Introduction

Environmental issues have gained substantial attention in recent decades due to growing concerns about sustainability, climate change, and ecological degradation. At the heart of addressing these challenges is understanding how people perceive the environment and act in ways that support or hinder environmental protection. Central to this understanding are environmental attitudes, which refer to an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of environmental issues, objects, or policies.

Read More- What is Sustainability?

The Formation of Environmental Attitudes

Attitudes are fundamental psychological constructs that shape how individuals perceive and respond to different aspects of life. According to Eagly and Chaiken (1998), an attitude is a psychological tendency expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor. In the context of environmental psychology, these entities can range from nature, environmental protection efforts, to specific policies that aim to address ecological concerns.

- Environmental attitudes are often shaped by a complex mix of cognitive, emotional, and social factors. People develop attitudes toward environmental issues through exposure to information, personal experiences, and socialization.

- While some attitudes form unconsciously—based on early experiences and environmental influences—others develop through deliberate cognitive processes (Gifford & Sussman, 2012). Environmental attitudes are influenced by geographical, economic, and cultural factors. For instance, individuals in wealthier countries, where basic needs are more than met, can afford to consider global environmental issues like climate change or biodiversity loss, whereas individuals in economically poorer countries might focus more on immediate local or regional environmental concerns (Gifford & Sussman, 2012).

- In addition to these external influences, personal relevance plays a key role in attitude formation. Issues that individuals deem personally relevant or that directly affect their lives are more likely to prompt active consideration and the formation of clear attitudes (Schultz & Zelezny, 2003).

Despite these variations, environmental attitudes have been consistently identified as a valid construct across cultures (Xiao, Dunlap, & Hong, 2013). This cross-cultural consistency suggests that environmental attitudes are not solely influenced by economic or cultural factors but may be shaped by universal psychological processes.

The Attitude-Behavior Gap

Although attitudes play a significant role in shaping behavior, they do not always translate into action. Research has consistently found that individuals who hold proenvironmental attitudes do not always engage in environmentally sustainable behaviors. Meta-analyses examining the relationship between environmental attitudes and behaviors have found modest correlations, typically around 0.40 (Hines, Hungerford, & Tomera, 1986; Bamberg & Möser, 2007). This phenomenon is referred to as the “attitude-behavior gap,” where attitudes, despite being predictive, do not always result in behavioral changes.

Several factors contribute to this gap. One major influence is the role of external factors such as social norms, perceived self-efficacy, and structural constraints.

- For instance, even if someone holds positive attitudes toward environmental protection, their behavior may be constrained by external barriers like lack of access to recycling facilities or the higher cost of environmentally friendly products.

- Social norms also play a significant role in shaping behavior; for example, in communities where environmentally harmful behaviors, such as excessive water consumption, are normalized, individuals may be less likely to act on their proenvironmental beliefs (Steg & De Groot, 2012).

Another challenge in understanding the attitude-behavior gap lies in the difficulty of accurately assessing behavior. Researchers are typically limited to self-report measures, where individuals are asked to reflect on their behaviors. However, self-reports are subject to biases, particularly social desirability bias, where participants may overreport behaviors they believe are socially acceptable or expected. This bias can distort the relationship between environmental attitudes and behaviors. Additionally, self-report measures tend to capture only explicit attitudes—those that individuals are consciously aware of and able to articulate (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). This limitation highlights the need for more nuanced tools to assess attitudes, such as those that capture implicit, nonconscious attitudes.

The Role of Values in Environmental Behavior

While attitudes are essential in shaping behavior, they are influenced by deeper, more stable personal values. Values are broad guiding principles that shape individuals’ beliefs, priorities, and decisions. Values are not limited to environmental concerns but extend to various domains of life, including personal relationships, social issues, and cultural norms. Environmental values, in particular, have been shown to directly influence environmental attitudes and behaviors.

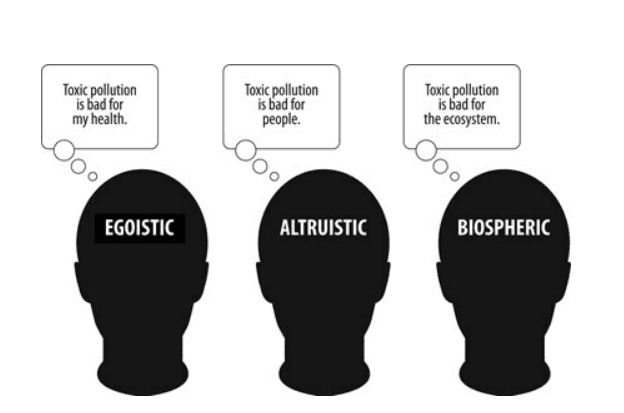

The primary types of values related to environmental behavior include egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric values (Stern, Dietz, & Kalof, 1993; Steg & De Groot, 2012).

