Introduction to FIRO-B

The FIRO-B (Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation – Behavior) test is a psychometric tool designed to assess interpersonal behavior and needs. Developed by Will Schutz in 1958, this test remains highly relevant in personal development, team building, and leadership coaching.

FIRO-B provides a framework for understanding how individuals interact with others across three primary dimensions of interpersonal behavior- Inclusion, Control, and Affection. These behaviors are further categorized into Expressed (how individuals act towards others) and Wanted (how they wish others would act towards them) orientations.

Background and Development of FIRO-B

FIRO-B was created during Will Schutz’s work on group dynamics for the U.S. Navy. Schutz aimed to understand how individuals’ interpersonal behaviors affected group cohesion and performance (Schutz, 1958). Schutz’s foundational premise was simple yet profound: “people need people.”

He hypothesized that people’s actions in social and professional contexts are driven by three fundamental needs:

- Inclusion- The need to belong and connect with others.

- Control- The need for influence and order.

- Affection- The need for emotional closeness and trust.

The expressed and wanted orientations of these needs form the foundation of the FIRO-B model. Schutz believed that understanding and balancing these interpersonal needs could improve relationships and enhance group effectiveness.

Schutz’s theoretical framework was shaped not only by his own observations of team dynamics but also by significant influences from classic psychological thinkers. Drawing on insights from Freud, Adorno, Fromm, Adler, and Jung, Schutz integrated concepts from psychoanalysis and humanistic psychology to form a more comprehensive understanding of interpersonal needs. These influences helped him identify three fundamental needs—Inclusion, Control, and Affection—which he believed were central to human interaction and could explain a range of behaviors in group and individual settings.

Over time, FIRO-B evolved into a psychometric instrument used widely beyond military contexts, gaining applications in areas such as leadership development, team building, and personal growth. Through this evolution, FIRO-B has become a valuable tool for examining how interpersonal needs influence behavior and shaping modern approaches to understanding human relations in both personal and professional spheres.

Read More- Industrial Psychology

FIRO-B

FIRO Awareness Scales

The FIRO Awareness Scales are a series of instruments designed to assess these needs from various perspectives (behavior, feelings, values, etc.). They include-

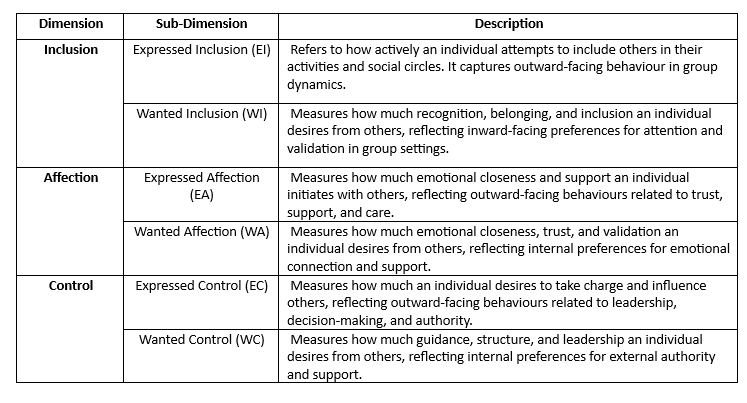

3 Domains of FIRO-B

The domains in FIRO-B include the following concepts-

Domains in FIRO-B

1. Inclusion

The Inclusion dimension of the FIRO-B model talks about the interpersonal need for belonging, connection, and participation. It evaluates how much individuals seek to involve others in their social interactions and how much they, in turn, desire to be included. This dimension is pivotal for understanding how people navigate group settings such as work teams, friendships, or family relationships (Schutz, 1958). People differ widely in how they express or seek inclusion, with this variance shaping their social dynamics and role preferences.

1A. Expressed Inclusion (EI)–

Expressed Inclusion refers to how actively an individual attempts to include others in their activities and social circles. It captures the outward-facing behavior of someone in group dynamics, demonstrating their openness to fostering connections and creating an inclusive environment (Schutz, 1992). Individuals with high EI are naturally sociable and derive energy from group interactions. Whereas individuals with low EI prefer solitary activities and are less inclined to involve others in their plans.

