Introduction to Eysenck’s Theory of Personality

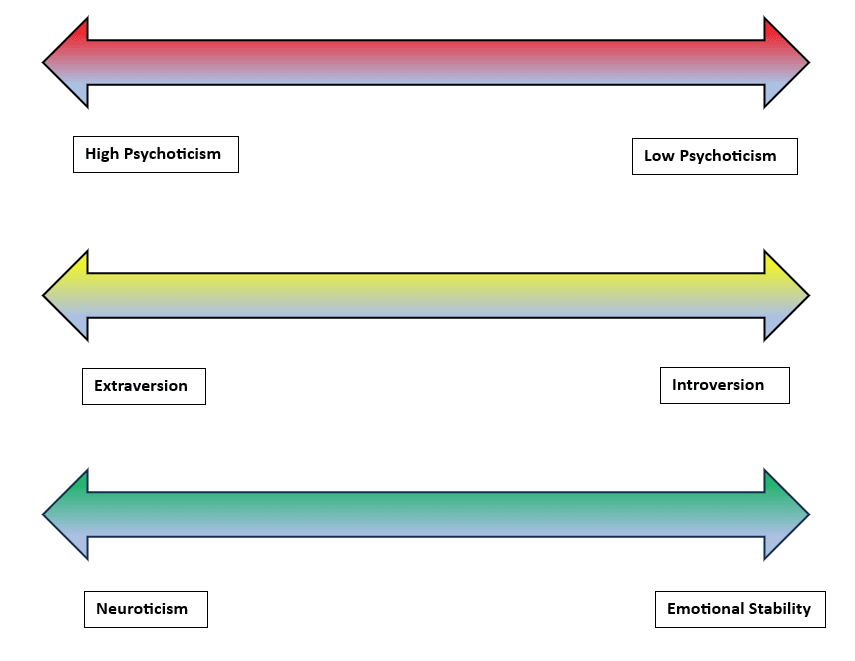

Hans Eysenck’s theory of personality (1967) is a prominent framework in psychology, recognized for its empirical rigor and its emphasis on biological underpinnings of behavior. Eysenck proposed a dimensional approach to personality, emphasizing traits as continuous variables rather than discrete categories. The theory revolves around three primary dimensions- Extraversion-Introversion (E), Neuroticism-Stability (N), and later, Psychoticism (P) (Eysenck, 1967). These dimensions form the basis of his personality model, known as the PEN model.

Read More- Personality

PEN Model

Eysenck’s PEN Model is hierarchical, comprising specific behaviors at the base and broader traits at the top (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985). Eysenck posited that these traits are biologically grounded and influenced by genetic factors.

The three primary dimensions-

- Extraversion (E)- Reflects sociability, energy, and assertiveness. Introverts, in contrast, are more reserved and introspective.

- Neuroticism (N)- Denotes emotional instability and tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety and depression.

- Psychoticism (P)- Associated with aggressiveness, creativity, and nonconformity; added later to account for antisocial tendencies.

Eysenck’s Theory of Personality- PEN Model

Extraversion-Introversion Dimension

Eysenck’s Extraversion-Introversion dimension is central to his personality theory, emphasizing how individuals respond to stimulation and social environments. It captures behavioral tendencies and preferences that stem from differences in physiological arousal.

Extraverts tend to be outgoing, sociable, and energized by external stimuli such as interactions, events, and novelty. They thrive in environments requiring quick decision-making, multitasking, and adaptability. Introverts tend to be reflective, introspective, and often shy. They are sensitive to external stimuli, making them more likely to feel overwhelmed in noisy or chaotic environments.

These differences are thought to arise from variations in cortical arousal, specifically in the reticular activating system (RAS). According to Eysenck, introverts have higher baseline cortical arousal levels, leading them to avoid overstimulating environments. Extraverts, with lower baseline levels, seek stimulation to achieve an optimal arousal state (Eysenck, 1967).

