Introduction to Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory

George Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory (PCT) represents an important contribution to the field of psychology. It is emphasizing the active role of individuals in interpreting and anticipating their world. At its core, PCT views individuals as “scientists,” continuously testing and revising personal hypotheses about reality to adapt and thrive (Kelly, 1955).

Unlike other theories that frame behavior as determined by past experiences or unconscious motives, Kelly proposed that people actively construct their reality, with personal constructs acting as the lenses through which they view and predict events.

Read More- Personality

Personal Construct Theory

Personal Construct Theory departs from traditional deterministic views of psychology. Kelly argued that reality is not passively received; instead, individuals engage in a dynamic process of organizing and interpreting their experiences (Kelly, 1955).

Personal constructs, which are bipolar dimensions such as “happy-sad” or “successful-unsuccessful,” shape this interpretation. These constructs serve as the framework for predicting and understanding life events, enabling individuals to navigate their environment with greater efficacy.

Basic Assumptions of Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory

Some basic assumptions of the theory include-

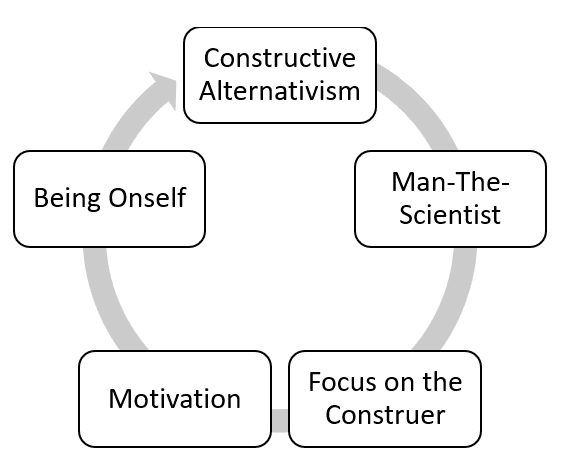

Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory- basic assumptions

- Constructive Alternativism- it is the philosophical foundation of George Kelly’s theory. It posits that reality is not an absolute truth but rather a subjective construction that can be interpreted and reconstructed in various ways (Kelly, 1955). Individuals are not constrained by a single, fixed interpretation of events. Instead, they have the capacity to reinterpret their experiences, which allows for flexibility and personal growth. This assumption emphasizes human agency and adaptability. It encourages individuals to adopt alternative perspectives when their current constructs no longer serve them effectively (Neimeyer, 1995).

- Man-the-Scientist- Kelly conceptualized individuals as “scientists” who actively observe their environment, formulate hypotheses (constructs), and test these through their experiences (Kelly, 1955). The “man-the-scientist” metaphor underscores human proactivity and rationality in engaging with the world. It suggests that people are not passive recipients of experience but active participants in shaping their understanding (Walker & Winter, 2007).

- Focus on the Construer- Kelly emphasized that the meaning of events lies not in the events themselves but in how individuals construe or interpret them (Kelly, 1955). This focus on the construer aligns with constructivist approaches in psychology, which prioritize the subjective experiences of individuals over universal laws or norms (Neimeyer & Neimeyer, 2002).

- Motivation- Kelly’s theory rejects the need for external drives or forces to explain human behavior, arguing that motivation is inherent in the process of construing (Kelly, 1955). This view shifts the focus from external motivators (e.g., biological drives, rewards, or punishments) to intrinsic cognitive processes. Motivation arises from the natural human tendency to predict, control, and adapt to their environment (Walker & Winter, 2007).

- Being Oneself- In PCT, “being oneself” involves consistency between one’s personal construct system and one’s actions, while also being open to revising constructs when needed (Kelly, 1955). This assumption highlights the balance between maintaining a coherent sense of self and embracing change when constructs fail to accommodate new experiences.

