Introduction of Guilford’s Theory of Creativity

J.P. Guilford defined creativity as the ability to produce ideas that are both novel and useful, emphasizing divergent thinking as central to the creative process.

According to Guilford, creativity is characterized by the ability to generate multiple solutions or ideas, which involves flexibility, originality, fluency, and elaboration. He described creativity as a type of thinking that goes beyond conventional problem-solving, involving the capacity to transform and reinterpret information in ways that lead to unique and innovative solutions (Guilford, 1950; Guilford, 1986).”

He first distinguished between convergent and divergent thinking in the context of creativity research, suggesting in his Structure of Intellect (SOI) Model that divergent thinking is essential for creativity (Guilford, 1950). This model redefined intelligence by highlighting how creative individuals employ a unique set of cognitive skills beyond those measured in traditional IQ assessments.

Structure of Intellect Model

The Structure of Intellect (SOI) model conceptualizes intelligence as a multifaceted and multidimensional construct. Unlike traditional intelligence models, which often focus narrowly on IQ or a single “general intelligence” factor (g), the SOI model proposes that intelligence is composed of multiple, distinct abilities. Guilford identified three dimensions within intelligence: Operations, Content, and Products, each subdividing into multiple specific abilities, ultimately proposing over 150 unique intellectual abilities.

- Operations- This dimension represents the types of mental processes used to solve problems, such as-

- Cognition- Recognizing and understanding information.

- Memory- Retaining and recalling information.

- Divergent production- Generating multiple solutions to a problem.

- Convergent production- Narrowing down to a single correct solution.

- Evaluation- Assessing information and making judgments.

- Content- This dimension involves the types of information processed, categorized into-

- Figural- Visual and sensory information.

- Symbolic- Abstract symbols like letters or numbers.

- Semantic- Language and verbal content.

- Behavioral- Social interactions and human behavior.

- Products- This dimension refers to the forms that the processed information takes, such as-

- Units- Simple items of information.

- Classes- Categories or groupings of items.

- Relations- Connections between items.

- Systems- Organized structures of items.

- Transformations- Changes or alterations in items.

- Implications- Predictions or inferences based on items.

The SOI model’s broad categorization offers a more comprehensive view of intelligence, accommodating both analytical and creative abilities, and supports the idea that intellectual abilities can be developed with practice. This multidimensional approach has influenced educational methods and talent identification by promoting tailored learning strategies that align with each individual’s specific intellectual strengths.

Structure of Intellect Model

Read More- What is Creativity

Divergent vs Convergent Thinking

Divergent vs Convergent Production

Convergent Thinking- Guilford defined this as the thought process focused on narrowing multiple solutions to find the single correct answer, often evaluated in IQ tests (Guilford, 1950). For instance, solving a mathematical equation with one definitive solution reflects convergent thinking.

Divergent Thinking- In contrast, divergent thinking is associated with creativity, emphasizing the generation of numerous solutions to a problem. Guilford proposed that divergent thinking encompasses the exploration of unconventional ideas, exemplified by brainstorming or finding diverse uses for a common object (Guilford, 1986).

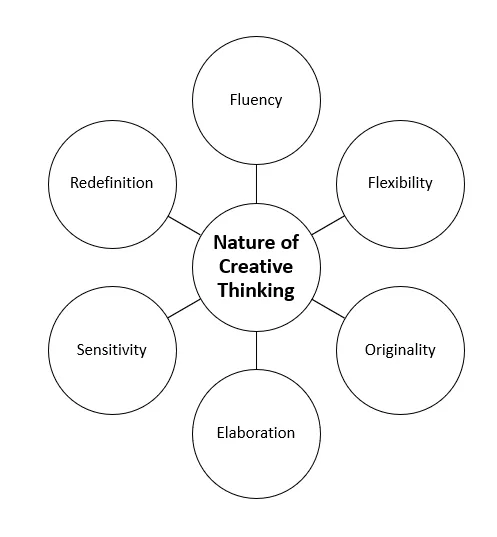

Nature of Creative Thinking

Guilford (1986) identified 6 essential components within divergent thinking that support creativity-

Nature of Creativity

- Fluency- The ability to generate numerous ideas or solutions. For example, listing multiple uses for a paperclip demonstrates fluency.

