Introduction

Operant conditioning refers to the process by which the consequences of a behavior affect its likelihood of occurring again. The theory, largely developed by B.F. Skinner, emphasizes that behavior is shaped and maintained by reinforcement or punishment, making it a core mechanism in learning. Unlike respondent behavior, which is elicited by specific stimuli, operant behavior is spontaneous and occurs without a clear trigger. It becomes conditioned through interaction with the environment, responding to the consequences it produces.

Skinner’s experiments with the Skinner Box provide the basis for much of what we understand about operant conditioning today. This research highlights the significant impact of reinforcement and punishment on behavior, the shaping of actions through successive approximations, and the role of various reinforcement schedules in modifying behavior. Beyond laboratory experiments, Skinner’s theories have found application in real-world scenarios, influencing our understanding of personality, behavior modification, and self-control.

Read More- Learning

Respondent and Operant Behavior

Understanding operant conditioning begins with distinguishing between two types of behavior-

- Respondent behavior- refers to actions that are automatically elicited by specific stimuli, such as a reflexive response. For example, the classic Pavlovian response—a dog salivating at the sound of a bell after being conditioned to associate the bell with food—exemplifies respondent behavior. It is involuntary and tied directly to environmental triggers.

- Operant behavior- it is not elicited by a specific stimulus but is emitted voluntarily. These behaviors occur spontaneously and are reinforced or weakened by their consequences. A simple example is a child who spontaneously raises their hand in class and is praised by the teacher. The praise reinforces the behavior, making the child more likely to raise their hand in the future.

Read More– Classical Conditioning

Skinner Box

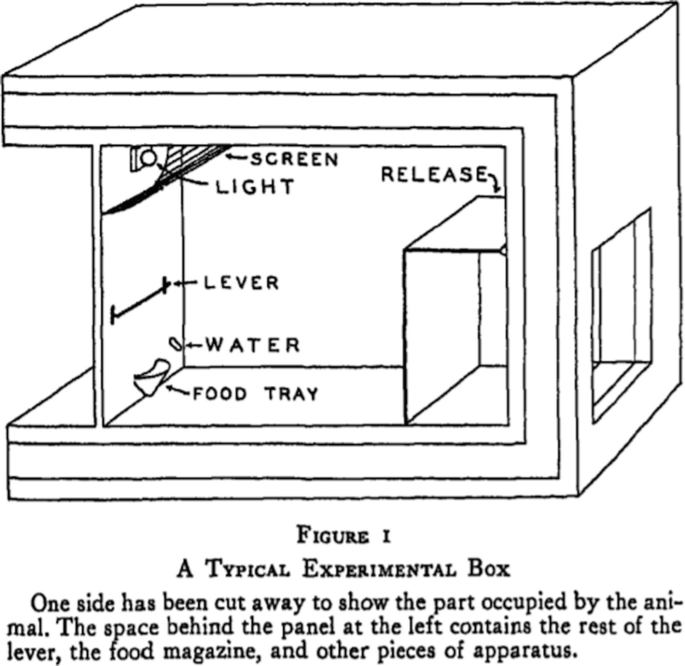

Skinner’s research on operant behavior was carried out primarily using the Skinner Box, a controlled environment where an animal, typically a rat or pigeon, could press a lever or peck a disk to receive a food pellet. This apparatus allowed Skinner to study the effects of reinforcement on behavior in a precise, measurable way. The animal’s spontaneous actions—such as pressing the lever—illustrate operant behavior, while the food pellet serves as the reinforcer, strengthening the likelihood of the behavior recurring.

Skinner Box

Initially, the rat’s behavior in the Skinner Box is random and exploratory. However, once the rat learns that pressing the lever produces food, its behavior changes. The animal starts pressing the lever more frequently, showing how reinforcement increases the rate of an operant behavior. If the food reinforcement is removed, the rat’s bar-pressing behavior decreases and eventually ceases—a process known as extinction. This extinction parallels the decline of respondent behaviors when reinforcement (or the stimulus associated with it) is withdrawn.