11 Corollaries Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory

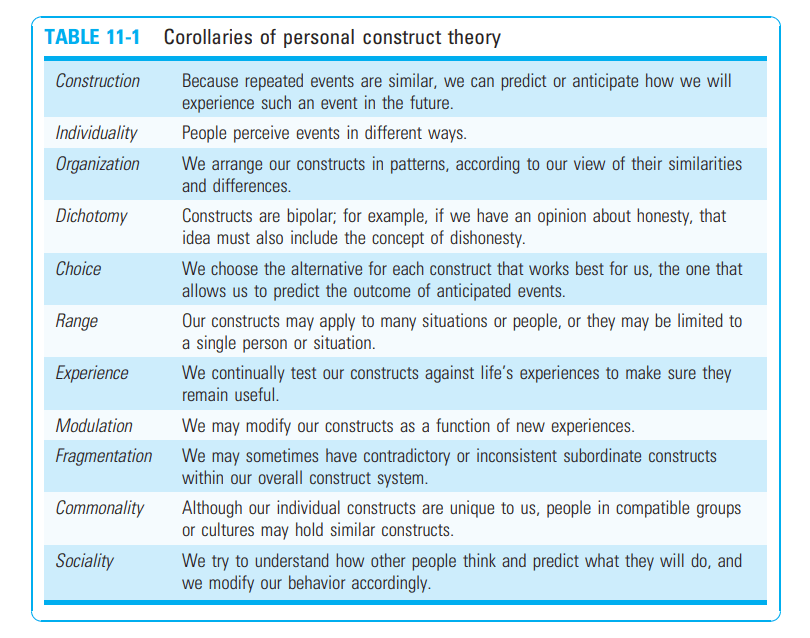

Kelly proposed eleven corollaries that provide a detailed framework for understanding how constructs function and evolve. These corollaries highlight the interplay between individual differences, social interactions, and the adaptability of constructs.

Kelly’s personal construct theory is presented fundamental postulate – “our psychological processes are directed by the ways in which we anticipate events.” The word processes means that personality was a continually

flowing, moving process. Our psychological processes are directed by our constructs, by the way each of us construes our world. Kelly’s notion of constructs is anticipatory. We use constructs to predict the future so that we have some idea of the consequences of our actions, of what is likely to occur if we behave in a certain way.

11 Corollaries- Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory

1. Construction Corollary-

It states that individuals anticipate future events by construing their replications (Kelly, 1955). In other words, people use past experiences to predict future occurrences.

For instance, someone who observes that hard work leads to success may construct the belief that persistence is key to achieving goals.

2. Individuality Corollary-

It asserts that people differ in how they construe events (Kelly, 1955). These differences arise from unique life experiences, cultural backgrounds, and personal perspectives.

For example, two individuals witnessing the same event may interpret it differently based on their existing constructs.

3. Organization Corollary-

It posits that personal constructs are hierarchically organized, with broader, overarching constructs guiding more specific ones (Kelly, 1955). This organization facilitates the efficient processing of information.

For instance, an overarching construct such as “trustworthy” may encompass more specific constructs like “honest,” “reliable,” and “loyal.”

4. Dichotomy Corollary-

It highlights the bipolar nature of constructs, which consist of opposing elements (e.g., kind-cruel, fair-unfair) (Kelly, 1955). This dichotomy helps individuals categorize and interpret experiences.

5. Choice Corollary-

It suggests that individuals choose between constructs that maximize their ability to predict future events (Kelly, 1955). This choice often involves a trade-off between security (maintaining existing constructs) and growth (adopting new ones).

For instance, a person may choose to reinterpret a challenging experience as an opportunity for growth rather than a failure, thereby fostering resilience.

6. Range Corollary-

It posits that each construct has a limited range of applicability (Kelly, 1955). Constructs are not universal; they are relevant only within specific contexts.

For example, a construct like “friendly-unfriendly” may be applicable to social interactions but not to inanimate objects. This specificity allows constructs to remain relevant and focused.

7. Experience Corollary-

It emphasizes that constructs evolve through new experiences (Kelly, 1955). As individuals encounter novel situations, they must modify their constructs to accommodate these changes. This process of adaptation fosters learning and personal development.

8. Modulation Corollary-

It suggests that the permeability of a construct determines its ability to accommodate new experiences (Kelly, 1955). For example, someone with a rigid “success-failure” construct may struggle to integrate alternative perspectives, whereas someone with a more flexible construct can adapt more readily.

