Introduction of Concept Formation Experiment

A concept in psychology refers to a mental representation or abstract idea that allows individuals to categorize and organize their experiences, objects, or phenomena into meaningful groups.

Concepts are not merely isolated thoughts but serve as essential cognitive tools that help individuals structure their understanding of the world. These mental groupings allow for efficient processing of information by organizing it into recognizable patterns, which simplifies complex stimuli.

- Cognitive Building Blocks– Concepts act as the fundamental building blocks of cognition, meaning they are integral to how humans learn, remember, and interact with the world. Without concepts, it would be challenging to differentiate between various objects, actions, and ideas.

- Facilitation of Cognitive Processe– Concepts are vital for higher-order cognitive functions. They support processes such as reasoning, allowing people to make judgments and predictions based on patterns. They also assist in decision-making by enabling quick categorizations and comparisons between different choices. Additionally, concepts enhance problem-solving abilities by providing a mental framework for interpreting new information.

Through their role in organizing mental representations, concepts provide individuals with the cognitive tools needed to interact with and adapt to their environment (Murphy, 2002).

Ten Definitions of Concept

- A concept is a mental construct that represents objects, events, or relationships and is used to organize and categorize information (Anderson, 1996).

- Concepts are fundamental building blocks of thought, allowing individuals to group and identify similarities among various experiences and objects (Rosch, 1978).

- A concept is an abstract idea or a general notion that represents a class of objects or events (Sternberg & Sternberg, 2012).

- Concepts are the mental representations that enable us to classify and understand the world around us (Murphy, 2002).

- A concept refers to a category or class of objects or events that share common characteristics (Smith & Kosslyn, 2007).

- Concepts serve as the mental shortcuts that help us to make sense of our experiences and facilitate communication (Collins & Quillian, 1969).

- Concepts are abstract ideas formed by combining experiences and knowledge, which help us to interpret and navigate the world (Gentner & Holyoak, 1997).

- A concept is a mental representation that helps individuals categorize and respond to the complexities of the environment (Barsalou, 1999).

- Concepts can be thought of as the labels we assign to our thoughts and experiences, providing a framework for understanding (Goldstone & Barsalou, 1998).

- A concept is an organized mental representation that helps to classify and interpret objects and events in our environment (Neisser, 1967).

Process of Creating a Concept

The process of concept formation in psychology involves several key steps: observation, generalization, discrimination, and abstraction. Each of these steps plays a vital role in how individuals develop and refine their understanding of concepts.

- Observation– Observation is the initial step where an individual perceives specific instances or stimuli in the environment. This involves paying attention to details and identifying features or attributes that characterize these instances. During this phase, individuals gather sensory information, which forms the basis for later cognitive processing. For example, when observing various birds, one may note common features such as feathers, beaks, and wings. This step lays the groundwork for recognizing patterns and relationships among different stimuli.

- Generalization- In the generalization step, individuals identify shared characteristics among the observed instances and create a broader category. This involves abstracting common traits from specific examples to form a more comprehensive understanding. For instance, after observing different birds, an individual may generalize that they all belong to the category “birds” due to their shared features (e.g., feathers and the ability to fly). Generalization helps in simplifying the cognitive load by allowing individuals to group similar objects or experiences under a single label.

- Discrimination– Discrimination is the ability to distinguish between different concepts or categories based on specific characteristics. This step is essential for refining understanding, as it allows individuals to recognize differences among items that may appear similar. For example, while a person may generalize all feathered creatures as “birds,” discrimination enables them to differentiate between birds and other animals, such as bats, which also have wings but are not classified as birds. Discrimination ensures that concepts are precise and helps in making accurate judgments about new instances based on their unique features.

- Abstraction– Abstraction involves extracting the underlying essence or core attributes of a concept, stripping away irrelevant details to focus on its fundamental characteristics. This step allows individuals to develop a deeper understanding of concepts beyond mere surface features. For example, the concept of “flying” can be abstracted from specific examples like birds, airplanes, or insects, leading to a broader understanding of flight as a phenomenon. Abstraction is critical for applying concepts to new situations and understanding complex ideas, as it enables individuals to recognize similarities across diverse contexts.