Types of Reinforcement and Punishments

In operant conditioning, reinforcement and punishment are key concepts used to shape behavior. While reinforcement increases the likelihood of a behavior recurring, punishment reduces the chances of a behavior being repeated. Both can be either positive or negative, and they play essential roles in behavioral psychology.

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is the process of encouraging or strengthening a particular behavior by following it with a consequence that makes the behavior more likely to happen in the future. There are two types of reinforcement-

- Positive Reinforcement- Positive reinforcement involves adding a pleasant stimulus after a behavior to increase the likelihood of that behavior being repeated. It is commonly used in various settings, such as education, the workplace, and even everyday interactions. For example- a teacher praises a student for answering a question correctly in class. The praise (a positive reinforcer) makes the student more likely to participate in future class discussions, as they associate answering questions with receiving praise.

- Negative Reinforcement- Negative reinforcement strengthens a behavior by removing an unpleasant or aversive stimulus when the desired behavior occurs. It’s often misunderstood, as “negative” here refers to the removal of a stimulus rather than something bad. For example- When you have a headache, you take aspirin, which removes the pain. The removal of the pain (the aversive stimulus) encourages you to take aspirin the next time you have a headache.

Punishment

Punishment is the process of decreasing or weakening a behavior by introducing a consequence immediately after the behavior. Like reinforcement, punishment can be either positive or negative, depending on whether something is added or removed.

- Positive Punishment- Positive punishment involves adding an unpleasant stimulus after a behavior to reduce the likelihood of that behavior recurring. In this context, “positive” means that something is introduced or added, but the goal is to discourage the behavior. For example- If a child misbehaves, and a parent scolds them, the scolding serves as positive punishment. The unpleasant experience of being scolded makes it less likely that the child will engage in the same misbehavior in the future.

- Negative Punishment- Negative punishment involves removing a pleasant stimulus after an undesirable behavior to decrease the likelihood of that behavior happening again. In this case, something enjoyable or rewarding is taken away. For example- If a teenager stays out past curfew, their parents might take away their car privileges for a week. The removal of the car (a desirable stimulus) serves as negative punishment, reducing the likelihood that the teenager will break curfew again.

Operent Conditioning in Human Behaviour

The principles observed in the Skinner Box extend beyond laboratory settings and into the real world. Skinner argued that all organisms, including humans, continuously engage in operant behaviors, constantly interacting with and responding to their environments. As a child learns to talk, walk, and socialize, their behaviors are shaped by reinforcement—praise, attention, or other rewards from caregivers and peers. Actions that yield positive consequences are repeated, while those that result in punishment or lack of reward diminish.

Through this lens, Skinner viewed personality as a collection of operant behaviors shaped by reinforcement over time. For instance, a child who is consistently rewarded for being polite or studious will likely develop those traits as part of their personality, while a child who is punished for aggressive behavior will be less likely to exhibit those traits.

Punishment vs Negative Reinforcement

While reinforcement strengthens behavior, punishment weakens it. Skinner distinguished between punishment—introducing an aversive stimulus to decrease behavior—and negative reinforcement, which strengthens behavior by removing an unpleasant stimulus. For example, taking aspirin to relieve a headache is negative reinforcement because it removes discomfort. In contrast, grounding a child for misbehavior is punishment because it introduces a negative consequence intended to reduce the behavior.

Although punishment can be effective, Skinner argued that it is less reliable than reinforcement for long-term behavior change. Overuse of punishment can lead to negative side effects such as fear, anxiety, and aggression.

