Introduction

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) was developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan in the 1980s as a comprehensive framework for understanding human motivation. Unlike behaviorist approaches that focus on external rewards or punishments, SDT asserts that humans are motivated by the fulfillment of three core psychological needs- Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness. SDT also makes a critical distinction between intrinsic motivation (driven by internal satisfaction) and extrinsic motivation (driven by external rewards).

Read More- Motivation

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

- Intrinsic Motivation– This refers to doing an activity for its inherent satisfaction rather than for some separable consequence. When people are intrinsically motivated, they engage in activities because they find them enjoyable or interesting. For example- A student who reads books on biology because they find the subject fascinating is intrinsically motivated.

- Extrinsic Motivation- This refers to doing an activity to attain a reward or avoid punishment. It can sometimes undermine intrinsic motivation if overemphasized, though it can be valuable for specific tasks. For example- A student who studies hard to win a scholarship is extrinsically motivated.

Deci and Ryan argue that over time, extrinsic motivators can become internalized. For example, if a student starts studying just to get good grades (extrinsic motivation), but gradually develops an interest in the subject, they might become intrinsically motivated.

In order to move from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation, three important psychological needs need to be fulfilled. Goals that aligh with the three needs are called Self-Concordant Goals.

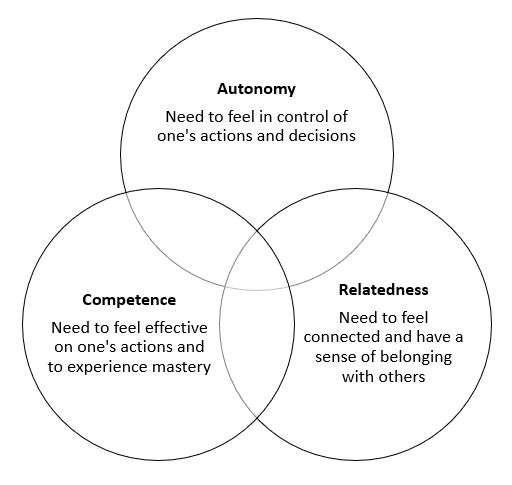

3 Psychological Needs

Three Psychological Needs

1.Autonomy

It refers to the need to feel in control of one’s actions and decisions. It is the desire to act with a sense of volition and choice, rather than feeling pressured or coerced by external forces.

For example- A student who chooses their own academic path, such as selecting their electives or participating in activities that align with their interests, feels more autonomous. This autonomy boosts their intrinsic motivation, leading them to engage more deeply in their studies.

2. Competence

Competence is the need to feel effective in one’s actions and to experience mastery. It involves a sense of confidence that one’s abilities and efforts can lead to success. Challenges that are neither too easy nor too difficult help foster a sense of competence.

For example- A student who works hard to solve a difficult math problem and eventually masters it experiences a sense of competence. Positive feedback from teachers or incremental successes further reinforce this feeling, motivating the student to continue improving.

3. Relatedness

Relatedness is the need to feel connected and have a sense of belonging with others. It involves developing meaningful relationships and being part of a supportive community.

For example- A student who forms strong friendships within a study group or feels supported by their teachers experiences relatedness. This sense of belonging helps them stay motivated and engaged in their studies, knowing that they are not isolated in their efforts.

Read More- Take a Quiz on Motivation

The Continuum of Motivation

Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci)

SDT outlines a continuum from amotivation (lack of motivation), to external regulation (pure extrinsic motivation), to identified regulation (where external motivators become more self-endorsed), and finally to intrinsic motivation.

For instance- A student who initially dislikes writing essays (amotivation) might begin working hard to meet teacher expectations (external regulation), and later, as they become more proficient, they might find joy in the creative process and become intrinsically motivated.

The Types of regulations included in the theory are-

Types of Regulations

- Amotivation- refers to a complete lack of motivation or intention to engage in a behavior. In this state, individuals feel either incompetent or perceive the behavior as irrelevant. They do not see a connection between their actions and the outcomes, leading to disengagement. There is non-regulation (absence of intentionality and motivation).

- External Regulation- External regulation is the most controlled form of motivation, where behavior is entirely driven by external rewards or punishments. The individual acts to obtain a tangible reward or to avoid a negative consequence. External locus of control (LOC), since the motivation stems from external pressures or rewards, and the individual is not acting out of personal interest.

- Introjected Regulation- With introjected regulation, individuals start to internalize external demands or pressures, but their behavior is still driven by a sense of obligation, guilt, or self-imposed pressure. The individual feels they “should” or “must” do something to avoid feeling bad about themselves, rather than truly wanting to do it. Somewhat external LOC, as the student’s actions are driven by internalized external pressures, not personal choice or values.

- Identified Regulation- At this stage, individuals recognize and accept the value of a goal or behavior, even if they do not find the activity inherently enjoyable. The motivation is more self-determined, as the person consciously identifies with the importance of the behavior in achieving desired outcomes.Somewhat internal LOC, as the student now values the behavior and recognizes its importance for their personal goals, even though external outcomes still play a role.

- Integrated Regulation- In integrated regulation, external motivations become fully integrated into an individual’s sense of self and personal values. The behavior is aligned with their identity and goals, making it entirely self-endorsed. Although the behavior is still motivated by outcomes, it feels more autonomous and authentic. Internal LOC, as the behavior is fully integrated into the student’s self-concept, making it driven by personal values and a sense of autonomy.

- Intrinsic Regulation- Intrinsic regulation is the most autonomous form of motivation, where the behavior is driven purely by internal satisfaction, enjoyment, or interest. The activity itself is the reward, and the individual engages in it because they find it inherently pleasurable or fulfilling. Entirely internal LOC, as the motivation comes from personal enjoyment and interest, with no need for external rewards or pressures.

