives- Cross-cultural studies have revealed varying levels of hope and its impact, influenced by cultural values and societal norms. For instance, a study by Chen et al, (2013) found that hope is experienced differently across cultures, with collectivist cultures placing greater emphasis on community goals, whereas individualistic cultures focus on personal aspirations.

Practical Exercises to Enhance Hope

To cultivate hope, individuals can engage in the following exercises-

Ways to Enhance Hope

- Goal Setting- Identify specific, achievable goals and outline multiple pathways to accomplish them. Use the SMART criteria (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) to create clear and actionable objectives (Doran, 1981).

- Reflect on Successes- Regularly reflect on past achievements to bolster confidence and a sense of agency. Journaling about successes can help individuals recognize their strengths and capabilities.

- Visualization Techniques- Visualize achieving your goals and the steps required to get there. This mental rehearsal can enhance motivation and belief in one’s abilities (Gregg et al., 2010).

- Social Support- Build a network of supportive relationships that encourage it. Engaging with others who share similar goals can provide motivation and create a sense of community.

- Positive Affirmations- Incorporate daily positive affirmations that reinforce hope and agency. Affirmations can enhance self-efficacy and promote a positive mindset (Friedman et al., 2014).

Conclusion

It is a vital aspect of positive psychology that significantly influences mental health, resilience, and overall life satisfaction. By fostering it through targeted interventions and practical exercises, individuals can enhance their well-being and achieve their aspirations. As research continues to explore the multifaceted nature of it, its importance in promoting psychological health and resilience becomes increasingly clear.

References

Caza, B. B., & Milton, L. P. (2012). Resilience at work: Building capability in the face of adversity. Organizational Dynamics, 41(2), 144-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2012.01.006

Cheavens, J. S., Feldman, D. B., Gum, A., Michael, S. T., & Snyder, C. R. (2006). Hope therapy in a community sample: A pilot investigation. Social Indicators Research, 77(1), 61-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5553-0

Chen, S., Farruggia, S. P., & Moss, S. A. (2013). The role of hope in academic and work environments: A focus on collectivist cultures. Cross-Cultural Research, 47(1), 31-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397112452653

Doran, G. T. (1981). There’s a SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35-36.

Dufault, K., & Martocchio, B. C. (1985). Hope: Its spheres and dimensions. Nursing Clinics of North America, 20(2), 379-391.

Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 745-774. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456

Friedman, R., & Zuckerman, E. (2014). The effect of positive affirmations on self-efficacy and achievement. Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(2), 119-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.776969

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bantam Books.

Gregg, M., Hosek, J., & Landau, J. (2010). Visualization: A means to enhance hope and goal attainment. Journal of Sport Psychology, 22(3), 203-214.

Marcel, G. (1940). Being and having. Harper & Row.

Snyder, C. R. (1991). The psychology of hope: You can get there from here. Free Press.

Snyder, C. R. (1994). The psychology of hope: Pathways to envisioning and realizing goals. In C. R. Snyder & D. R. Forsyth (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 257-267). Oxford University Press.

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570-585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

Snyder, C. R., Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Pulvers, K. M., Adams III, V. H., & Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and academic success in college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 820-826. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.820

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 13,984 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, December 12). Snyder’s Theory of Hope- 3 Components of Hope. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/snyders-theory-of-hope/