Concept Formation Process

These steps of observation, generalization, discrimination, and abstraction work together to facilitate the formation and refinement of concepts in psychology. Each step builds upon the previous one, enabling individuals to categorize their experiences, distinguish between different concepts, and abstract essential features for deeper cognitive understanding. This process is fundamental to learning and adapting to new information and experiences.

Types of Concepts

Concepts can be categorized based on different criteria-

- Concrete Concepts– These refer to objects or events that can be perceived through the senses (e.g., “apple,” “dog”). Concrete concepts are often easier to learn and remember due to their tangible nature.

- Abstract Concepts- In contrast, abstract concepts involve ideas or qualities that are not tangible and cannot be directly observed (e.g., “freedom,” “love”). These concepts often require higher cognitive processing and understanding (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980).

- Natural Concepts- Formed from real-world experiences, natural concepts have fuzzy boundaries and can vary in definition based on context (e.g., “furniture” may include chairs, tables, etc.). They are often learned through experience and exposure rather than formal instruction.

- Artificial Concepts- These are defined by specific rules or characteristics, often created through formal definitions (e.g., geometric shapes like “triangle” or “square”). Artificial concepts are precise and less subject to interpretation.

- Prototypes- Prototypes represent the best example or typical instance of a concept, facilitating categorization based on similarity to the ideal example (e.g., a robin as a prototype for “bird”). Prototypes help in understanding category membership and distinguishing between members (Rosch, 1975).

- Schematic Concepts- These involve mental frameworks or structures that organize information and experiences (e.g., scripts for social interactions). Schemas help individuals process information efficiently and anticipate outcomes in various situations (Bartlett, 1932).

- Categories- Categories involve the classification of concepts into hierarchies or taxonomies, aiding in the organization and retrieval of information. This hierarchical organization can be based on shared attributes or functions (Collins & Quillian, 1969).

Conceiving vs Perceiving Attitudes

Allport (1935) defined attitude as “a mental and neural state of readiness, organised through experience, and exerting a directive or dynamic influence upon the individual’s response to all objects and situations with which it is related”. read more

Perceiving Attitudes

Perception refers to the process through which individuals interpret and make sense of sensory information from their environment. It involves the immediate recognition and understanding of stimuli based on prior experiences, beliefs, and context. Perceiving attitudes are often influenced by one’s immediate emotional and cognitive responses to these stimuli, which may lead to quick judgments or impressions.

For instance, when a person enters a room and sees a group of people laughing, their initial perception might be that the group is friendly and welcoming. This interpretation is based on the visual cues of body language and facial expressions. However, this perception might be flawed; the group could be laughing at a private joke or an unrelated event, leading to a misinterpretation of the social atmosphere.

Research in social psychology, such as the work of Ambady and Rosenthal (1993), shows that first impressions based on non-verbal cues can significantly influence how individuals perceive others. Their study demonstrated that observers could accurately assess a person’s personality traits through thin slices of behaviour, highlighting the impact of perception on attitude formation.

Conceiving Attitudes

Conception, on the other hand, involves a deeper cognitive process where individuals form beliefs, opinions, or attitudes based on synthesized information and reasoning. This process often requires reflection and analysis, allowing individuals to develop more structured attitudes that may or may not align with their immediate perceptions.

Continuing with the previous example, after spending some time with the group, the person might realize that while the group initially appeared friendly, they were actually dismissive of newcomers. As a result, the individual might conceive a more critical attitude towards the group, viewing them as exclusive or unwelcoming based on accumulated observations and experiences.

Cognitive theories, such as those proposed by Festinger’s (1957) Cognitive Dissonance Theory, suggest that individuals strive for internal consistency among their beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours. When faced with conflicting information (e.g., the group’s initial friendliness versus their later exclusivity), individuals may reevaluate their attitudes to align them with their experiences and observations, illustrating the process of conceiving attitudes.

