Psychodynamic Perspective to Personality

Personality is a complex psychological construct that refers to the unique ways in which individuals think, act, and feel throughout life. It encompasses an individual’s consistent patterns of behavior, thoughts, emotions, and interpersonal interactions (Funder, 2016). Importantly, personality should not be confused with character or temperament, though they are integral parts of the overall personality. Character typically involves moral judgments about a person’s behavior, while temperament refers to biologically innate traits such as emotional reactivity and adaptability (Kagan, 2010).

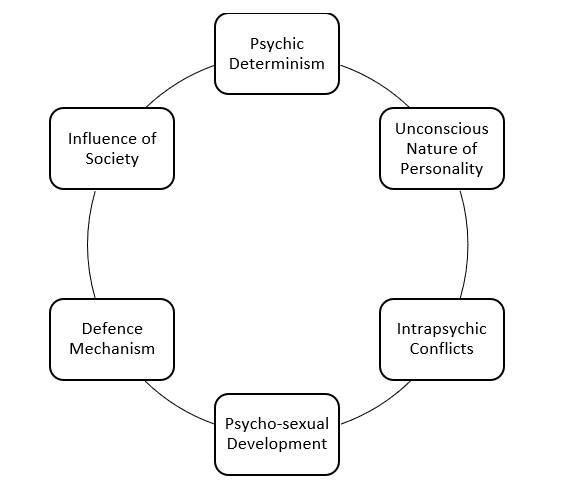

Throughout the history of psychology, various schools of thought have sought to explain how personality develops and influences behavior. Among these, the psychodynamic perspective, which originated with Sigmund Freud, offers a unique lens through which to view human behavior. The central tenets of this approach emphasize the role of unconscious processes, early childhood experiences, and the dynamic interaction between different parts of the psyche in shaping personality.

Psychodynamic perspective to personality

Psychodynamic Perspective to Human Nature

A core aspect of the psychodynamic perspective is its unique view of human nature. Freud and other psychodynamic theorists argue that human nature is largely shaped by unconscious forces that exist beneath the surface of conscious awareness. According to this view, human beings are driven by powerful instinctual impulses, many of which are irrational and rooted in primitive desires, such as the sexual and aggressive urges of the id. Freud’s rather pessimistic outlook on human nature suggests that individuals are often in conflict with themselves, struggling to reconcile their unconscious desires with societal expectations and moral standards.

Freud saw human behavior as motivated by the tension between biological instincts (primarily sexual and aggressive) and the demands of social life. This inner conflict, according to the psychodynamic perspective, is an inevitable part of the human experience, and it shapes not only personality but also mental health. Individuals must continually manage the demands of the id, ego, and superego, which can lead to psychological defenses, such as repression and denial, that protect the individual from overwhelming anxiety.

In contrast to Freud’s deterministic view of human nature, later psychodynamic theorists, such as Erik Erikson and Carl Jung, took a more optimistic approach. Erikson’s psychosocial theory suggests that individuals are not solely driven by biological urges but are also motivated by social and emotional factors. He believed that humans have the capacity for growth and change throughout the lifespan, and that overcoming the challenges of each psychosocial stage leads to the development of positive personality traits, such as trust, autonomy, and a sense of identity.

Carl Jung also presented a more positive perspective on human nature. He introduced the concept of self-realization—the idea that the ultimate goal of life is to achieve a state of wholeness by integrating all parts of the self, including the conscious, unconscious, and collective unconscious. Jung believed that humans are innately driven towards growth, creativity, and a deeper understanding of themselves and the world.

Thus, while the classical Freudian view often portrays human nature as being dominated by irrational and conflict-ridden instincts, later psychodynamic perspectives emphasize personal growth, adaptation, and the pursuit of meaning. These more contemporary psychodynamic theories acknowledge the complexity of human nature, incorporating both the influence of unconscious drives and the potential for conscious development and self-actualization.

