What is Resilience?

Resilience involves achieving positive outcomes despite facing significant life challenges or adversities. These challenges can derail normal development or disrupt healthy functioning.

Masten (2001) defined resilience as a class of phenomena characterized by good outcomes in spite of serious threats to adaptation or development.

Ryff & Singer (2003) emphasize resilience as the maintenance, recovery, or improvement in mental or physical health following challenge.

According to Masten two components that are required for an behvaiour to be classified as resilience includes-

1. Facing Significant Risk- Resilience cannot be assessed unless a person faces a substantial risk or threat. Examples of such threats include growing up in abusive homes, parental mental illness, alcoholism, or poverty. These conditions put individuals at risk for developmental or psychological problems.

2. Positive Outcomes- For resilience to be judged, a person must show favorable outcomes despite risks. These outcomes may be measured against societal or developmental standards (e.g., academic achievement, mental health, or absence of negative behaviors).

Judgement of Resilience

Resilient responses occur throughout life, including childhood and adulthood. Common life challenges include raising children, job loss, illness, divorce, relocation, and physical decline in older age. Masten (2001) calls this resilience “ordinary magic” as it is a normal part of human development.

The foundations of resilience include psychological resources such as a flexible self-concept that allows adaptation to change, a strong sense of autonomy and self-direction, and the ability to master one’s environment, along with social resources like supportive, intimate relationships that provide emotional backing and social security.

Read More- Positive Emotions

Developmental vs. Clinical Perspectives

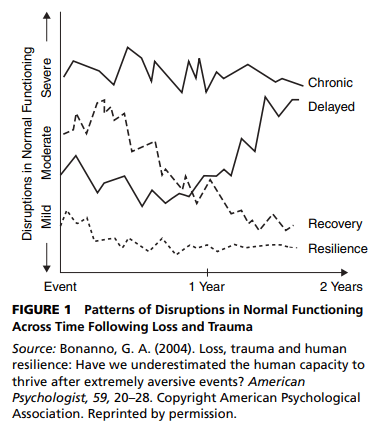

According to Bonanno (2004), there are four distinct patterns of response to trauma:

- Chronic Response- This pattern involves a prolonged period of disruption in functioning, where the individual experiences ongoing distress, without significant improvement over time, indicating long-term psychological or emotional difficulties.

- Delayed Response- In this case, the person initially seems to cope well or remain stable following a traumatic event, but later experiences a significant onset of distress or dysfunction, manifesting after an initial period of apparent resilience.

- Recovery- This pattern is marked by an intense, immediate reaction to trauma, such as severe emotional distress or clinical symptoms (e.g., depression or post-traumatic stress), followed by a slow and gradual return to the individual’s pre-trauma levels of functioning, which can take months or even years.

- Resilience- Characterized by a brief period of disruption or distress immediately following the trauma, this pattern involves a rapid recovery and return to stable, healthy functioning, with minimal long-term impact on the individual’s overall mental health.

Changes After Trauma

1. Developmental Perspectives of Resilience

Research has investigated a variety of factors that may threaten normal development. Studies show that children who grow up in physically abusive homes, who have parents suffering from mental illness or alcoholism, or raised in poverty are at significant risk for a variety of problems.

Compared to children raised by healthy parents, for example, children raised by parents with mental illnesses are at greater risk for developing mental illnesses themselves.

The second part of resilience requires judgment of a favorable or good outcome. However, the standards for judging outcomes defined by the relating expectations of society for the age and situation of the individual. Orphanage children compared to “normal” adopted and non-adopted children for purposes of evaluating deficits and delays in development.

Some researchers have also defined resilience as an absence of problem behaviors or psychopathology following adversity. Children of alcoholic, mentally ill, or abusive parents may be resilient. If they don’t develop substance abuse problems, suffer mental illness, become abusive parents themselves, or show symptoms of poor adjustment.

Resilient responses to adversity are common across the life span. Raising kids, divorce, relocation, job loss, illness, loss of a significant other, and physical declines late in life are all common parts of the human experience. Social resources are also important to resilience. Including quality relationships with others who provide intimacy and social support.

2. Clinical Perspectives of Resilience

Developmental researchers have examined children who faced adversity during some part of their growing up years. Resilient responses documented by the fact that some children showed healthy outcomes despite facing serious threats to normal development. Clinical investigations have examined how people cope with more specific life challenges occurring within a shorter frame of time.

In clinical psychology has investigated shorter-term reactions to specific events, such as loss (e.g., death of a loved one) and trauma (i.e., violent or life-threatening situations).

Bonanno (2004) describes a resilient response to a specific loss or trauma as, “The ability of adults in otherwise normal circumstances who are exposed to an isolated and potentially disruptive event, such as a death of a close relation or a violent or life-threatening situation, to maintain relatively stable, healthy levels of psychological and physical functioning”.