9. Fragmentation Corollary-

It acknowledges that individuals may hold contradictory constructs in different contexts (Kelly, 1955). For instance, a person may perceive themselves as “confident” at work but “insecure” in social settings, demonstrating the context-dependent nature of constructs.

10. Commonality Corollary-

It posits that shared constructs among individuals lead to shared understandings (Kelly, 1955). For example, people with similar cultural backgrounds may develop similar constructs, fostering a sense of connection and mutual understanding.

Sociality Corollary- It emphasizes the importance of understanding another person’s construct system for effective social interactions (Kelly, 1955). Empathy, for instance, involves perceiving the world through another’s constructs. This corollary underscores the relational aspect of construct theory, where interpersonal understanding enhances collaboration and connection

Kelly’s Perspective on Human Nature

Kelly’s perspective on human nature can be understood using the following concepts-

- Free Will vs. Determinism- PCT aligns with the concept of free will, emphasizing individuals’ active role in constructing their reality. Unlike deterministic theories that attribute behavior to external factors, PCT suggests that people have the agency to reinterpret and adapt their constructs (Kelly, 1955).

- Nature vs. Nurture- While constructs are shaped by personal experiences (nurture), they also reflect innate tendencies to organize and predict (nature). Kelly’s theory bridges the gap between these perspectives, acknowledging the interplay between biological predispositions and environmental influences (Neimeyer & Neimeyer, 2002).

- Uniqueness vs. Universality- PCT celebrates the uniqueness of individuals while recognizing patterns of commonality. Each person develops distinct constructs based on their experiences, yet shared constructs enable social cohesion and mutual understanding (Walker & Winter, 2007).

- Growth and Change- Personal growth occurs through the continuous revision of constructs. By encountering new experiences and adapting their constructs, individuals can achieve greater self-awareness and resilience. This adaptability underscores the transformative potential of PCT.

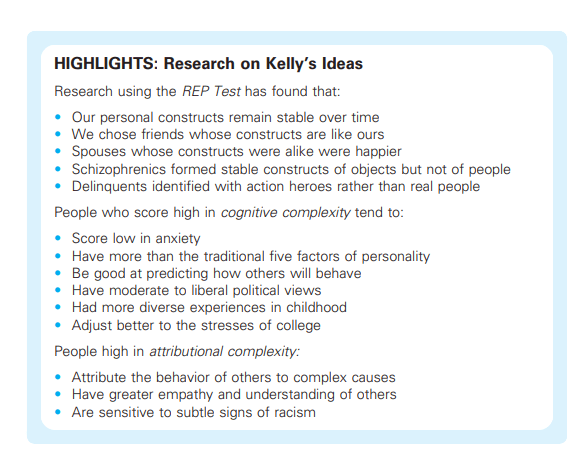

Research on Kelly’s Theory

Criticism to Personal Construct Theory

While George Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory (PCT) has made significant contributions to psychology, it has not been without its criticisms. These critiques address the theory’s conceptual, methodological, and practical aspects, highlighting potential limitations in its application and interpretation. This includes-

- Subjectivity of Constructs- One of the primary criticisms of PCT is the subjective nature of constructs. Critics argue that the theory relies heavily on individuals’ internal perceptions, which can be difficult to measure or validate empirically (Adams-Webber, 2001). Unlike theories grounded in observable behaviors or biological processes, PCT depends on self-reported data, which can introduce bias or inaccuracies.

- Lack of Universality- Although Kelly emphasized the individuality of constructs, some scholars question whether this focus undermines the search for universal principles in psychology. By prioritizing personal interpretations, PCT may overlook broader psychological patterns that transcend individual differences (Neimeyer, 1995).

- Limited Empirical Support- PCT has been critiqued for its limited empirical support compared to other psychological theories. Its focus on qualitative methodologies, such as the Repertory Grid Technique, may lack the rigor of experimental approaches favored in contemporary psychology (Winter, 2003).