Freud’s Psychodynamic Theory

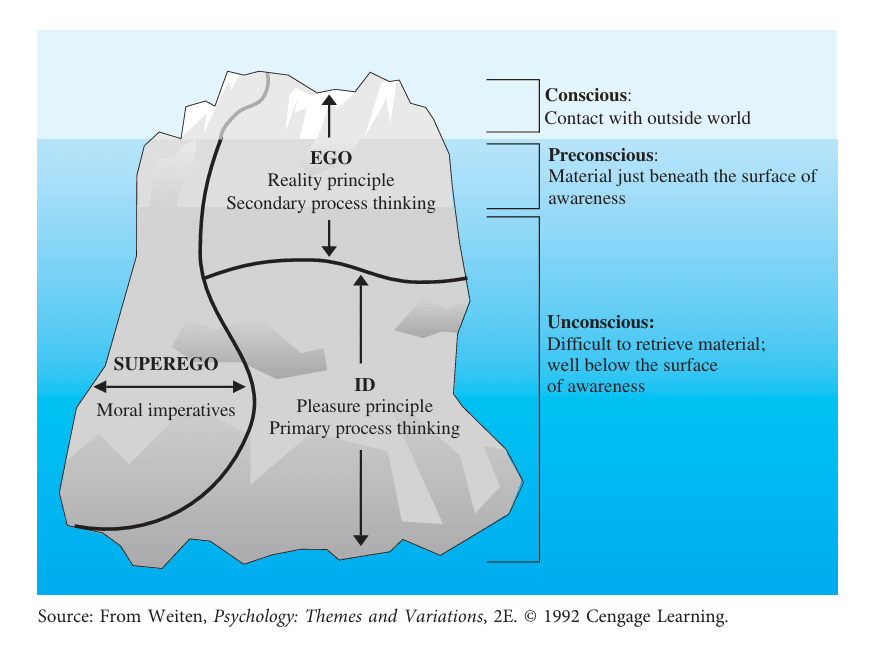

Sigmund Freud is perhaps the most well-known figure associated with the psychodynamic approach. Freud’s theory of personality development is deeply intertwined with his broader psychoanalytic framework, which emphasizes the unconscious mind as a crucial determinant of behavior. According to Freud, the human mind is divided into three levels of consciousness: the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious (Freud, 1900).

- The Conscious Mind– The conscious mind includes everything we are aware of at a given moment, such as thoughts, perceptions, and feelings.

- The Preconscious Mind– This part of the mind contains information that is not currently in awareness but can easily be accessed when needed. It includes memories and knowledge that can be retrieved from long-term storage.

- The Unconscious Mind– Freud’s most controversial contribution was his theory of the unconscious. He argued that much of our behavior is driven by desires, fears, and memories buried deep in the unconscious mind, which are inaccessible to conscious thought. These unconscious drives, primarily rooted in childhood experiences, exert a powerful influence over behavior, often surfacing in dreams, slips of the tongue, and other symbolic actions.

Freud’s model of the psyche also includes three key components that work in dynamic interaction with one another- the id, ego, and superego. The id represents the primal, instinctual drives for pleasure (particularly sexual and aggressive urges). The ego acts as the rational mediator, attempting to satisfy the id’s desires within the bounds of reality and social norms. The superego, on the other hand, represents internalized moral standards and ideals acquired from parents and society.

Psychosexual Stages of Development

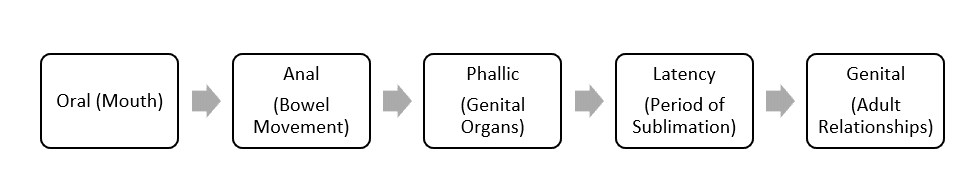

One of Freud’s most influential and controversial theories concerns the psychosexual stages of development. Freud believed that personality development occurs through a series of stages, each characterized by a focus on different erogenous zones. The stages include the oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital stages (Freud, 1905). According to Freud, unresolved conflicts or fixations during any of these stages can lead to specific personality traits or psychological disorders in adulthood. For instance, an individual fixated at the oral stage might develop habits such as smoking or overeating, which symbolize an unresolved need for oral stimulation.

Psychosexual Stages of Development

While Freud’s psychosexual stages have been criticized for their focus on sexual drives and the deterministic view of childhood experiences, his broader contributions to personality psychology continue to be influential. In particular, his emphasis on early childhood as a critical period for personality formation has shaped the work of many subsequent theorists (Eysenck, 2012).

