Introduction

Environmental behavior, encompassing actions that contribute to ecological preservation, is shaped by an intricate blend of individual habits, social influences, and situational factors. These behaviors are critical in addressing pressing global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. However, fostering pro-environmental behavior requires more than mere awareness; it demands a deeper understanding of how habits and social practices influence actions.

Read More- What is Sustainability?

Foundations of Behavior Modification

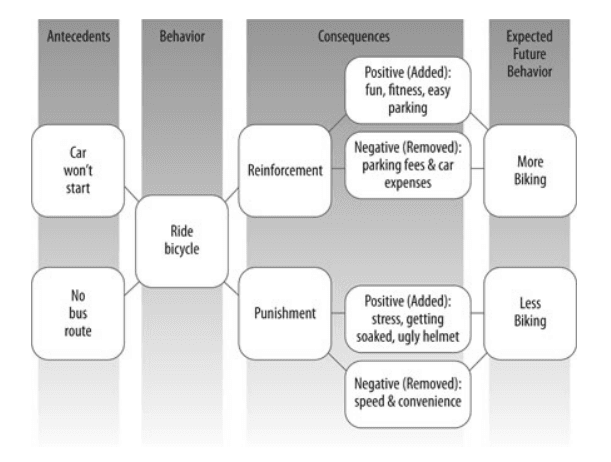

Behavior modification is rooted in the principles of operant conditioning, which emphasize the role of reinforcement and punishment in shaping behavior. As noted by Skinner (1991), behavior is influenced significantly by its consequences—whether reinforcing (increasing the likelihood of the behavior) or punishing (reducing its probability). Consequences can be either positive (adding a stimulus) or negative (removing a stimulus).

Behavioural Modification

Antecedents

Antecedents are cues or prompts that guide individuals toward specific behaviors. They can range from informational signs to subtle social cues. For instance, a student mentioned being influenced by a simple yet effective sign above the bathroom lights that read: “Save a Light, Kill a Watt!” Such reminders act as antecedents, making environmentally friendly actions more likely by bringing awareness to an opportunity for sustainable behavior.

Another example involves bike commuting. Visible bike lanes and easily accessible parking serve as antecedents that encourage people to choose cycling over driving. Without such cues, even well-intentioned individuals may default to less sustainable choices due to perceived inconvenience.

Consequences

Consequences determine whether a behavior will persist. Positive reinforcement—adding a rewarding stimulus—strengthens desirable behaviors. For example, deposit-refund systems, such as bottle bills, offer monetary rewards for recycling. In states with these laws, beverage container recycling rates are significantly higher than the national average (Container Recycling Institute, 2013). Conversely, punishment, such as social disapproval or monetary fines, decreases the likelihood of undesirable behaviors. For example, a mother reprimanding her child for throwing a recyclable can in the trash uses punishment to discourage such actions.

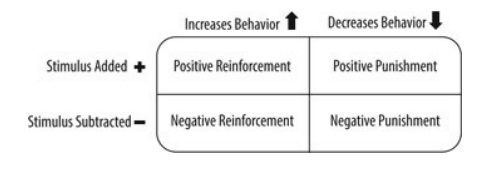

Skinner’s analysis highlights four types of behavioral consequences-

Types of Reinforcement

- Positive Reinforcement- Adding a pleasant stimulus, like receiving a refund for recycling bottles.

- Negative Reinforcement- Removing an aversive stimulus, such as avoiding parental scolding by complying with recycling norms.

- Positive Punishment- Adding an unpleasant stimulus, like a parking ticket for driving in a restricted area.

- Negative Punishment- Removing a pleasant stimulus, such as losing access to a free parking permit for excessive vehicle use.

The interpretation of consequences is subjective. For example, bus riding might feel reinforcing in urban areas with convenient routes and expensive parking but punishing in rural areas with infrequent service and distant stops.

Read More- Operent Conditioning

Reinforcement and Emotions

- While punishment can deter unsustainable behaviors, reinforcement is generally more effective for long-term behavioral change (DeYoung, 2000). For instance, rewarding individuals for cycling to work, such as offering discounts at local coffee shops, increases the appeal of the behavior without constraining other choices. Reinforcement fosters a sense of autonomy and positive association with the action, making it more likely to become habitual.

- Beyond tangible rewards, emotional states also function as reinforcers or punishers. A student who enjoys cycling to school not only benefits from exercise and fresh air but also associates the activity with feelings of joy. These emotional reinforcers enhance the likelihood of repeating the behavior. Conversely, guilt and shame from failing to recycle or conserve energy can act as emotional punishers, discouraging neglectful behavior in the future.

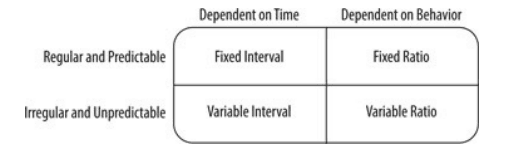

Schedules of Reinforcement

Schedules of Reinforcement

- Immediate vs. Delayed Consequences- The timing of consequences significantly influences their effectiveness. Immediate rewards or punishments are more impactful than delayed ones. For instance, receiving a small refund for returning a bottle provides instant gratification, reinforcing the habit of recycling.