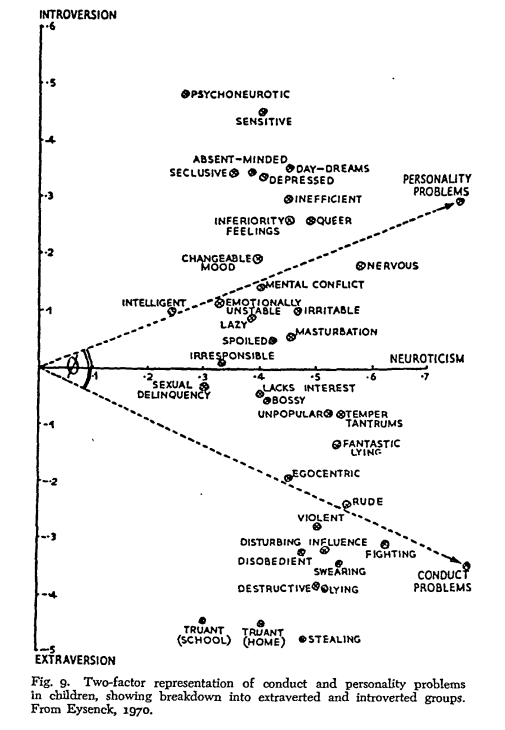

Extraversion-Intraversion and Maladaptive Behaviours

Eysenck’s famous study involved measuring the salivary response to lemon juice in extraverts and introverts (Eysenck, 1973). The study found that-

- Introverts salivated more in response to the lemon juice, indicating greater physiological reactivity to stimuli.

- This supports the theory that introverts’ heightened sensitivity results from increased baseline arousal.

Key characteristics of individuals with various scores on this dimension include-

- High Extraversion-

- Outgoing- Enjoy meeting new people and forming connections. Comfortable initiating conversations and often dominate social gatherings. Tend to have a wide circle of friends and acquaintances.

- Talkative- Naturally expressive and enjoy sharing thoughts, stories, and opinions. Engage easily in discussions, often steering conversations to keep them lively. Tend to be good at networking and public speaking.

- Enthusiastic- Exhibit high levels of energy and excitement in their interactions. Often perceived as charismatic, optimistic, and upbeat. Their enthusiasm can motivate and uplift those around them.

- Thrives in Social Settings- Feel invigorated by group activities, parties, and team-based tasks. Seek out opportunities to collaborate and bond with others. Can become restless or bored in solitary or monotonous environments.

- Enjoy Risk-Taking and Adventure- Inclined toward novelty, exploration, and trying new experiences. Enjoy activities like travel, extreme sports, or competitive environments. May take calculated risks in pursuit of excitement or reward.

2. Low on Extraversion (Introversion)-

- Reserved- Tend to observe before engaging in social interactions. Prefer small gatherings over large, boisterous groups. Often keep thoughts and feelings to themselves unless prompted.

- Introspective- Inclined toward deep self-reflection and thoughtful analysis. Spend time understanding their own motivations and emotions. May excel in creative, intellectual, or philosophical pursuits.

- Preference for Solitude- Enjoy spending time alone or engaging in solo activities like reading, writing, or crafting. Use solitude to recharge after social interactions, which they find draining. Comfortable with quiet and minimal external stimulation.

- Thoughtful and Deliberate- Careful decision-makers who prefer to weigh options and consequences before acting. Tend to think deeply before speaking, valuing precision and relevance. Focused on depth over breadth in both tasks and relationships.

- Sensitive to Overstimulation- Find loud, crowded, or chaotic environments overwhelming. May avoid prolonged exposure to high-energy social events or intense multitasking. Often need downtime to process sensory or emotional input.

Read More- Neuroticism

Neuroticism-Stability Dimension

The Neuroticism-Stability dimension focuses on emotional reactivity and regulation. It measures an individual’s propensity for experiencing negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, or depression.

Individuals with high neuroticism often experience intense emotional fluctuations. They are prone to anxiety, mood swings, and difficulty managing stress. Whereas emotionally stable individuals demonstrate resilience, calmness, and consistent emotional regulation. They cope effectively with stress and are less likely to experience prolonged negative emotional states.

Eysenck linked neuroticism to autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity, particularly heightened limbic system sensitivity to stressors. Those high in neuroticism tend to have overactive ANS responses, causing them to overreact to minor challenges (Gray, 1981).