Schedules of Reinforcement

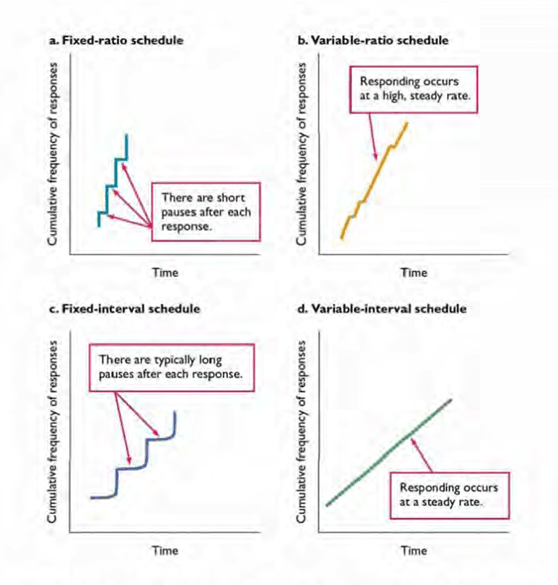

One of Skinner’s most influential contributions to psychology is his research on schedules of reinforcement. In everyday life, behaviors are not always reinforced continuously; reinforcement may be intermittent, occurring at varying intervals or ratios. Skinner identified several reinforcement schedules that influence the frequency and strength of a behavior-

- Fixed Interval- In this schedule, reinforcement is delivered after a set period, regardless of how many responses occur. For example, a paycheck received every two weeks regardless of daily performance exemplifies a fixed-interval schedule. Behavior tends to increase as the reinforcement time approaches but diminishes after the reward is given.

- Fixed Ratio- Here, reinforcement occurs after a specific number of responses. For example, a factory worker may be paid after producing a certain number of items. This schedule generally produces a high and steady rate of behavior, as more responses lead directly to more rewards.

- Variable Interval- Reinforcement is provided after varying intervals of time, which are unpredictable to the individual. A classic example is fishing, where catching a fish may happen after various time intervals of waiting. This schedule leads to consistent and steady behavior because the individual never knows when the reward will come.

- Variable Ratio- Reinforcement occurs after an unpredictable number of responses. Gambling, particularly slot machines, is a well-known example of this schedule, as the player never knows when the next reward will appear. This schedule generates high levels of persistent behavior and is very resistant to extinction.

Outcomes of Different Schedules of Reinforcement

Schedules of Reinforcement

Shaping

Shaping is a critical concept in operant conditioning, involving the gradual molding of behavior through successive approximations. Rather than waiting for an organism to exhibit the desired behavior spontaneously, an experimenter (or parent, teacher, etc.) reinforces small steps that lead toward the target behavior. Each closer approximation to the desired behavior is reinforced, while previous approximations are no longer rewarded.

For example- teaching a child to tie their shoes may begin by reinforcing the child for picking up the laces, then for making a loop, and finally for successfully tying the knot. This method allows complex behaviors to be learned incrementally.

Skinner demonstrated that even behaviors seemingly unrelated to an outcome could be shaped into complex actions through reinforcement. He famously shaped pigeons to perform intricate tasks, such as playing ping-pong, using successive approximations.