Critiques and Developments of the Psychodynamic Perspective

Over time, Freud’s theories have faced substantial criticism. One major critique is that Freud overemphasized sexual motivations, particularly in the psychosexual stages, and portrayed them as central to personality development (Hoffman, 2013). Additionally, Freud’s ideas have been criticized for being unfalsifiable, making them difficult to test empirically using scientific methods (Popper, 2002). Despite these criticisms, Freud’s emphasis on unconscious processes and early experiences has remained a cornerstone of psychodynamic theory.

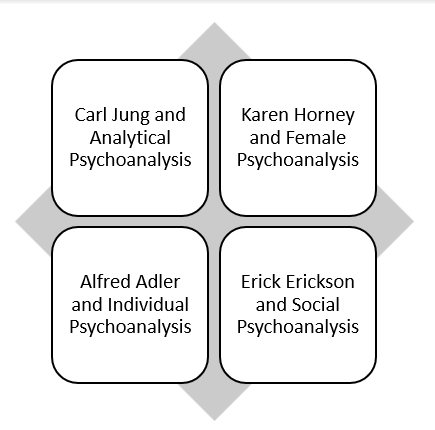

In response to the limitations of Freudian theory, several of Freud’s followers and contemporaries modified and expanded upon his ideas. This has led to the development of neo-Freudian approaches, which retain some of Freud’s insights while placing less emphasis on sexual motivations and more on social and interpersonal factors.

Neo-Freudians

Neo-Freudians

Carl Jung’ Analytical Psychoanalysis

One of the key figures in the development of modern psychodynamic theory is Carl Jung. Jung was originally a close collaborator of Freud but eventually broke away from Freud’s emphasis on sexuality. Jung developed his own theory, which placed greater emphasis on the collective unconscious—a shared reservoir of memories and archetypes common to all humans (Jung, 1969). According to Jung, these archetypes (such as the hero, the mother, and the shadow) influence human behavior and personality in profound ways, often through dreams and myths. Read more

2. Alfred Adler Individual Psychoanalysis

Another important neo-Freudian theorist was Alfred Adler, who disagreed with Freud’s focus on unconscious conflict and sexual drives. Instead, Adler emphasized the role of social interest and the striving for superiority as central motivations in personality development. He introduced the concept of the “inferiority complex,” which refers to feelings of inadequacy that drive individuals to compensate by seeking personal achievement or power (Adler, 1956). Read more

3. Erik Erikson’s Social Analysis

Erik Erikson, another influential neo-Freudian, extended Freud’s stages of development to include the entire lifespan. His psychosocial theory posits that personality develops through eight stages, each characterized by a central conflict that must be resolved for healthy development. Unlike Freud’s focus on early childhood, Erikson believed that personality continues to evolve throughout life, with each stage marked by challenges related to social and identity development (Erikson, 1950).

4. Karen Horney Female Psychoanalysis

As a Neo-Freudian, Karen Horney maintained many of the foundational ideas of Sigmund Freud but diverged significantly in her emphasis on social and cultural influences over biological factors in shaping personality. While Freud focused on innate drives, Horney argued that childhood experiences, particularly social relationships, were central to the development of neuroses. She criticized Freud’s notion of penis envy, proposing instead that feelings of inferiority in women stem from societal oppression, not biological destiny. Horney also introduced the concept of basic anxiety, stemming from childhood insecurity, and identified various neurotic coping strategies—moving toward, against, or away from others. Her work expanded psychoanalysis by integrating social and cultural dimensions into the understanding of personality development.

Modern Psychodynamic Approach

In modern iterations, the psychodynamic perspective has shifted away from Freud’s original focus on sexual drives and unconscious conflict. Instead, contemporary psychodynamic theories place a greater emphasis on the development of the self and interpersonal relationships. For instance, object relations theory—a major branch of modern psychodynamic theory—focuses on the internalized representations of important figures (or “objects”) in a person’s life and how these influence their sense of self and interactions with others (Klein, 1948).