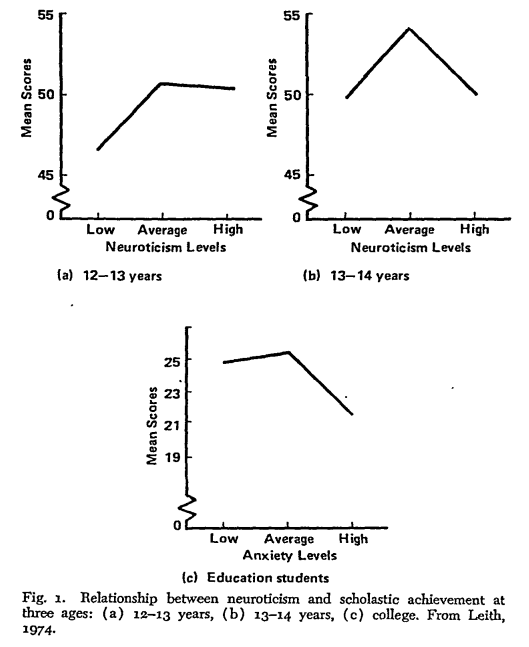

Neuroticism and Academic Achievement

Key characteristics of individuals with various scores on this dimension include-

- High on Neuroticism

- Prone to Worry- People with high neuroticism frequently engage in excessive rumination or overthinking, which leads to chronic worry. They tend to perceive situations as more threatening or challenging than they actually are. This heightened vigilance to potential stressors can cause them to be overly cautious or indecisive.

- Mood Swings- Emotional responses can be erratic and intense, leading to abrupt shifts in mood. They may feel extreme highs and lows within a short period, often influenced by minor external events. These mood swings can interfere with relationships, as others may find their reactions unpredictable.

- Emotional Instability- A tendency to be overwhelmed by stress or emotionally reactive in difficult situations. Small challenges or criticisms may trigger significant distress or feelings of inadequacy. This instability can create a cycle of negative thinking and reduced self-confidence.

- Self-Consciousness- High neuroticism is linked to increased sensitivity to social evaluation. Individuals may feel judged or scrutinized, even in benign interactions, leading to social anxiety or withdrawal. They often focus on perceived flaws, amplifying insecurities and reducing self-esteem.

- Struggles with Stress Management- Difficulty coping with stress is a hallmark of high neuroticism. These individuals may resort to maladaptive coping mechanisms like avoidance, overeating, or substance use. They may feel paralyzed in the face of challenges, unable to find solutions due to their heightened emotional responses.

- Mental Health Vulnerability- High neuroticism is a significant predictor of anxiety and depressive disorders. These individuals are more likely to experience chronic stress, generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive episodes, or other mood-related disorders. They often perceive the world as threatening, which reinforces feelings of helplessness and despair.

2. Low on Neuroticism-

- Emotional Stability- These individuals maintain a consistent emotional state, even in the face of adversity. They are less likely to be swayed by fleeting feelings of anger, sadness, or fear. Their emotional balance fosters a sense of inner peace and self-assuredness.

- Calmness- Low neuroticism is associated with a calm and composed demeanor, even in high-pressure situations. They tend to think logically and approach problems with a level head, avoiding emotional overreactions. This quality makes them dependable in crises and effective leaders.

- Resilience- Resilience is a hallmark trait of those low in neuroticism. They are quick to recover from setbacks, whether emotional, social, or professional. They view failures or challenges as opportunities for growth rather than as insurmountable obstacles. Their positive outlook contributes to better mental and physical health over time.

- Stress Management- These individuals are adept at managing stress through constructive coping strategies like problem-solving, seeking support, or engaging in relaxation techniques. Their ability to remain composed allows them to tackle problems efficiently and avoid unnecessary worry. They tend to experience less stress-related fatigue or burnout.

- Optimism and Confidence- Low neuroticism often correlates with higher self-esteem and a sense of control over one’s life. These individuals are less likely to feel victimized by circumstances and more likely to view challenges as manageable. Their optimism and confidence can make them more socially appealing and successful in interpersonal relationships.

- Mental and Physical Health Benefits- Emotional stability contributes to lower risks of mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression. Stress is less likely to take a toll on their physical health, reducing the likelihood of stress-related illnesses like cardiovascular disease.