Attitudes in Concept Formation

Importance of Concepts in Psychology

- Cognitive Function- Concepts are fundamental to cognitive functions such as memory, learning, and problem-solving. They enable individuals to organize knowledge, facilitate understanding, and enhance cognitive efficiency (Anderson, 2005).

- Communication- Concepts provide a common language for discussing complex topics, allowing effective communication and shared understanding in interpersonal interactions (Vygotsky, 1986).

- Decision-Making- Concepts guide decision-making processes by simplifying information and allowing for quick evaluations of options based on category membership. They help individuals navigate choices by leveraging their existing knowledge (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981).

- Theoretical Development- In psychology, concepts are foundational for developing theories and models that explain human behavior and mental processes. They enable researchers to construct frameworks that facilitate the understanding of psychological phenomena (Neisser, 1967).

- Social Understanding- Concepts shape social understanding by influencing how individuals categorize and interpret social cues and behaviors. This impacts social perception, stereotypes, and interactions with others (Fiske, 1993).

Goldstein’s Experiment on Concept Formation

Goldstein’s experiments on concept formation primarily focused on understanding how individuals develop and refine concepts through experiential learning. His work aimed to identify the cognitive processes involved in forming concepts and the ways in which these processes differ among individuals.

Goldstein conducted experiments with a diverse group of participants to observe how they formed concepts based on specific stimuli. The participants were exposed to various objects and were asked to categorize them according to shared characteristics.

The experiment often included tasks where participants had to identify similarities and differences among the objects presented to them.

Observational Learning

A significant finding from Goldstein’s research was the role of observational learning in concept formation. Participants demonstrated that they could form concepts not only through direct experience but also by observing others interacting with different objects and categories.

This highlighted the importance of social learning in developing concepts, as individuals could acquire new categorizations based on their observations of others.

Goldstein’s Process of Concept Formation

Goldstein identified several cognitive processes involved in concept formation, including

- Categorization- The ability to group objects based on shared characteristics.

- Comparison- Participants often compared objects to establish commonalities and differences, which aided in categorization.

- Feedback Mechanisms- The experiments emphasized the importance of feedback in refining concepts, as participants adjusted their categorizations based on success or errors in their initial groupings.

Goldstein concluded that concept formation is a dynamic process involving interaction between sensory experiences, social observation, and cognitive reasoning. He emphasized that this process could vary significantly among individuals based on their prior experiences and learning environments.

Vygotsky’s Concept Formation Idea

Lev Vygotsky, a prominent Russian psychologist, contributed significantly to understanding concept formation through his sociocultural theory of cognitive development. His ideas emphasize the influence of social interaction, culture, and language in shaping an individual’s cognitive processes.

Key Components of Vygotsky’s Concept Formation

- Social Interaction– Vygotsky argued that social interactions are fundamental to concept formation. He believed that learning is inherently a social process, and concepts are developed through communication and collaboration with others. Through dialogue and interaction with more knowledgeable peers or adults, individuals can gain new perspectives and refine their understanding of concepts.

- Language and Thought– Vygotsky posited that language plays a crucial role in cognitive development. He suggested that children internalize language and use it as a tool for thought, allowing them to form and manipulate concepts. He emphasized the idea that thought and language are intertwined; as individuals acquire language, they can articulate their thoughts and concepts more effectively.

- Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)– Vygotsky introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development, which refers to the range of tasks that a learner can perform with the guidance of a more knowledgeable individual but cannot yet accomplish independently. In this context, concept formation occurs when learners are guided through tasks that challenge their current understanding, fostering the development of more complex concepts.

- Cultural Context- Vygotsky highlighted the importance of cultural context in shaping concept formation. He believed that different cultures provide unique tools and symbols that influence how individuals categorize and understand their experiences. The cultural framework informs the content and structure of concepts, demonstrating that concept formation is not a universal process but one that is shaped by cultural norms and practices.