Attachment theory, initially developed by John Bowlby, is another extension of psychodynamic thought. Bowlby’s work on the attachment bond between infants and their primary caregivers has led to a greater understanding of how early attachment experiences shape adult personality and interpersonal relationships (Bowlby, 1969). Research on attachment styles (secure, anxious, avoidant) has demonstrated that these early patterns of attachment can have long-lasting effects on emotional regulation, relationships, and even mental health (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

Applications of Psychodynamic Theory

Despite its origins in the early 20th century, the psychodynamic perspective continues to be relevant in clinical practice today. Many therapists still draw upon psychodynamic principles in their work with clients, though the approach has evolved to incorporate more contemporary understandings of human behavior. One area where psychodynamic theory remains influential is in the treatment of complex and deep-rooted psychological issues such as trauma, depression, and personality disorders.

Psychodynamic therapy, which stems from Freud’s original psychoanalytic approach, is a form of talk therapy that focuses on exploring unconscious patterns of thought and behavior. However, modern psychodynamic therapy is typically shorter-term and less intensive than traditional psychoanalysis. It aims to help individuals gain insight into their unconscious motivations and how these influence their current relationships and behavior (Shedler, 2010).

For example, research suggests that psychodynamic therapy can be particularly effective for treating personality disorders, as it helps individuals develop a better understanding of their internal conflicts and how these manifest in maladaptive patterns of thinking and behaving (Leichsenring & Rabung, 2008). Additionally, psychodynamic principles have been integrated into newer therapeutic approaches, such as mentalization-based therapy (MBT), which is used to treat borderline personality disorder by helping clients understand and regulate their emotions (Fonagy et al., 2002).

Future Directions

Although the psychodynamic perspective has evolved considerably since Freud’s time, there are ongoing debates about its scientific validity and practical applications. One of the key criticisms of psychodynamic theory is its reliance on subjective interpretations of unconscious processes, which can be difficult to measure or verify empirically (Westen, 1998). Additionally, some researchers argue that psychodynamic therapy is less effective than cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or other evidence-based approaches for treating certain mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders (Hofmann et al., 2012).

Despite these criticisms, proponents of the psychodynamic approach argue that it offers unique insights into the complexities of human personality, particularly in areas such as unconscious motivation, emotional development, and interpersonal dynamics. As research in neuroscience and psychology continues to advance, there may be opportunities to integrate psychodynamic principles with other theoretical frameworks, such as cognitive psychology and neuroscience, to develop a more comprehensive understanding of personality (Solms, 2018).

Conclusion

The psychodynamic perspective, originating with Freud, remains a foundational approach to understanding personality development and behavior. While Freud’s emphasis on sexual drives and unconscious conflict has been critiqued and refined over time, the core principles of psychodynamic theory—such as the role of unconscious processes and early experiences—continue to shape modern psychology. Contemporary developments, including- Object relations theory, attachment theory, and psychodynamic therapy, reflect the enduring relevance of this approach in both research and clinical practice. As our understanding of the human mind evolves, the psychodynamic perspective will likely continue to provide valuable insights into the complexities of personality.

References

Adler, A. (1956). The individual psychology of Alfred Adler: A systematic presentation in selections from his writings. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. Norton.

Eysenck, H. J. (2012). The biological basis of personality. Transaction Publishers.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. Karnac Books.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. Macmillan.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Basic Books.

Funder, D. C. (2016). The personality puzzle (7th ed.). W. W. Norton.

Hoffman, I. Z. (2013). Ritual and spontaneity in the psychoanalytic process: A dialectical-constructivist view. Routledge.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Kagan, J. (2010). The temperamental thread: How genes, culture, time, and luck make us who we are. Dana Press.

Klein, M. (1948). Contributions to psychoanalysis, 1921-1945. Hogarth.

Leichsenring, F., & Rabung, S. (2008). Effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 300(13), 1551-1565.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press.

Popper, K. (2002). The logic of scientific discovery. Routledge.

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65(2), 98-109.

Solms, M. (2018). The neurobiology of the free energy principle: An interview with Karl Friston. Neuropsychoanalysis, 20(1), 67-75.

Westen, D. (1998). The scientific status of unconscious processes: Is Freud really dead? Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 46(4), 1061-1106.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 15,423 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2022, February 23). Introduction Psychodynamic Perspective to Personality- Discover the 4 Insightful Neo-Freudians. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/psychodynamic-perspective-to-personality/