Introduction to Problem-Solving Cycle

Problem-solving is a critical cognitive process that individuals engage in regularly, whether in personal, academic, or professional situations. The ability to effectively identify, analyze, and solve problems is a key skill valued in various disciplines, from education to business.

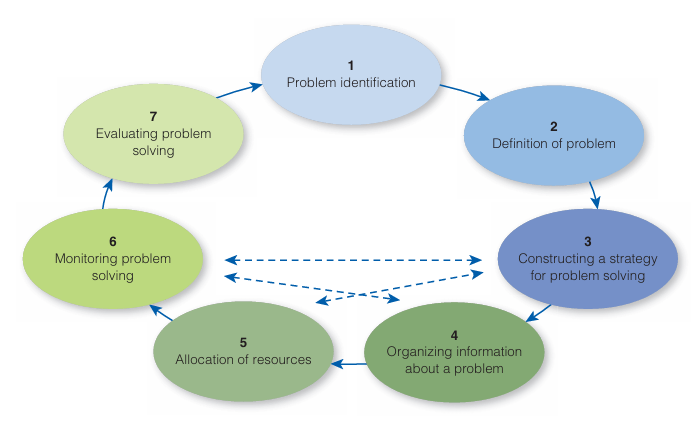

One way to approach problem-solving systematically is through the problem-solving cycle, a structured method consisting of several essential steps: problem identification, problem definition and representation, strategy formulation, organization of information, resource allocation, monitoring, and evaluation. These stages help guide individuals from recognizing the existence of a problem to finding and implementing a solution.

Each step in the problem-solving cycle plays a pivotal role, and the overall success of the process often hinges on how well these stages are executed. For instance, problem identification ensures that we recognize a situation as a problem in the first place, while problem definition helps in accurately understanding what the problem is. If a problem is poorly defined, the subsequent steps, such as strategy formulation or resource allocation, may lead to ineffective or inadequate solutions. Additionally, failure to properly monitor or evaluate progress can result in missed opportunities to detect errors or improve the solution.

By following the problem-solving cycle, individuals can work through complex issues more effectively and systematically. This approach not only encourages careful planning and analysis but also supports adaptability, as the process may involve revisiting and revising earlier steps as new information emerges. Through examples and evidence, the importance of each stage in the problem-solving cycle can be highlighted, showing how structured problem-solving leads to better outcomes across various domains.

Problem-Solving Cycle (Sternberg & Sternberg)

Problem Identification

The first stage in the problem-solving cycle is problem identification—recognizing that a problem exists. This step is critical because if a problem is not correctly identified, it cannot be resolved. Problems often stem from discrepancies between the current state and a desired state. Sometimes problems are obvious, such as a broken computer or an underperforming employee, but at other times, they may be more subtle, such as a gradual decline in customer satisfaction or personal motivation.

For example- Consider a marketing team in a small business. Over time, the company’s sales have been declining, but no one in the organization has identified this as a significant problem. Instead, they attribute it to seasonal changes, assuming that sales will pick up in a few months. Only when a member of the team decides to dig into the data and compares current sales figures to historical trends does the issue become apparent—there is a larger, more persistent drop in sales that warrants attention. In this case, the first stage of the problem-solving cycle, problem identification, only occurs when someone recognizes the existence of a deeper issue.

Research in cognitive psychology suggests that perceptual errors can prevent individuals from identifying problems, particularly when they rely on biased assumptions or fail to actively monitor for discrepancies (Heider, 1958). In organizational settings, a lack of feedback mechanisms can also hinder problem identification. Studies show that companies with strong feedback cultures are more likely to identify issues early and address them before they become significant problems (London & Smither, 2002).

2. Problem Definition and Representation

After identifying the problem, the next step is problem definition and representation. This involves clarifying what the problem is and how it is understood. Clear definition of the problem ensures that all stakeholders are aligned in their understanding of what needs to be resolved. This stage often requires breaking the problem down into smaller components and ensuring that the scope of the problem is neither too broad nor too narrow.

For example- Returning to the example of the marketing team, once the declining sales trend is identified, the next step is to define the problem more precisely. Is the decline related to product quality, marketing strategy, or changing consumer preferences? The team decides to analyze sales data by region, product, and customer demographic, discovering that the issue primarily lies with one underperforming product line that has not been updated in several years. By defining the problem more specifically, the team can focus their efforts on addressing the product line’s shortcomings, rather than wasting resources on unrelated issues.

Effective problem definition is supported by the Framing effect (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). How a problem is framed can significantly impact how individuals perceive and approach it. Studies show that problems framed in terms of potential losses are often approached more cautiously than those framed in terms of potential gains, which influences the chosen problem-solving strategies. In educational settings, students who clearly define a problem before attempting to solve it tend to perform better in problem-solving tasks (Pretz, Naples, & Sternberg, 2003). This finding emphasizes the importance of spending adequate time understanding the problem before moving forward.