Psychoticism Dimension

The Psychoticism dimension was added later to address personality traits linked to creativity, impulsivity, and antisocial behavior. Unlike extraversion and neuroticism, psychoticism is less universally accepted due to its broader and less clearly defined traits.

High psychoticism tend to show traits include aggression, hostility, impulsivity, and risk-taking behavior. It is associated with nonconformity and a disregard for social norms, often seen in individuals displaying antisocial tendencies. Creativity is also linked to high psychoticism, as it involves divergent thinking and a willingness to challenge conventional ideas. Whereas low psychoticism individuals are cooperative, empathetic, and conscientious, aligning more with traditional societal norms.

Eysenck speculated that psychoticism might have biological roots involving hormonal and neurochemical systems, such as elevated testosterone levels and dysregulated dopamine pathways (Eysenck & Gudjonsson, 1989).

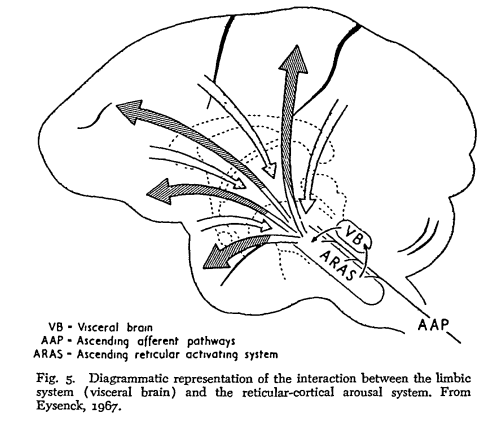

Diagram of Limbic System and RAS

Key characteristics of individuals with various scores on this dimension include-

- High Psychoticism-

- Impulsiveness- Act without considering consequences, often driven by immediate desires or emotions. Engage in spontaneous decisions, sometimes resulting in risky or reckless behavior. Impulsivity can foster innovation but may also lead to difficulties in planning or self-regulation.

- Egocentrism- Prioritize their own needs and desires over those of others. May come across as selfish or indifferent to others’ feelings. Often confident in their own abilities and ideas, which can fuel leadership in creative or entrepreneurial roles.

- Hostility- Tend to exhibit anger, aggression, or irritability, especially under stress. May struggle to maintain harmonious relationships due to their confrontational or combative nature. Can be driven by a desire to challenge authority or push boundaries.

- Risk-Taking and Antisocial Behavior- Comfortable taking physical, financial, or social risks, which can lead to success in high-stakes situations. In extreme cases, may engage in antisocial or criminal activities, disregarding rules or societal norms. High psychoticism has been linked to conditions like antisocial personality disorder in clinical contexts.

- Creativity and Nonconventional Thinking- High psychoticism can enhance creativity and innovation, as individuals are less constrained by conventional thinking. Often excel in fields that value originality, such as art, science, or entrepreneurship. Their ability to think “outside the box” can lead to breakthroughs but also to conflicts with traditional systems or expectations.

2. Low on Psychoticism-

- Altruism- Highly considerate and willing to help others, often placing others’ needs ahead of their own. Motivated by a sense of social responsibility and concern for the well-being of their community. Tend to volunteer or contribute to group efforts without seeking personal gain.

- Empathy- Strong ability to understand and share the feelings of others. Excellent at forming and maintaining close, supportive relationships. Often act as mediators in conflicts, fostering peace and understanding.

- Conformity- Prefer to adhere to societal norms and expectations, valuing rules and order. Avoid behaviors that might disrupt group harmony or cause social disapproval. May prioritize stability and tradition over innovation or risk-taking.

- Preference for Structure- Enjoy organized and predictable environments where roles and expectations are clear. Excel in settings that require cooperation, collaboration, and adherence to guidelines. Often focus on achieving goals through methodical, systematic approaches.

- Harmonious Relationships- Strive to maintain positive interactions with others, avoiding unnecessary conflict. Known for being approachable, reliable, and supportive in personal and professional contexts. Tend to prioritize group well-being over personal ambition.