Object Formation Test

The concept formation test developed by Vygotsky features a set of 32 blocks in five colours (red, green, yellow, blue, and white). These blocks come in seven distinct shapes: circle, semi-circle, square, triangle, hexagon, cylinder, and trapezoid. The blocks are categorized into four groups identified by the symbols MUR, LAG, BLK, and CEV. Specifically, the blocks labelled LAG are characterized by uniform height and width, while those marked MUR have a height of 2 cm and a smaller width. The blocks designated as CEV are 8 cm tall with a smaller width, and the BLK blocks are also 8 cm tall but feature a larger width.

This test was later revised by Haufman and Kasanin, who streamlined the assessment to consist of 22 blocks in five different colours and six distinct shapes. Their revision introduced two height variations and two size options for the blocks, enhancing the test’s capacity to evaluate concept formation more effectively.

Statement of the Problem

To study the process of concept formation that takes place with respect to the present subject & state whether he/ she had the perceiving attitude or conceiving attitude.

Material of Concept Formation Experiment

- Haufman and Kasanin Test-The test consists of 22 wooden blocks. The blocks are of (five different colours), six different shapes, two different heights- tall and flat, and two different sizes- large and small. The blocks are having non- sense syllables at the bottom. These are used to define the group type.

- Stop watch

- Result table

- Stationary

- Wooden screen

Criteria Used

1.MUR – Tall & Small

2.CEV – Flat & Small

3.LAG – Tall & Large

4.BIK – Flat & Large

Instructions for Concept Formation Experiment

“Here there are four kinds of blocks and you will have to arrange them in four groups on the basis of a principle which you discover suitable for the task.”

“You will have to only move them and should not lift or tilt them in your performances. After classifying them into four groups tell me what idea or principle you have used for this. There is no time limit for this. You can take your own time. When I say, ready go, you must start the task. Now ready go.”

Plan of Concept Formation Experiment

Plan of the Experiment

Procedure of Concept Formation Experiment

Participants will be presented with a set of blocks from the test, which will be rearranged and laid out on the table with the symbols marked on them facing away from the participants. Clear instructions will be provided, informing participants that their goal is to classify the blocks based on specific criteria they determine.

Once the instructions are given, the clock will start to measure the time taken for the participant to classify the blocks, ensuring they understand they can take their time to think through their classification. As the participant works on classifying the blocks, observers will note the time taken for the classification task, which will serve as an important metric for evaluating their performance.

After completing the classification, the participant will explain the criteria they used to organize the blocks, discussing their thought process, the characteristics they focused on (such as color, shape, size, or height), and any challenges they encountered during the task.

Finally, the time taken for classification and the participant’s explanations will be documented, providing valuable information for analyzing their concept formation strategies and cognitive processes.

Precautions of Concept Formation Experiment

- Participant Comfort- Ensure that the testing environment is comfortable, quiet, and free from distractions to help participants focus on the task.

- Clear Instructions- Provide clear, concise instructions to participants before starting the test. Make sure they understand the task requirements, including how to classify the blocks and the importance of articulating their criteria.

- Familiarization- Allow participants a brief period to familiarize themselves with the blocks before starting the classification task. This can help reduce anxiety and improve their performance.

- Monitoring Time- Use a reliable timing method to track the duration of the classification task. Make sure participants know when the time starts and stops to ensure accurate time measurement.

- Neutral Facilitation- Ensure that the facilitator remains neutral during the task and does not provide cues or hints that could influence participants’ classifications.

- Documentation- Have a systematic approach for documenting the time taken and participants’ explanations. Use clear notes to capture their reasoning accurately without bias.

- Debriefing- After the task, conduct a debriefing session to discuss participants’ experiences. This can help clarify any misunderstandings and gather qualitative data on their thought processes.

- Ethical Considerations- Ensure informed consent is obtained from all participants, explaining the purpose of the experiment and how their data will be used. Ensure confidentiality and anonymity in reporting results.

- Consistent Setup- Maintain a consistent arrangement of blocks for each participant to ensure that variations in setup do not affect classification outcomes.