Framing Effect

3. Strategy Formulation

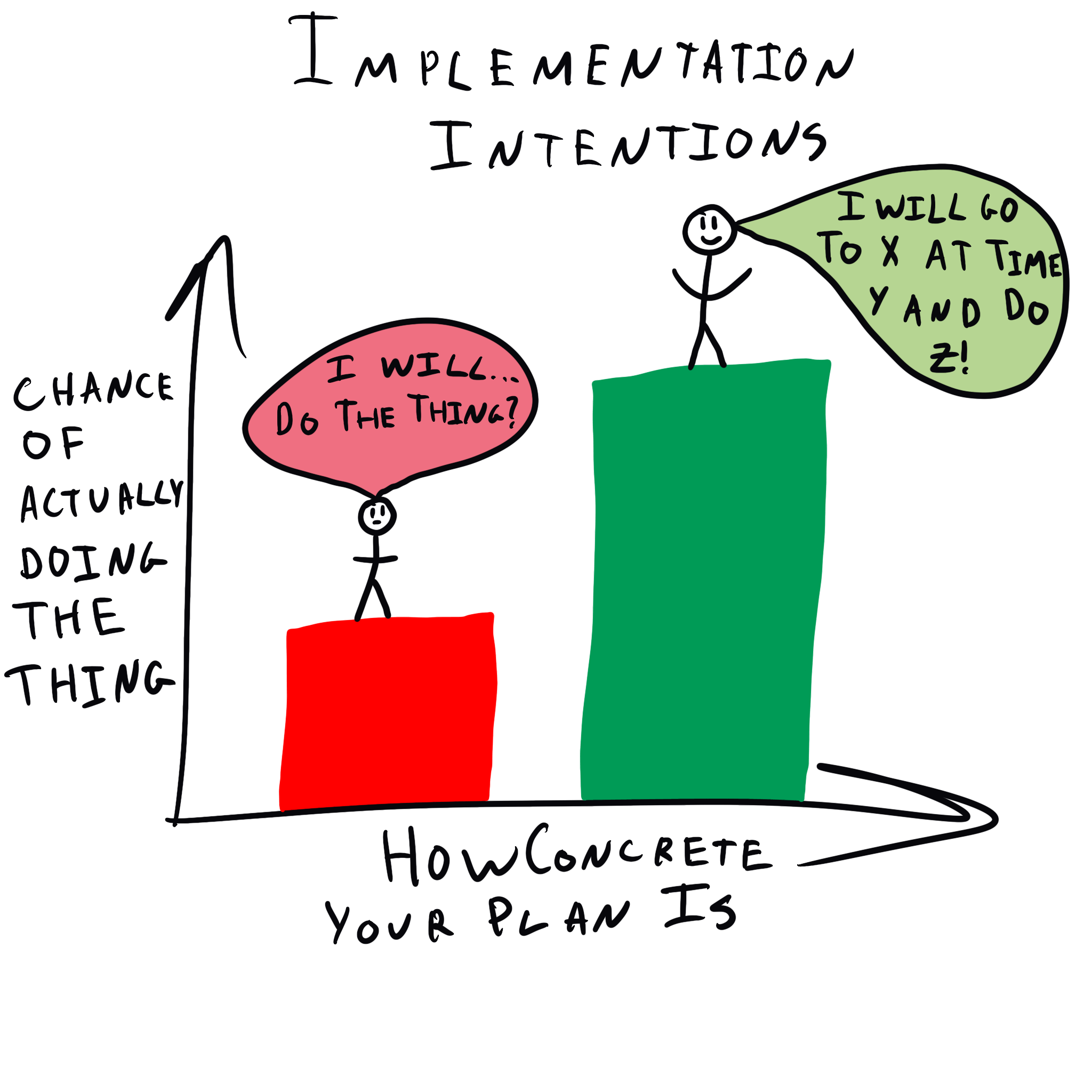

Once the problem is clearly defined, the next step is strategy formulation—deciding how to approach solving the problem. This involves selecting a plan based on the nature of the problem, available resources, and the desired outcome. Strategy formulation may involve analysis—breaking down the problem into smaller, more manageable parts—or synthesis, in which elements of the problem are combined in creative ways to generate new solutions.

Two key thinking processes are involved in strategy formulation- divergent thinking and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking involves brainstorming multiple possible solutions to a problem, while convergent thinking focuses on narrowing down those solutions to find the best one.