- Flexibility- The capacity to shift between different types of ideas. Flexible thinkers might suggest various categories, such as artistic, practical, or social uses for the same object.

- Originality- Producing unique and novel ideas. Individuals demonstrating originality might propose uncommon solutions that deviate from standard responses.

- Elaboration- The skill of adding detail to ideas, such as describing a paperclip’s potential as a sculpture tool.

- Sensitivity- Identifying overlooked challenges and potential opportunities.

- Redefinition- Viewing familiar items or problems in new ways, thereby promoting innovative solutions.

Guilford proposed that creativity could be assessed by measuring the variety of responses an individual can provide to a single test item (Guilford, 1967). For example, participants listing unique uses for an object reflects their capacity for divergent production and highlights their creativity.

Beyond Divergent Thinking

While Guilford emphasized divergent thinking, he clarified that creativity encompasses additional skills, such as:

- Sensitivity to Problems- Recognizing subtle or complex issues in situations where others may not perceive them (Guilford, 1986).

- Redefinition Abilities- Transforming thought patterns to reinterpret problems, promoting freedom from functional fixedness and allowing for unconventional solutions.

For example, research on creativity tasks has shown that participants generating solutions for broad societal issues demonstrate both sensitivity to problems and the capacity for redefinition, indicating a high degree of creativity (Guilford, 1986).

Intelligence and Creativity

Guilford argued for a broader approach to intelligence beyond the limitations of traditional IQ measures, suggesting that creative talents include a diversity of abilities (Guilford, 1950). His SOI model prefigured multi-dimensional intelligence theories, such as Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences.

In educational settings, Guilford’s approach supports encouraging students to explore varied problem-solving strategies that foster both convergent and divergent thinking skills. For instance, a project on environmental conservation allows students to narrow down options (convergent thinking) while exploring numerous solutions (divergent thinking), fostering flexibility, originality, and adaptability (Guilford, 1967).

Strenghts and Weaknesses of Guilford’s Theory of Creativity

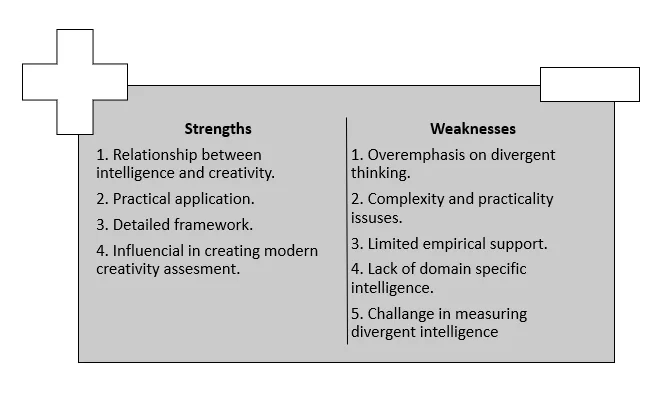

Strengths of Guilford’s Theory of Creativity

Some major strengths of the theory include-

- Broadening the Concept of Intelligence- Guilford’s approach expanded the view of intelligence to include cognitive processes not assessed by traditional IQ tests, such as divergent thinking and creativity. By identifying specific cognitive operations like flexibility, originality, and fluency, his model underscored the importance of multiple cognitive abilities, enriching our understanding of intelligence beyond conventional definitions (Guilford, 1967).

- Practical Application in Education- Guilford’s theory has influenced educational practices, particularly in promoting creativity in classrooms. His model encourages teachers to integrate activities that foster divergent thinking, helping students explore multiple solutions to a problem and develop originality and flexibility. For instance, brainstorming and open-ended problem-solving tasks in classrooms are based on principles Guilford emphasized (Guilford, 1986).