Bonanno argues that recovery, judged by mental health criteria, involves a period of clinically significant symptoms (e.g., of posttraumatic stress or depression) lasting at least 6 months. This period followed by a much longer time frame of several years, during which the individual gradually returns to the level of mental health that existed before the trauma or loss. Resilience, on the other hand, involves short-term disturbances in a person’s normal functioning lasting only for a period of weeks.

Resilience characterized by “bouncing back” from negative experiences. within a relatively short period of time. The concept of resilience highlights the strength of the individual and his or her coping resources.

Recovery begins with more severe reactions and takes considerably more time before the person returns pre-event levels of functioning. The concept of recovery highlights individual vulnerability and coping resources that have been overwhelmed. Bonanno argues for a greater awareness that resilience is both a common and a healthy response to loss and trauma.

Sources of Resilience in Children

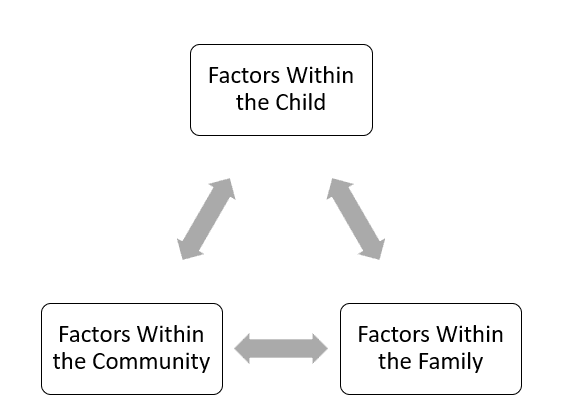

According to Ann Masten (2001), resilience in children arises from a variety of protective factors that exist within the child, family, and community. These factors, often referred to as “ordinary magic,” help children cope with adversity-

Factors / Sources of Resilience in Children

- Protective Factors within the Child

- Good intellectual and problem-solving abilities- Children who can think critically and solve problems tend to adapt better to challenges.

- Easy-going temperament and adaptable personality- Flexibility and emotional stability help children manage stress.

- Positive self-image and personal effectiveness- Confidence in their abilities encourages children to overcome obstacles.

- Optimistic outlook- Children with hope for the future are more resilient.

- Ability to regulate emotions and impulses- Emotional control helps prevent negative responses to stress.

- Valued individual talents- Talents appreciated by the child and their culture contribute to self-worth.

- Sense of humor- A healthy sense of humor can provide emotional relief in difficult situations.

- Protective Factors within the Family

- Close relationships with parents or caregivers- Secure attachments foster emotional resilience.

- Warm and supportive parenting- Clear expectations, along with emotional warmth, create a nurturing environment.

- Emotionally positive family environment- Minimal conflict between parents helps children feel safe and secure.

- Structured home environment- Consistent routines provide stability.

- Parental involvement in education- Active engagement in learning fosters a child’s sense of competence.

- Adequate financial resources- Families with fewer financial struggles can provide a more stable environment.

- Protective Factors within the Community

- Good schools- High-quality education promotes intellectual growth.

- Social organization involvement- Participation in school or community groups provides social support.

- Caring, involved neighborhood- A safe, supportive community fosters resilience.

- Access to health and social services- Timely assistance from competent professionals helps manage crises effectively.