- Oversimplification of Human Complexity- Some critics argue that PCT oversimplifies the complexity of human cognition by reducing it to a series of bipolar constructs. Human behavior and thought processes often involve multidimensional, non-linear factors that may not fit neatly into dichotomous categories (Walker & Winter, 2007).

- Insufficient Attention to Emotion- PCT has been criticized for its limited focus on emotional processes. While the theory emphasizes cognition and prediction, it does not thoroughly address the role of emotions in shaping constructs or influencing behavior (Leitner, 1985). Critics argue that this omission limits the theory’s ability to fully explain human experience, particularly in emotionally charged situations.

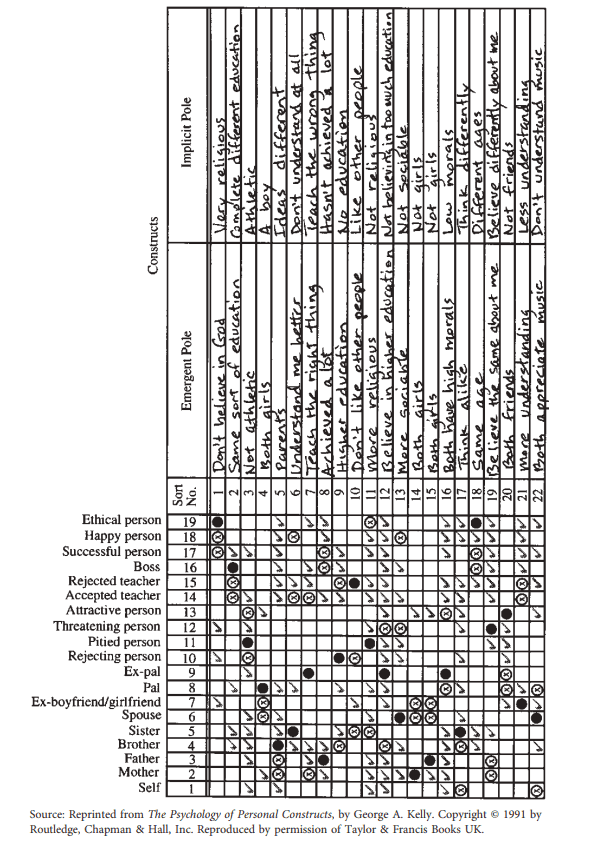

Role Construct Repertory Test

Conclusion to Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory

George Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory provides a robust framework for understanding how individuals interpret and navigate their world. By emphasizing the dynamic and subjective nature of constructs, PCT highlights the active role of individuals in shaping their reality. The eleven corollaries offer a comprehensive lens for exploring the diversity and adaptability of human thought. Ultimately, Kelly’s theory underscores the transformative potential of reinterpreting and revising our constructs to foster personal growth, resilience, and meaningful connections.

References to Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory

Adams-Webber, J. R. (2001). Personal construct theory and practice: The legacy of George Kelly. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 14(3), 255–260.

Hall, C. S., & Lindzey, G. (1970). Theories of Personality (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Kelly, G. A. (1955). The Psychology of Personal Constructs (Vol. 1 & 2). New York: Norton.

Leitner, L. M. (1985). Emotion in Kelly’s personal construct theory: A neglected dimension. Clinical Psychology Review, 5(1), 41–56.

Neimeyer, R. A. (1995). Constructivist approaches to psychological assessment. Psychological Assessment, 7(4), 395–404.

Neimeyer, R. A., & Neimeyer, G. J. (2002). Constructivist psychology: Reflections on the legacy of George Kelly. Canadian Psychology, 43(2), 109–120.

Schultz, D. P., & Schultz, S. E. (2017). Theories of Personality (11th ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning.

Walker, B. M., & Winter, D. A. (2007). The elaboration of personal construct psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 453–477.

Winter, D. A. (2003). Repertory grid technique as a research method. In F. Fransella (Ed.), International Handbook of Personal Construct Psychology (pp. 33–47). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 15,060 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, November 30). Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory and Important 11 Corollaries. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/kellys-personal-construct-theory/