- Continuous vs. Intermittent Reinforcement- Continuous reinforcement, where every instance of a behavior is rewarded, is effective for initiating change but may falter once the rewards cease. In contrast, intermittent reinforcement—rewarding behavior unpredictably—yields more durable habits. For example, a community bike-share program could offer random discounts or free services to frequent riders, maintaining their interest and commitment over time.

Social Influences

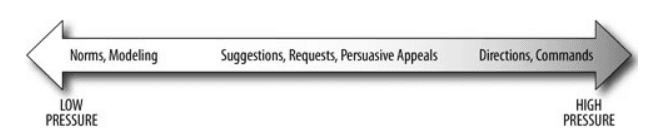

Social influence is mediated by social norms, modeling, feedback and social status. The influence the initiation and maintaince of pro-environmental behaviour.

Continuum of Social Influence

- Social Norms- These are unwritten rules about acceptable conduct, significantly shape environmental behavior. Descriptive norms describe what people typically do in a situation, while injunctive norms specify what is considered appropriate (Schultz et al., 2007). For instance, seeing neighbors compost their kitchen waste (descriptive norm) and knowing that society values composting (injunctive norm) can motivate individuals to follow suit.

- Modeling- It referes to observing and imitating others—is another powerful social influence. In a classic experiment, researchers increased water conservation in a university gym by having confederates demonstrate efficient shower practices. Compliance rates surged when one or two individuals modeled the behavior, demonstrating the contagious nature of visible actions (Aronson & O’Leary, 1983).

- Social feedback- This further reinforces behavior. Positive reinforcement, such as praise for recycling efforts, encourages repetition, while normative feedback comparing energy use with peers fosters a sense of responsibility. For example, displaying a smiley face on utility bills for households consuming less energy than their neighbors effectively reduced energy consumption (Schultz et al., 2007).

- Status- Concerns about social status also drive environmental behavior. High-status individuals may adopt eco-friendly practices as a form of “costly signaling,” demonstrating their commitment to collective well-being. Products like electric vehicles or solar panels serve as both functional tools and status symbols, showcasing environmental consciousness while satisfying status-driven motivations (Griskevicius et al., 2010).

The Tragedy of the Commons

The “tragedy of the commons” is a social dilemma where individuals prioritize short-term personal gains over the long-term collective good, often leading to resource depletion (Hardin, 1968). A classic example involves shared grazing land. Farmers who overgraze their animals on communal land may benefit individually, but the collective overuse degrades the resource, ultimately harming everyone, including the farmers themselves.

This principle is evident in modern contexts, such as overfishing in international waters or the overuse of fossil fuels. Addressing such dilemmas requires strategies that align individual incentives with collective sustainability goals. For instance, fisheries management programs that limit catch sizes and reward sustainable practices can mitigate overexploitation.

Overcoming Barriers

Behavioral engineering involves modifying environmental contingencies to facilitate sustainable behaviors. This approach employs antecedent strategies, such as providing accessible recycling bins, and consequence strategies, like rewarding eco-friendly actions.

For example- To reduce single-use plastic consumption, governments can combine antecedent and consequence strategies. Prompts like signage reminding shoppers to carry reusable bags act as antecedents, while incentives such as discounts for using reusable bags serve as reinforcing consequences. The introduction of a plastic bag charge in Wales reduced disposable bag usage significantly, demonstrating the effectiveness of combining strategies (Poortinga et al., 2013).

Informational feedback, such as personalized energy consumption reports, can sustain behavior change by providing a sense of progress. Highlighting the cumulative impact of individual actions—e.g., “Your efforts have saved 10 trees this month”—adds an intrinsic sense of accomplishment, motivating continued engagement.

Conclusion

Habits and social practices are critical drivers of environmental behavior. Through behavior modification techniques like reinforcement, modeling, and feedback, sustainable actions can become habitual. Additionally, addressing collective challenges like the tragedy of the commons requires aligning individual incentives with societal goals. By engineering supportive environments and leveraging social influences, policymakers and individuals can foster a culture of sustainability.

References

Aronson, E., & O’Leary, M. (1983). The effects of modeling and feedback on water conservation in a men’s shower room. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13(2), 174–181.

Container Recycling Institute. (2013). Bottle bills and recycling rates. Retrieved from container-recycling.org

DeYoung, R. (2000). Expanding and evaluating motives for environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 509–526.

Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., & Van den Bergh, B. (2010). Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 392–404.

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248.

Milinski, M., Sommerfeld, R. D., Krambeck, H.-J., Reed, F. A., & Marotzke, J. (2008). The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(7), 2291–2294.

Neal, D. T., Wood, W., & Quinn, J. M. (2006). Habits—A repeat performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(4), 198–202.

Poortinga, W., Whitmarsh, L., & Suffolk, C. (2013). The introduction of a single-use carrier bag charge in Wales: Attitude change and behavioral spillover effects. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 240–247.

Schultz, P. W., Nolan, J. M., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2007). The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychological Science, 18(5), 429–434.

Scott, B. A., Amel, E. L., Koger, S. M., & Manning, C. M. (2016). Psychology for sustainability (4th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Skinner, B. F. (1991). The power of the (unsustainable) situation. In Behaviorism and environmental preservation. Cambridge: Behaviorist Press.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 16,609 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, December 28). Habits and 4 Important Mediations of Social Influence on Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/habits-and-pro-environmental-behaviour/