Strengths of Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

- Focus on Psychological Well-Being- SDT emphasizes the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in promoting psychological well-being. Studies show that individuals whose psychological needs are met experience greater happiness, life satisfaction, and reduced anxiety (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

- Flexibility in Explaining Motivation- SDT provides a flexible framework that accounts for both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. It explains how individuals can internalize external motivators and move along the continuum toward more self-determined behavior (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

- Application to Diverse Domains- The theory is applicable across different life contexts, including education, work, sports, and personal growth. Its principles can help improve engagement and performance in various fields by emphasizing personal meaning and psychological fulfillment (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

- Promotion of Long-Term Motivation- SDT argues that fostering intrinsic motivation is more likely to result in long-term engagement and persistence in tasks, as opposed to extrinsic motivators, which may lead to burnout or disinterest when rewards are no longer available (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Weaknesses of Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

- Difficulty in Operationalizing the Continuum- While SDT provides a clear theoretical framework, measuring the precise transition between the different types of motivation (e.g., from external regulation to identified regulation) can be challenging in empirical research (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

- Cultural Limitations- SDT is rooted in Western individualistic values, particularly the emphasis on autonomy. In collectivist cultures, where the group or community may take precedence over individual choice, the focus on autonomy may not hold the same significance or motivational power (Chirkov et al., 2003).

- Potential Overemphasis on Intrinsic Motivation- While intrinsic motivation is valuable, extrinsic motivators like rewards, praise, or status are often necessary and beneficial in specific contexts. For example, extrinsic motivators can serve as the initial driver for behaviors that later become internally motivated, but SDT sometimes downplays their importance (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

- Limited Focus on Emotions- Although SDT addresses the emotional impact of motivation, it does not delve deeply into the complexities of emotions like fear, shame, or anxiety, which can also drive behavior (Deci & Ryan, 2000). This narrow focus may limit the theory’s ability to explain certain motivational dynamics in situations where emotions play a dominant role.

Research on SDT

- Increasing Intrinsic Motivation- Research highlights that positive feedback enhances learners’ confidence in their abilities, thereby promoting further engagement and intrinsic interest in tasks (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Providing choices in task completion fosters autonomy and motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). When individuals have the freedom to choose how they approach their tasks, they are more likely to feel a sense of ownership and intrinsic motivation.

- Weakning Intrinsic Motivation- Negative feedback and punishment decrease intrinsic motivation by undermining autonomy and increasing perceptions of external control (Lepper & Greene, 1978). Such external pressures can lead individuals to feel less motivated to engage in tasks that they otherwise might find enjoyable. Rewards perceived as controlling can diminish intrinsic motivation but may assist in transitioning from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation if they are seen as informative (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). Understanding how well they are performing can help individuals move along the motivation continuum.

- Childhood Influences- Children with supportive relationships exhibit greater intrinsic motivation (Cassidy, 1994). Secure attachments in childhood encourage exploration and curiosity, leading to higher levels of intrinsic motivation. A non-controlling approach from parents and teachers enhances intrinsic motivation by meeting needs for autonomy and competence (Grolnick & Ryan, 1989). Supportive educational and home environments foster students’ intrinsic interest in learning.

- Task Characteristics- Activities that are moderately challenging and provide a sense of accomplishment foster intrinsic motivation (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). When tasks are appropriately challenging, they encourage engagement and satisfaction, which are key components of intrinsic motivation.

- Self Efficacy- Self-efficacy plays a role; individuals are more motivated to engage in tasks they believe they can succeed in (Bandura, 1997). A strong belief in one’s capabilities enhances motivation and persistence in challenging tasks.

- Overall Satisfaction- Intrinsic motivation leads to personal satisfaction and emotional fulfillment, often linked to achieving personal standards and goals (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Engaging in intrinsically rewarding activities fosters positive emotions and overall well-being.

Conclusion

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Richard Ryan and Edward Deci, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding human motivation and well-being. By emphasizing the importance of intrinsic motivation and the fulfillment of three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—SDT highlights the conditions necessary for individuals to thrive both personally and in social contexts.

The evidence supporting SDT spans various domains, including education, health, sports, and personal relationships, indicating that when individuals pursue goals that resonate with their intrinsic motivations and align with their core psychological needs, they experience greater satisfaction, enhanced performance, and improved overall well-being. The theory underscores the need for environments that support autonomy and offer positive feedback, while also recognizing that punitive measures and controlling rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation.

Moreover, SDT illustrates the developmental aspects of motivation, showing that nurturing supportive relationships and environments during formative years can foster a lifelong sense of intrinsic motivation. By prioritizing strategies that cultivate autonomy, competence, and relatedness, educators, parents, and leaders can create conditions conducive to intrinsic motivation, ultimately leading to more fulfilling and productive lives.

Self-Determination Theory not only enhances our understanding of motivation but also serves as a guiding principle for fostering environments that promote psychological health, personal growth, and well-being across diverse contexts.

References

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Baumgardner, S. R., & Crothers, M. K. (2009). Positive psychology. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

Carr, A. (2011). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion Regulation: Influences of Attachment Relationships. In N. A. Fox (Ed.), The Development of Emotion Regulation: Biological and Behavioral Considerations (pp. 228-249). Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum.

Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parenting Styles and Autonomy Support: Why They Matter. Children and Youth Services Review, 11(3), 165-172.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112.

Lepper, M. R., & Greene, D. (1978). Turning Play into Work: Effects of Adult Surveillance and Extrinsic Rewards on Children’s Intrinsic Motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(1), 129-137.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141-166.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 16,503 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, October 23). Self-Determination Theory and 3 Psychological Needs. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/self-determination-theory/