Case Analysis- Superstitious Behavior

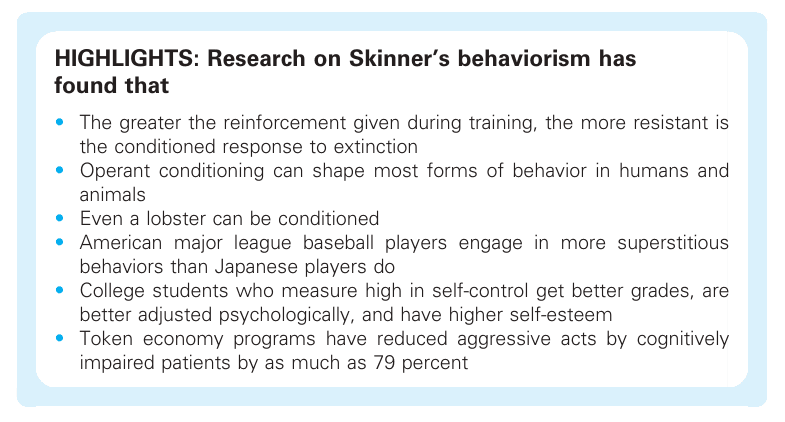

Superstitious behavior is an unintended consequence of operant conditioning. It occurs when an individual mistakenly associates a random or irrelevant action with a reinforcement. For instance, a pigeon may believe that turning in circles leads to food if it happens to turn just before receiving a food pellet. Even though the behavior and reward are unrelated, the behavior persists because the pigeon mistakenly believes it controls the outcome.

In humans, similar superstitions arise when people associate certain behaviors with unrelated events, such as wearing a “lucky” shirt to help their team win. Skinner showed how easy it is to shape superstitious behavior through random reinforcement.

Case Analysis- Self-Control

Skinner extended his theory to include self-control, which involves managing one’s own behavior through the use of operant conditioning principles. He identified several strategies for self-control, including-

- Stimulus Avoidance- Removing oneself from situations that trigger undesirable behaviors. For example, someone trying to quit smoking might avoid social gatherings where others are smoking.

- Self-Administered Satiation- Engaging in a behavior to the point of overindulgence to reduce its appeal. For instance, someone attempting to quit eating sweets might deliberately eat a large amount in one sitting to make the food less desirable.

- Aversive Stimulation- Using unpleasant stimuli to discourage unwanted behavior. For example, snapping a rubber band on the wrist whenever a craving for cigarettes arises.

- Self-Reinforcement- Rewarding oneself for displaying desired behaviors. A student might treat themselves to a movie after completing a difficult assignment as a form of self-reinforcement.

Applications of Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning has found extensive application in real-world settings through strategies like token economies and behavior modification programs. These techniques are grounded in the principles of reinforcement and punishment, which help shape behavior by rewarding positive actions and discouraging negative ones. These methods have been applied successfully in various settings, such as schools, prisons, hospitals, and rehabilitation centers, helping manage and improve behavior.

Token Economies

A token economy is a type of behavior management system where individuals earn tokens or symbolic rewards for engaging in specific desirable behaviors. These tokens, which have no intrinsic value on their own, can later be exchanged for meaningful rewards such as privileges, treats, or activities. This system is particularly effective because it uses positive reinforcement to encourage desired behaviors.

In a token economy, desirable behaviors are identified, and the individual is given tokens each time they perform one of these behaviors. The tokens can then be accumulated and traded for a larger reward. This system creates a structure where individuals are motivated to act in ways that are consistent with the program’s goals, as they are continually working towards receiving the reinforcers they value.

For example- in an educational setting, a teacher might implement a token economy to improve classroom behavior and academic performance. For example, students earn tokens for behaviors such as completing homework, participating in class, or following classroom rules. After collecting a certain number of tokens, students can exchange them for privileges like extra recess time, a homework pass, or a small prize. This strategy helps students internalize positive behaviors, as they are consistently rewarded for their efforts.

Behavior Modification Programs

Behavior modification programs, which are also based on operant conditioning principles, use reinforcement and punishment to alter specific behaviors. These programs are highly structured, and the key goal is to change undesirable behavior by increasing positive behavior and decreasing negative or harmful behavior. Behavior modification has been particularly effective in addressing issues such as aggression, impulsivity, and substance abuse.

For example- Children with ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) often struggle with impulsivity, hyperactivity, and inattentiveness, which can lead to disruptive behavior in school and home environments. A behavior modification program might be designed to encourage behaviors such as completing assignments, sitting still during class, or following instructions. For example, a child may be given a sticker or a token each time they complete a task without disruption. After collecting a certain number of stickers, the child might earn a larger reward, like extra playtime or a favorite activity.