For example- For the marketing team, several strategies are proposed to solve the problem of declining sales in the underperforming product line. Some team members suggest a complete rebranding of the product, while others propose making incremental improvements based on customer feedback. To evaluate these options, the team engages in divergent thinking, generating as many creative ideas as possible. Once a range of solutions has been proposed, they shift to convergent thinking, narrowing down the options based on cost, feasibility, and projected impact on sales. Ultimately, they decide to update the product’s design and marketing strategy, focusing on a targeted ad campaign aimed at younger consumers.

Research on creative problem-solving highlights the importance of both divergent and convergent thinking (Guilford, 1967). Individuals who can generate a variety of solutions are more likely to find innovative ways to approach complex problems. However, without convergent thinking, it can be difficult to select the best course of action from the options available. Studies show that successful problem solvers often exhibit cognitive flexibility, the ability to switch between divergent and convergent thinking as needed (Mumford et al., 1991). This flexibility is essential for adapting strategies in response to changing circumstances.

4. Organization of Information

The fourth step in the problem-solving cycle is the organization of information. During this stage, individuals must determine how the various pieces of information related to the problem fit together. Organizing information involves structuring data in a way that highlights relationships between different elements of the problem, making it easier to discern patterns, connections, and potential solutions.

For example- The marketing team collects extensive information about consumer behavior, competitors, and past marketing campaigns. They organize this data by creating charts and visual representations to identify trends. For example, they use a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) to examine internal and external factors affecting their product line. This method allows them to see how different aspects of the problem are related and helps them identify key areas for improvement.

Research shows that organizing information is critical to problem-solving success. In one study, students who used graphic organizers to arrange information performed better on problem-solving tasks than those who did not (Hawk, McLeod, & Jonassen, 1993). Cognitive psychology also suggests that visualizing the structure of a problem can lead to insight, a sudden realization of a solution that emerges when the problem is viewed from a new perspective (Ohlsson, 1992). This “aha” moment often occurs when individuals reorganize information in a way that makes the solution more apparent.

5. Resource Allocation

Resource allocation refers to the distribution of time, effort, and other resources necessary for solving the problem. This step requires individuals to evaluate the costs and benefits of various approaches and decide how best to allocate their mental and physical resources.

For example- In the case of the marketing team, they must decide how much time and money to invest in addressing the decline in sales. They evaluate the cost of running an ad campaign, redesigning the product, and conducting further market research. Based on this analysis, they allocate a larger portion of their budget to the ad campaign, which they believe will have the most significant impact on sales. However, they also set aside time to monitor the campaign’s effectiveness and make adjustments if necessary.

Planning fallacy (The Decision Lab)

Research indicates that expert problem solvers allocate their resources differently from novices. Experts tend to spend more time on global planning, focusing on the big picture, while novices spend more time on local planning, focusing on smaller details (Larkin et al., 1980). For example, successful students spend more time deciding how to approach a problem before they begin working on it, which helps them avoid errors and false starts (Bloom & Broder, 1950). This finding underscores the importance of effective resource allocation in problem-solving.

6. Monitoring

As individuals work through the problem-solving process, they must continuously engage in monitoring to ensure that they are on track. Monitoring involves evaluating progress, identifying potential obstacles, and making adjustments as needed. This step is crucial because it helps individuals stay focused and avoid wasted effort.

For example- The marketing team monitors the performance of their ad campaign in real-time. They track key metrics such as click-through rates, engagement, and sales. After a few weeks, they notice that while the campaign is generating interest, it is not leading to significant sales increases. In response, they adjust their strategy by tweaking the ad copy and expanding the campaign to include a different demographic. This monitoring process helps them avoid spending more time and money on a strategy that is not working.

Monitoring is a form of metacognition, or thinking about one’s own thinking. Research shows that individuals who engage in metacognitive monitoring during problem-solving tasks are more successful than those who do not (Flavell, 1979). In one study, students who were trained to monitor their problem-solving strategies performed better on complex tasks than those who received no such training (Schraw & Dennison, 1994). Monitoring allows individuals to detect errors early and make adjustments before it is too late.

7. Evaluation

The final stage of the problem-solving cycle is evaluation—assessing whether the solution has been successful in solving the problem. This step involves reviewing the outcomes of the problem-solving process and determining whether any additional actions are necessary.

For example- After several months, the marketing team evaluates the overall impact of their efforts. They find that the updated product design and targeted ad campaign have successfully increased sales, but not to the level they had originally hoped. Based on this evaluation, they decide to implement additional changes to the product and continue refining their marketing strategy. By critically assessing the effectiveness of their solution, they ensure that they are constantly improving.