Values in Environmental Attitude

- Egoistic values relate to self-interest and concern for personal well-being, such as health or financial security. Individuals with egoistic values are motivated to protect the environment when it directly impacts them. For example, someone living near a polluted river may support environmental protection efforts to safeguard their drinking water supply.

- Altruistic values involve concern for others, including family, friends, and society at large. Individuals with altruistic values are more likely to act in environmentally sustainable ways when they believe their actions will benefit others, such as future generations or vulnerable populations.

- Biospheric values reflect concern for the environment for its own sake, recognizing the intrinsic value of ecological systems, nonhuman life, and biodiversity. People who prioritize biospheric values are likely to engage in behaviors like supporting conservation efforts or promoting biodiversity preservation because they view nature as valuable beyond its utility to humans.

Values often intersect, but they can also conflict. For instance, an individual with strong biospheric values may prioritize environmental conservation, while someone with strong altruistic values may focus more on the human impact of environmental issues. In some cases, these values can lead to conflicting decisions, such as choosing between eco-friendly products (biospheric values) or fair-trade products (altruistic values) (Steg & De Groot, 2012).

Important Theoretical Frameworks

In the context of environmental attitudes and behavior, three key psychological theories—Cognitive Dissonance Theory, Values-Beliefs-Norms (VBN) Theory, and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)—offer valuable insights into understanding how attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors are interconnected. These theories help explain why individuals may not always act in accordance with their pro-environmental attitudes, and why behavior change in the context of sustainability can be challenging.

1. Cognitive Dissonance Theory

Cognitive Dissonance Theory (Festinger, 1957) suggests that people experience psychological discomfort (dissonance) when they hold two conflicting cognitions (thoughts, beliefs, attitudes) or when their behavior contradicts their attitudes. This discomfort motivates individuals to reduce the inconsistency, often through attitude change, justification of behavior, or avoidance of conflicting information.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory (Mahmoodi-Shahrebabaki, 2015)

Application to Environmental Behavior

In the context of environmental sustainability, cognitive dissonance can occur when a person who holds pro-environmental beliefs (e.g., “I care about climate change”) engages in behavior that contradicts these beliefs (e.g., driving a car frequently, wasting energy). This inconsistency leads to discomfort, and individuals may try to reduce dissonance in various ways-

- Attitude change- The person might change their environmental attitudes to align with their behavior, convincing themselves that climate change isn’t a significant issue.

- Behavioral change- Alternatively, the individual might change their behavior to align with their attitudes, such as using public transportation or switching to renewable energy sources.

- Justification- They may justify their behavior by arguing that their individual actions don’t significantly impact the environment or by focusing on other environmental contributions, like recycling.

Understanding cognitive dissonance can help designers of sustainability interventions recognize how individuals may resist behavior change due to the discomfort that arises from this conflict. Solutions might involve creating awareness of the dissonance and encouraging small, manageable steps toward alignment between attitudes and behaviors.

2. Values-Beliefs-Norms (VBN) Theory

The Values-Beliefs-Norms (VBN) Theory, developed by Stern (2000), posits that personal values lead to beliefs about environmental problems, which in turn lead to personal norms (feelings of moral obligation to act) and ultimately influence behavior. This theory links values, beliefs, and personal norms to environmental behaviors, providing a framework to understand why some individuals act pro-environmentally while others do not.

Values Beliefs Norms Theory (Stern, 2000)

- Values- Core values shape how people perceive environmental issues. For example, individuals with biospheric values (concern for the environment for its own sake) are more likely to engage in sustainable behaviors. Those with altruistic values (concern for the welfare of others) or egoistic values (concern for personal well-being) might act based on how environmental issues affect others or themselves.

- Beliefs- The individual’s beliefs about environmental problems influence how seriously they take the issue. For example, believing that climate change is a pressing issue increases the likelihood of adopting behaviors aimed at mitigating its effects.

- Personal Norms- These are internalized feelings of obligation to take action. The theory posits that once individuals believe an environmental issue is serious and that their actions can make a difference, they experience a personal norm that compels them to act, such as reducing waste, conserving energy, or supporting environmental policies.