Biological Basis of Personality

Eysenck believed that there exists a link between personality traits and biological processes, proposing that individual differences in temperament arise from inherited variations in brain structure and function. Some evidence of this includes-

- Genetic Evidence- Research suggests that genetic factors account for 40–60% of the variance in personality traits, particularly E, N, and P dimensions (Plomin et al., 1994). For example- extraversion and neuroticism show strong genetic underpinnings, with monozygotic (identical) twins consistently displaying higher concordance rates than dizygotic (fraternal) twins, even when raised apart.

- Neurological Correlates- Eysenck proposed that individual differences in personality are rooted in variations in brain functioning, particularly in systems that regulate arousal, emotion, and behavior. This can be seen in each aspect of the PEN model-

- Extraversion is linked to cortical arousal levels regulated by the reticular activating system (RAS). Introverts, with higher baseline cortical arousal, prefer low-stimulation environments, whereas extraverts, with lower arousal levels, seek stimulation to achieve optimal alertness (Eysenck, 1967).

- Neuroticism is associated with an overactive limbic system, which governs emotional responses. Heightened autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity in individuals with high neuroticism leads to increased stress sensitivity and difficulty regulating negative emotions (Gray, 1981).

- Psychoticism, though less clearly defined, is hypothesized to involve hormonal imbalances (e.g., elevated testosterone) and dysregulated dopamine pathways, contributing to impulsivity, creativity, and aggression.

Limitations of Eysenck’s Theory of Personality

Despite its strengths, Eysenck’s theory has faced several criticisms including-

- Reductionism- The theory reduces personality to three dimensions oversimplifies its complexity. Critics argue that traits like Agreeableness and Openness (captured in the Five-Factor Model) are overlooked (McCrae & Costa, 1997).

- Cultural and Gender Bias- Eysenck’s early studies were conducted primarily in Western populations, raising questions about their applicability to non-Western cultures. Subsequent research has addressed this to some extent.

- Psychoticism Dimension- Psychoticism has been critiqued for its lack of conceptual clarity. Traits grouped under this dimension, such as creativity and hostility, may not share common underlying mechanisms.

- Biological Determinism- Critics argue that Eysenck overemphasizes genetics and biology, neglecting the influence of environmental factors and learning on personality development.

Strengths of Eysenck’s Theory of Personality

The key strengths of the theory include-

- Scientific Rigor- Eysenck’s reliance on statistical analysis and hypothesis testing set a benchmark for psychological research.

- Predictive Utility- The theory explains a wide range of behaviors, from social interactions to susceptibility to mental health disorders.

- Cross-Cultural Validity- Research has demonstrated the universality of E and N across diverse cultures (Barrett et al., 1998).

- Interdisciplinary Impact- The model has influenced fields such as education, healthcare, and organizational management.

Conclusion

Eysenck’s theory of personality remains a cornerstone of psychological research, offering a scientifically rigorous, biologically informed framework for understanding individual differences. While it has faced criticism, its empirical foundation and practical applications ensure its enduring relevance. By integrating insights from biology, psychology, and sociology, future refinements of the PEN model could provide an even more comprehensive understanding of human behavior.

References

Barrett, P. T., Petrides, K. V., Eysenck, S. B. G., & Eysenck, H. J. (1998). The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire: An examination of the factorial similarity of P, E, N, and L across 34 countries. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(5), 805–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00026-9

Eysenck, H. J. (1967). The biological basis of personality. Charles C. Thomas.

Eysenck, H. J. (1973). Eysenck’s learning theory: A systematic and empirical analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 79(5), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033956

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, M. W. (1985). Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. Plenum Press.

Eysenck, H. J., & Gudjonsson, G. H. (1989). The causes and cures of criminality. Springer-Verlag.

Gray, J. A. (1981). A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.), A model for personality (pp. 246–276). Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-67783-0_13

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Conceptions and correlates of openness to experience. In R. Hogan, J. A. Johnson, & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 825–847). Academic Press.

Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., McClearn, G. E., & McGuffin, P. (1994). Behavioral genetics (3rd ed.). W. H. Freeman.

Stenberg, G. (1992). Personality and the EEG: Arousal and emotional arousability. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(10), 1097–1113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90034-E

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 13,984 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, November 8). Eysenck’s Theory of Personality and Its 3 Important Dimensions. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/eysencks-theory-of-personality/