Research shows that individuals who engage in reflective practice—regularly evaluating their problem-solving processes—are more likely to achieve long-term success (Schön, 1983). In professional settings, organizations that conduct post-mortem analyses after completing projects tend to improve their problem-solving processes over time (Fong, 2006). Evaluation is essential for learning from past experiences and applying those lessons to future problems.

Conclusion to Problem-Solving Cycle

The problem-solving cycle offers a structured framework for tackling challenges in a methodical and effective way. This cycle comprises several key stages: problem identification, problem definition and representation, strategy formulation, organization of information, resource allocation, monitoring, and evaluation. Each step plays a pivotal role in ensuring that problems are approached systematically and resolved successfully. By following these stages, individuals and organizations can navigate complex issues more efficiently and achieve their desired outcomes.

Understanding and applying the principles of the problem-solving cycle is crucial for improving problem-solving capabilities. For instance, accurate problem identification helps in recognizing the presence of a problem, which sets the stage for the subsequent steps. Problem definition and representation refine the understanding of the issue, ensuring that strategies formulated are relevant and targeted. Effective strategy formulation involves devising practical solutions, while organization of information ensures that relevant data is structured coherently. Resource allocation optimizes the use of time, effort, and finances, while monitoring helps track progress and make necessary adjustments. Finally, evaluation assesses whether the solution is effective and identifies areas for further improvement.

The efficacy of the problem-solving cycle is well-supported by research across multiple disciplines, including cognitive psychology, education, and business. Studies have shown that systematic problem-solving approaches enhance cognitive abilities and lead to better outcomes. For example, research in cognitive psychology emphasizes the importance of clear thinking and strategic planning (Sternberg, 1986), while educational studies highlight how structured problem-solving improves learning and achievement (Schön, 1983).

In the business world, effective problem-solving processes are linked to improved organizational performance and innovation (Fong, 2006). By adhering to the steps of the problem-solving cycle, individuals and organizations can enhance their problem-solving skills, overcome challenges, and achieve lasting success.

Reference for Problem-Solving Cycle

Bloom, B. S., & Broder, L. J. (1950). Problem-solving processes of college students: An exploratory investigation. University of Chicago Press.

Carlson, M. P., & Bloom, I. (2005). The cyclic nature of problem solving: An emergent multidimensional problem-solving framework. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 58(1), 45-75.

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911.

Fong, G. (2006). Postmortem analysis and the improvement of project management. International Journal of Project Management, 24(1), 29-37.

Galotti, K. M. (2018). Cognitive psychology in and out of the laboratory. Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence. McGraw-Hill.

Hawk, P. P., McLeod, R. W., & Jonassen, D. H. (1993). Teaching and learning problem solving: Matching strategies with objectives. Educational Technology Research and Development, 41(1), 17-30.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2004). Managing emotions during team problem solving: Emotional intelligence and conflict resolution. Human Performance, 17(2), 195-218.

Larkin, J. H., McDermott, J., Simon, D. P., & Simon, H. A. (1980). Expert and novice performance in solving physics problems. Science, 208(4450), 1335-1342.

London, M., & Smither, J. W. (2002). Feedback orientation, feedback culture, and the longitudinal performance management process. Human Resource Management Review, 12(1), 81-100.

Matlin, M. W., & Farmer, A. (2019). Cognition (10th ed.). Wiley.

Mumford, M. D., Marks, M. A., Connelly, M. S., Zaccaro, S. J., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (1991). Cognitive and temperament predictors of creative problem-solving. Journal of Creative Behavior, 25(3), 256-278.

Ohlsson, S. (1992). Information-processing explanations of insight and related phenomena. Advances in Psychology, 93, 1-44.

Pretz, J. E., Naples, A. J., & Sternberg, R. J. (2003). Recognizing, defining, and representing problems. In J. E. Davidson & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of problem solving (pp. 3-30). Cambridge University Press.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460-475.

Schwarz, N., & Skurnik, I. (2003). Feeling and thinking: Implications for problem solving. In J. E. Davidson & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of problem solving (pp. 263-291). Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (1981). Intelligence and problem-solving. Cognition, 9(1), 45-59.

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). Intelligence applied: Understanding and increasing your intellectual skills. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Sternberg, R. J., & Sternberg, K. (2006). Cognitive psychology (p. 178). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453-458.

Zhou, J. (2013). Emotional intelligence and innovation performance. European Journal of Innovation Management, 16(1), 21-45.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 13,984 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, September 20). Problem-Solving Cycle- Discover Amazing 7 Steps to Solve Problems Insightfully. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/problem-solving-cycle-7-steps-to-solve-problems/

“Great post! It’s interesting to see how technology can both enhance and hinder our situational awareness. While tools like GPS and real-time data improve decision-making, they can also distract and disconnect us from our surroundings. A balanced approach is key!”