Human Nature According to Skinner

Skinner’s theory raises significant questions about human nature and free will. His deterministic view suggests that behavior is largely controlled by external forces—reinforcers and punishers—rather than by internal motivations or conscious choice. This perspective has been controversial, with critics arguing that it diminishes the importance of cognitive processes and individual autonomy.

Nevertheless, Skinner’s research and ideas have had a profound impact on psychology, education, and behavioral therapy. His emphasis on observable behavior and measurable outcomes has made operant conditioning a cornerstone of behaviorist psychology, though it has been supplemented by later theories that account for cognition and emotion.

Research on Skinner’s Ideas

Criticism to the Approach

Critics have raised concerns about the limitations of the theory in explaining human behavior, its mechanistic view of human nature, ethical issues related to behavior control, and its neglect of internal processes such as thoughts and emotions. Some of the major criticisms of Skinner’s theory are-

- Overemphasis on External Behavior- Operant conditioning operates on the principle that behavior is shaped solely by reinforcement and punishment, but critics argue that this presents an incomplete picture of human psychology. Cognitive processes, such as decision-making, problem-solving, and emotional regulation, play a significant role in shaping behavior, and Skinner’s theory does not adequately account for these factors.

- Reductionist Approach- Skinner’s theory is often criticized for being overly reductionist, meaning that it reduces complex human behaviors to simple stimulus-response patterns. Critics argue that human behavior is more nuanced and cannot be fully explained by environmental factors alone. This reductionist view disregards other influences such as biological, genetic, social, and cultural factors, which also play crucial roles in shaping behavior.

- Ethical Concerns About Behavior Control- Another criticism of Skinner’s theory is its potential for unethical applications, particularly in its emphasis on controlling and manipulating behavior. Skinner believed that behavior could be shaped and controlled by manipulating the environment, which has raised ethical concerns about the use of operant conditioning in real-world settings, such as schools, prisons, and hospitals.

- Neglect of Free Will and Human Agency- Skinner’s theory suggests that behavior is entirely determined by environmental factors and reinforcement history, leaving little room for the concepts of free will or human agency. This deterministic view implies that individuals have no control over their actions, as behavior is a product of reinforcement contingencies. Many critics find this aspect of Skinner’s theory troubling because it undermines the idea of personal responsibility and the human capacity for self-determination.

- Limited Application to Complex Human Behaviors- While operant conditioning has been effective in shaping simple behaviors, such as teaching animals tricks or helping individuals develop good habits, critics argue that it is less successful when applied to more complex or abstract behaviors, such as creativity, critical thinking, or moral reasoning.

- Difficulty in Explaining Emotional and Social Behaviors- Skinner’s operant conditioning theory also struggles to explain emotional and social behaviors, which are often more complex and less directly tied to reinforcement contingencies. Emotions like love, empathy, and guilt, as well as social behaviors like cooperation and altruism, are difficult to address through the lens of operant conditioning.

Conclusion

B.F. Skinner’s operant conditioning theory has profoundly influenced our understanding of behavior and learning. From the basic principles of respondent and operant behaviors to the shaping of complex actions through reinforcement, Skinner demonstrated how behavior could be molded by consequences. His research on reinforcement schedules, shaping, superstitious behavior, and self-control continues to guide applications in therapy, education, and beyond.

Though his views on human nature remain controversial, the practical insights derived from his work ensure that operant conditioning remains a critical framework for understanding and modifying behavior.

References

Schultz, D.P., & Schultz, S.E. (2016). Theories of Personality (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Skinner, B.F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. Macmillan.

Skinner, B.F. (1974). About Behaviorism. Vintage Books.

Staddon, J.E.R., & Cerutti, D.T. (2003). Operant Conditioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 115–144.

Ferster, C.B., & Skinner, B.F. (1957). Schedules of Reinforcement. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Feldman, R. S. (2017). Understanding psychology (13th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 16,594 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2022, March 31). Operant Conditioning- Discover 4 Insightful Schedules of Reinforcement. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/operant-conditioning/