1B. Wanted Inclusion (WI)-

Wanted Inclusion measures how much recognition, belonging, and inclusion an individual desires from others. It reflects the inward-facing preference of an individual for receiving attention, validation, or acknowledgment in group settings (Hammer & Schnell, 2000). Those with high WI experience fulfillment when they are frequently included, recognized, or given opportunities to participate. Individuals with low WI value their independence and are less concerned about being included in group activities.

2. Affection

The Affection dimension evaluates the need for emotional warmth, trust, and closeness in relationships. It explores how individuals form personal bonds and how much emotional validation they seek from others. This dimension is central to building trust and fostering loyalty in both professional and personal contexts (Schutz, 1958).

2A. Expressed Affection (EA)-

Expressed Affection measures how much emotional closeness and support an individual initiates with others. It reflects outward-facing behaviors related to building trust, offering support, and expressing care (Hammer & Schnell, 2000). Individuals with high EA are warm, approachable, and prioritize meaningful relationships. They often express their care and concern openly. Individuals with low EA are reserved and may struggle to express emotions or build close connections. They focus more on tasks than relationships.

2B. Wanted Affection (WA)-

Wanted Affection measures how much emotional closeness, trust, and validation an individual desires from others. It reflects internal preferences for emotional connection and support (Schutz, 1992). Individuals with high WA value emotional bonds and seek reassurance, warmth, and empathy in relationships. Individuals with low WA are self-reliant and may find emotional attention unnecessary. They prioritize independence over emotional validation.

3. Control

The Control dimension evaluates how individuals handle authority, power, and responsibility in their relationships. It identifies preferences for directing others or being directed, revealing how people approach decision-making and structure. This dimension is vital in leadership, delegation, and organizational dynamics (Furnham, 2008).

3A. Expressed Control (EC)-

Expressed Control measures how much an individual desires to take charge and influence others. It reflects outward-facing behaviors related to leadership, decision-making, and establishing authority (Hammer & Schnell, 2000). Individuals with high EC are natural leaders who feel comfortable taking charge and influencing group outcomes. They thrive in structured environments where they can exercise authority. Individuals with low EC are less inclined to take charge or assume responsibility. They prefer to contribute without asserting authority.

3B. Wanted Control (WC)-

Wanted Control measures how much guidance, structure, and leadership an individual desires from others. It reflects an internal preference for external authority and support (Schutz, 1992). Individuals with high WC thrive under supportive leadership and structured environments. They seek clarity, consistency, and guidance in their roles. Individuals with low WC value autonomy and independence. They prefer minimal external control or guidance and resist micromanagement.

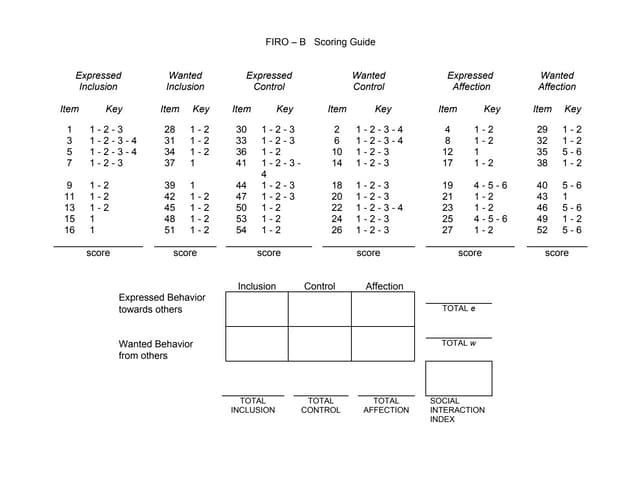

Firo b – scoring-guide

Psychometric Properties of the FIRO-B Test

The FIRO-B test is a psychometric tool designed to assess interpersonal needs in the domains of Inclusion, Control, and Affection.