- Detailed Framework for Understanding Creativity- Guilford’s breakdown of divergent thinking into components like fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration provides a structured framework for studying creativity. This approach allows researchers and educators to analyze and measure specific aspects of creative thinking, leading to more nuanced creativity assessments (Guilford, 1986).

- Influence on Modern Creativity Assessments- Guilford’s work laid a foundation for creativity measurement tools, influencing tests like the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT), which evaluate similar aspects of divergent thinking. His contributions set the stage for empirical studies on creativity, establishing measurable criteria for assessing creative potential in individuals (Torrance, 1974).

Weaknesses of Guilford’s Theory of Creativity

Some major weaknesses of the theory includes-

- Overemphasis on Divergent Thinking- While Guilford emphasized divergent thinking as central to creativity, later research has shown that creativity often requires both divergent and convergent thinking. For example, innovative problem-solving requires narrowing down options to the most feasible solution (convergent thinking), which Guilford’s theory largely downplays (Runco, 2004).

- Complexity and Practicality Issues- The SOI model’s detailed categorization of intelligence, with over 100 different cognitive abilities, has been criticized for being too complex and difficult to apply in practical settings. This level of complexity makes the model challenging to use for both assessment and educational purposes without extensive testing and resources (Carroll, 1993).

- Limited Empirical Support for Distinct Components- Although Guilford’s model categorizes divergent thinking into specific components, such as fluency, flexibility, and originality, research does not always support these as independent constructs. Studies have found overlap among these components, suggesting they may not be as distinct as Guilford proposed (Kim, 2006).

- Insufficient Focus on Context and Domain-Specific Creativity- Guilford’s theory largely treats creativity as a generalized cognitive ability rather than acknowledging the influence of domain-specific knowledge and expertise. Later theories, such as Amabile’s Componential Model of Creativity, argue that creativity is highly context-dependent, requiring both skill in a specific domain and intrinsic motivation, areas not emphasized in Guilford’s theory (Amabile, 1996).

- Challenges in Measuring Divergent Thinking- While Guilford’s approach advanced creativity assessment, measuring divergent thinking remains challenging. Scores for creativity assessments based on divergent thinking (e.g., fluency or originality) can vary depending on subjective judgments, leading to concerns about reliability and validity (Kaufman & Baer, 2004).

Conclusion

J.P. Guilford’s theory of creativity was groundbreaking, particularly in its distinction between divergent and convergent thinking and its structured approach to understanding cognitive abilities. His Structure of Intellect (SOI) Model broadened the traditional view of intelligence by emphasizing creative capacities like fluency, flexibility, and originality.

Guilford’s insights reshaped creativity research, influencing assessments, educational practices, and later theories of intelligence by highlighting that creativity is a complex and multi-dimensional process.

However, while Guilford’s focus on divergent thinking was essential in advancing creativity studies, the theory has its limitations. Its complexity and overemphasis on divergent thinking alone do not fully account for the role of convergent thinking, context, and domain-specific expertise in creative endeavors.

Despite these critiques, Guilford’s theory remains a foundational work, emphasizing the need for a broader, more inclusive understanding of cognitive abilities, thus paving the way for further advancements in creativity and intelligence research. His legacy persists as researchers continue to explore the multi-faceted nature of human creativity and intelligence.

References

Matlin, M. W. (2009). Cognition (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Sternberg, R. J., & Sternberg, K. (2012). Cognitive Psychology (6th ed.). Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in Context: Update to the Social Psychology of Creativity. Westview Press.

Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-Analytic Studies. Cambridge University Press.

Kaufman, J. C., & Baer, J. (2004). Creativity across Domains: Faces of the Muse. Psychology Press.

Kim, K. H. (2006). “Can We Trust Creativity Tests? A Review of the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT).” Creativity Research Journal, 18(1), 3-14.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, November 3). Guilford’s Theory of Creativity- 6 Key Components of Creative Thinking. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/guilfords-theory-of-creativity/