Application to Environmental Behavior

The VBN theory helps explain why people may fail to act environmentally despite holding pro-environmental values. For instance, even individuals who care about the environment might not act sustainably if they lack a strong belief in the urgency of the issue or do not feel a personal obligation to change their behavior. Conversely, when these beliefs and norms are aligned, individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors like recycling or reducing carbon footprints.

3. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), developed by Ajzen (1991), is one of the most widely used frameworks to understand human behavior. According to TPB, behavior is determined by three key factors-

Theory of Planned Behaviour

- Attitude toward the behavior- The individual’s positive or negative evaluation of performing a particular behavior.

- Subjective norms- Perceived social pressure to perform or not perform a behavior, based on the perceived expectations of others (family, peers, society).

- Perceived behavioral control- The individual’s perception of how easy or difficult it is to perform the behavior, which is influenced by factors such as resources, opportunities, and personal skills.

Together, these three factors influence an individual’s intention to perform a behavior, which in turn predicts actual behavior. The TPB acknowledges that behavior is not just a function of personal attitudes but also social and situational factors.

Application to Environmental Behavior

The TPB is particularly useful in understanding how pro-environmental behaviors are shaped by both individual attitudes and external factors. For example:

- An individual may have a positive attitude toward using public transportation (attitude), but if they perceive that their peers predominantly drive cars (subjective norms), or they believe that public transport is not convenient or available (perceived behavioral control), they may be less likely to use it.

- Conversely, if they believe that using public transportation will benefit the environment (positive attitude), they see it as an easy option (high perceived behavioral control), and they perceive societal pressure to act sustainably (subjective norms), they are more likely to adopt this behavior.

The TPB can also explain the attitude-behavior gap by highlighting how intentions can be influenced by external constraints, even if an individual has positive attitudes toward environmental sustainability. This suggests that interventions targeting behavioral change should not only focus on altering attitudes but also address perceived norms and control factors, such as making sustainable options more accessible and convenient.

Conclusion

Environmental attitudes and behavior are shaped by a multitude of factors, including cognitive evaluations, values, implicit attitudes, and external influences. While attitudes can inform behavior, they do not always predict it due to the interplay of these various factors. Both explicit and implicit attitudes are important in shaping proenvironmental behaviors, and the inclusion of value orientations—whether egoistic, altruistic, or biospheric—adds another layer of complexity to understanding the psychology of sustainability. Finally, the role of cultural and materialistic values further complicates the prediction of behavior but also provides opportunities for tailored environmental policies and interventions that can address specific value systems across populations.

References

Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of proenvironmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14-25.

Brown, K. W., & Kasser, T. (2005). Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of value priorities and intrinsic vs. extrinsic goals. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 197-226.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1998). Attitude structure and function. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 269-322). McGraw-Hill.

Gifford, R., & Sussman, R. (2012). Environmental psychology: A brief introduction. Psychology Press.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464-1480.

Hines, J. M., Hungerford, H. R., & Tomera, A. N. (1986). Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Education, 18(2), 1-8.

Kasser, T. (2011). Materialism and its relationship to environmental and social concerns. In T. Kasser & C. M. Sheldon (Eds.), Psychology and the Environmental Crisis (pp. 83-104). Yale University Press.

Karp, D. G. (1996). Values and their effect on proenvironmental behavior. Environment and Behavior, 28(1), 111-133.

Mahmoodi-Shahrebabaki, M. (2015). Investigating the Associations between English Language TeachersReflectiveness and Teaching Experience. International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching, 3(1), 256-272.

Schultz, P. W. (2002a). Inclusion with nature: The psychology of human-nature relations. In P. Schmuck & W. P. Schultz (Eds.), Psychology of sustainable development (pp. 61-78). Springer.

Schultz, P. W., & Zelezny, L. (2003). Reframing environmental messages to be congruent with American values. Human Ecology Review, 10(2), 126-136.

Scott, B. A., Amel, E. L., & Manning, C. M. (2021). Psychology for sustainability. Routledge.

Steg, L., & De Groot, J. I. (2012). Environmental values. In M. M. Kasser & M. L. Thompson (Eds.), Environmental psychology: An introduction (pp. 191-212). Wiley-Blackwell.

Twenge, J. M., & Kasser, T. (2013). Materialism and its implications for individual and societal well-being. Psychological Science, 24(4), 496-505.

Vantomme, D., Geuens, M., De Houwer, J., & De Pelsmacker, P. (2005). Implicit attitudes towards environmental protection: The case of the implicit association test. Environment and Behavior, 37(3), 425-449.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 16,423 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, December 26). Environmental Attitude and Behaviour- 3 Important Theories. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/environmental-attitude/