Reliability of FIRO-B

It refers to the consistency of a test in measuring what it intends to measure over time and across contexts. FIRO-B demonstrates good internal consistency for its six scales (Expressed and Wanted needs for Inclusion, Control, and Affection). Studies report Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.85 to 0.93, indicating high reliability (Hammer & Schnell, 2000). The test exhibits satisfactory stability over time, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.80 across intervals of several weeks.

Validity of FIRO-B

it assesses whether the FIRO-B accurately measures interpersonal needs. The structure of the test aligns well with the theoretical model proposed by William Schutz, who defined interpersonal behaviors along the axes of Inclusion, Control, and Affection (Schutz, 1958).

Factor analysis has supported the three-domain structure, affirming its construct validity. FIRO-B correlates moderately with similar constructs in other interpersonal tools, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and the Social Styles model, reflecting alignment with broader interpersonal psychology.

FIRO-B scores have shown moderate correlations with Fiedler’s Least Preferred Co-worker (LPC) scale (ranging from -.43 to .46), indicating that the interpersonal needs measured by FIRO-B align with key leadership attributes identified in LPC, such as task-oriented versus relationship-oriented leadership styles (Hammer & Schnell, 2000).

FIRO-B’s criterion validity extends to values related to community service, with correlation coefficients between .05 and .27. This suggests that individuals’ interpersonal needs, as assessed by FIRO-B, may relate to their inclinations toward community involvement and service (Hammer & Schnell, 2000).

Norms of FIRO-B

The test has been normed across diverse populations, with a large sample size to ensure statistical reliability. Norm groups encompass various professions, cultural backgrounds, and age ranges, ensuring broad applicability (Hammer & Schnell, 2000).

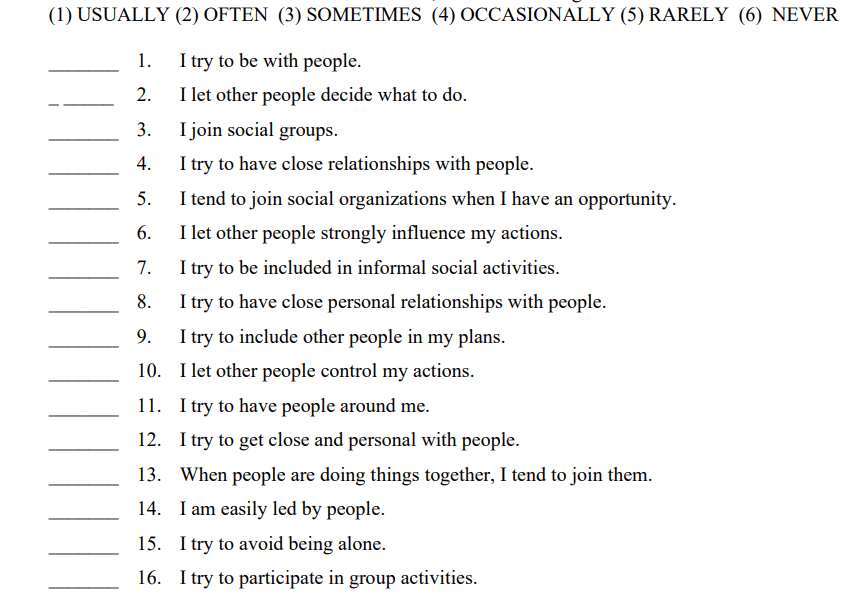

Sample Questions of FIRO-B

FIRO-B Sample Questions

Applications of FIRO-B

FIRO-B is widely used across contexts to enhance understanding of interpersonal dynamics, identify compatibility, and optimize team performance.

- Organizational Development- FIRO-B helps identify interpersonal strengths and potential conflicts among team members. For example, pairing individuals with complementary Expressed and Wanted needs can foster collaboration. By evaluating leaders’ Expressed and Wanted Control scores, organizations can assess leadership styles, identify areas for growth, and tailor coaching strategies. The tool facilitates discussions about interpersonal mismatches, such as a high Expressed Control manager working with a high Wanted Affection subordinate.