Sources of Resilience in Adults and Later Life

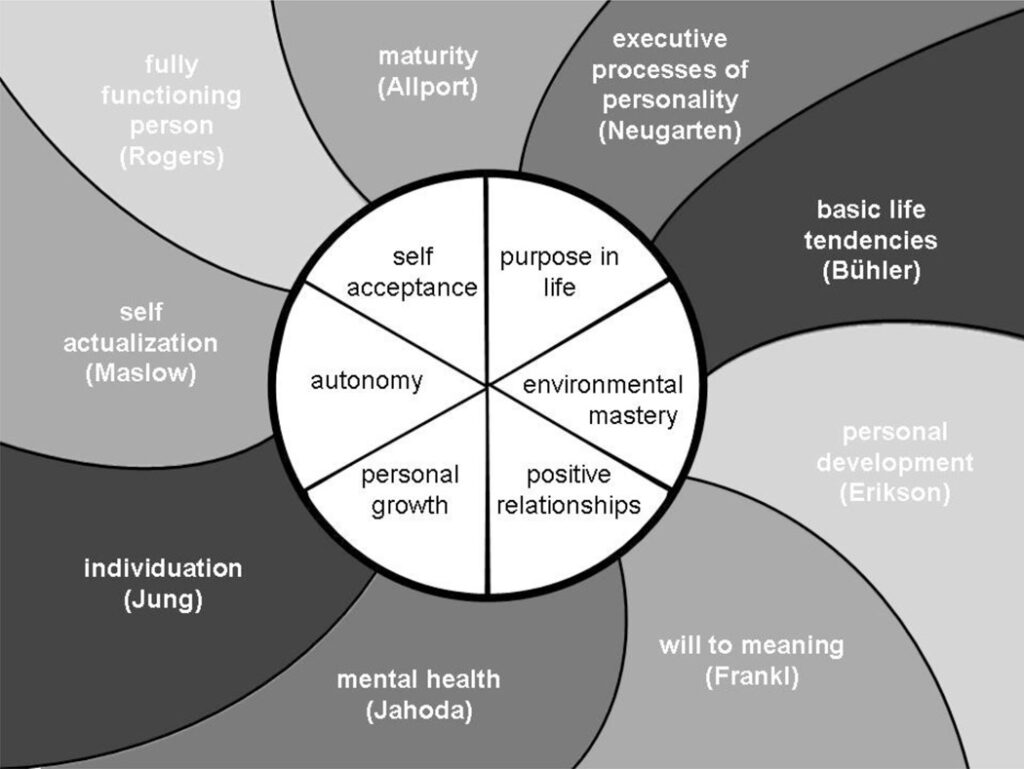

In adulthood, many of the same factors that build resilience in children continue to be important, with the addition of personal development and relational resources. Carol Ryff’s six dimensions of psychological well-being are key to resilience in adults, helping them cope with adversity and maintain mental health-

Ryff’s Theory

- Self-Acceptance- Resilient adults possess a positive attitude toward themselves, accepting both strengths and weaknesses, which allows for a stable self-concept even in difficult times.

- Personal Growth- A sense of ongoing development and openness to new experiences promotes a resilient mindset, as individuals see challenges as opportunities for learning.

- Purpose in Life- Having clear goals and a sense of meaning gives adults a reason to persevere through hardship, often motivated by work, religion, or helping others.

- Environmental Mastery- Resilient adults demonstrate competence in managing the demands of their environment, whether through work, family, or finances, contributing to a sense of control over their lives.

- Autonomy- A strong sense of independence and the ability to resist negative social pressures help adults maintain their course in the face of challenges.

- Positive Relations with Others- Meaningful and trusting relationships provide emotional and practical support, which is crucial in coping with stress and adversity.

Both children and adults benefit from these internal and external protective systems, with resilience emerging not from extraordinary capabilities, but from ordinary, everyday factors that help individuals maintain balance and move forward after adversity.

Resilience Among Disadvantaged Youth

Poverty increases risks of emotional disorders, drug use, school failure, juvenile delinquency, and exposure to violence and crime (McLoyd, 1998; Steinberg et al., 1992). Despite being exposed to various risks, many children in poverty do not engage in criminal behavior, school failure, or emotional disorders. Protective factors, such as a stable and caring family, contribute to resilience (Masten, 2001; Myers, 2000b).

The study by Buckner, Mezzacappa, and Beardslee (2003) examined resilience in 155 youths (ages 8-17) and their mothers, focusing on families facing extreme poverty, with many experiencing homelessness. The sample included a diverse demographic: 35% Caucasian, 21% African American, 36% Puerto Rican Latino, and 8% other Latino.

Findings-

- Resilient Group- 29% (45 children) had no significant mental health issues and showed positive functioning across measures.

- Non-Resilient Group- 45% (70 children) showed significant mental health problems and deficits in functioning.

- Mixed Group- 26% (40 children) exhibited characteristics between the resilient and non-resilient groups.

Factors Differentiating Resilient and Non-Resilient Youths

- Exposure to Negative Life Events- Non-resilient children experienced more severe negative life events (e.g., abuse, death of a friend, parental arrests, illness). Non-resilient youths dealt with higher levels of chronic stress, including hunger, lack of safety, and daily challenges of poverty.

- Intellectual Competence- Resilient children had higher cognitive abilities which aided academic success and problem-solving, crucial in coping with poverty.

- Self-Esteem- Resilient children displayed higher levels of self-esteem, helping maintain a positive self-image despite the hardships.

- Self-Regulation Skills- Self-regulation was the most powerful predictor of resilience.

- Cognitive Self-Regulation- Involves planning, organizing, staying focused on tasks, and being flexible in solving problems.

- Emotional Self-Regulation- Ability to control emotions, suppress anger, and handle challenging social situations. It is linked to social competence and maintaining positive relationships.

These skills help youths stay goal-directed, manage stress, and avoid emotional outbursts.

High levels of supervision by mothers (knowing children’s whereabouts and companions) correlated with resilience. It created a sense of safety and value, contributing to the child’s self-regulation and emotional development.

Conclusion

Resilience, particularly among disadvantaged youth, highlights the remarkable ability of some individuals to thrive despite significant adversity. Research, such as the study by Buckner, Mezzacappa, and Beardslee (2003), underscores the importance of protective factors like self-regulation, intellectual competence, self-esteem, and parental monitoring in promoting resilience. While many children in poverty face high levels of stress and negative life events, those who develop strong self-regulation and have supportive environments are better equipped to overcome challenges. These findings emphasize that resilience is not just an innate trait, but one that can be cultivated through both personal and external resources, offering pathways to success even in the most difficult circumstances.

Reference

Baumgardner, S. R., & Crothers, M. K. (2009). Positive psychology. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Carr, A. (2011). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2022, April 28). Resilience- 2 Divergent Perspectives and Key Research. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/resilience/