- Personal Development- The test encourages individuals to understand their interpersonal preferences and adapt their behavior to enhance relationships. Counselors use FIRO-B to uncover unmet interpersonal needs in couples, helping them build stronger emotional connections.

- Educational Settings- FIRO-B can guide mentorship programs by matching mentors and mentees based on complementary interpersonal preferences. The test helps students identify professions that align with their interpersonal tendencies, such as high Inclusion roles (e.g., teaching) or low Affection roles (e.g., research).

- Clinical Use- Psychotherapists use FIRO-B to assess clients’ interpersonal struggles, particularly in areas such as social anxiety, authority issues, or emotional detachment. It can identify personality traits that may underlie behavioral disorders, though it is typically used as a supplemental tool rather than a standalone diagnostic measure.

Limitations of the FIRO-B Test

Despite its strengths, the FIRO-B test has limitations that must be considered in interpretation and application.

- Oversimplification- FIRO-B reduces complex interpersonal dynamics into three domains, which may oversimplify multifaceted relationships. Critics argue that it does not account for deeper personality factors like trauma or cultural differences (Furnham, 2008).

- Static Interpretation- The test assumes stable interpersonal needs over time, potentially overlooking situational or developmental changes. For instance, an individual’s Inclusion needs may fluctuate during significant life transitions such as career changes or parenthood.

- Cultural Bias- FIRO-B was originally developed in a Western context, raising concerns about cultural bias. For example, high Expressed Control may be valued in individualistic cultures but seen as intrusive in collectivist societies.

- Self-Report Bias- The test relies on self-reporting, making it vulnerable to social desirability bias or inaccurate self-perceptions. Individuals may underreport or exaggerate certain needs depending on their context.

- Limited Scope- While useful for interpersonal insights, FIRO-B does not address other psychological constructs such as cognitive ability, emotional intelligence, or motivational drives, limiting its standalone utility in complex assessments.

Conclusion

The FIRO-B test offers profound insights into how individuals engage with others and how they wish to be engaged in return. By examining the nuances of Inclusion, Control, and Affection—each with its expressed and wanted orientations—it enables individuals and organizations to foster healthier, more productive relationships.

References

Schutz, W. C. (1958). FIRO: A three-dimensional theory of interpersonal behavior. Psychological Review, 65(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045257

Hammer, M. R., & Schnell, L. (2000). FIRO-B manual. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Furnham, A. (2008). Psychometric testing: A practical guide for users. Psychology Press.

Schutz, W. C. (1992). The interpersonal underworld: A psychodynamic view of the FIRO model. Journal of Personality Assessment, 58(2), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5802_7

Hammer, M. R., & Schnell, L. (2000). FIRO-B manual. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Defining Interpersonal Relations

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), interpersonal relations are the patterns seen in an individual’s interactions with others. This concept underscores the observable and sometimes repetitive nature of social behaviors.

Similarly, Griffin (1990) describes interpersonal relationships as the reciprocal social and emotional exchanges between individuals and those in their environment, emphasizing their impact on emotional well-being.

Interpersonal Orientation (IO)

Smith & Ruiz (2007) defines Interpersonal orientation (IO) as the individual differences in a person’s preference for social interaction. Interpersonal orientation varies widely, influencing one’s behavior in group settings, friendships, and intimate relationships. This concept is important to understanding how some individuals may seek or avoid certain social exchanges. To Explain Interpersonal Orientation, Schutz gave three types of interpersonal needs (inclusion, control & affection) and two ways (Expressed & Wanted) in which needs can be portrayed (Schutz, 1958/66).

Purpose of FIRO-B

The FIRO-B is self-report test that provides a structured framework for analyzing the interpersonal needs and behaviors, offering a scientific perspective on interpersonal dynamics. It enables individuals to gain self-awareness and insight into how their own needs and behaviors align or conflict with those of others.

Evolution of FIRO-B

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, December 10). FIRO-B: Development, 3 Domains, Reliability, Validity, Norms & Practical Uses. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/firo-b/