By implementing these precautions, the experiment can be conducted more effectively and ethically, ensuring valid and reliable results while respecting the participants’ experiences.

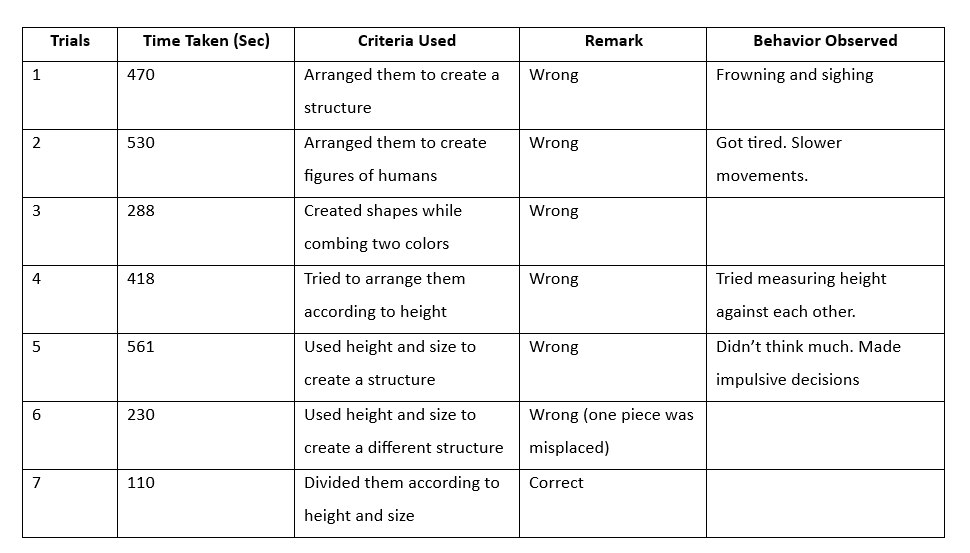

Result Table of Concept Formation Experiment

Result Table of Concept Formation Experiment

Interpretation of Concept Formation Experiment

The participant’s performance in the concept formation test reflects a learning curve that parallels the processes of perceiving and conceiving attitudes. Initially, the participant displayed a tendency to engage in creative and imaginative classification, as seen in the first few trials where they attempted to arrange the blocks into structures and figures of humans. This mirrors the perception stage, where individuals gather sensory information and form initial impressions based on their experiences and expectations. However, like perception, which may sometimes lead to misinterpretation or superficial understanding, the participant’s early classifications were deemed incorrect because they lacked alignment with the specified criteria.

As the trials progressed, the participant began to refine their approach by focusing on relevant attributes such as height and size, demonstrating a shift towards a more structured and analytical mode of thinking. This transition resembles the conception phase, where individuals synthesize their perceptions into coherent attitudes or beliefs based on deeper understanding and reasoning. By the final trial, the participant successfully categorized the blocks in just 110 seconds, indicating a clear alignment with the task requirements. This evolution from initial misclassifications to a correct and efficient response underscores the dynamic interplay between perception and conception in forming attitudes, highlighting how individuals can adapt and refine their cognitive strategies through experience and practice.

Conclusion

Concept formation is a fundamental cognitive process that enables individuals to categorize and organize their experiences, facilitating understanding and interaction with the world around them. This process involves several key steps, including observation, generalization, discrimination, and abstraction, which collectively aid in the creation of mental representations or concepts.

The exploration of concept formation through structured experiments, such as Vygotsky’s test and its subsequent revisions, provides valuable insights into how individuals develop their classification strategies and reasoning skills.

The findings from such experiments reveal that concept formation is not a static ability; rather, it is a dynamic process that evolves through practice and adaptation. As individuals encounter new information and experiences, they refine their cognitive frameworks, enhancing their capacity to perceive and categorize various phenomena effectively.

Ultimately, understanding concept formation is crucial for educators, psychologists, and researchers, as it plays a vital role in learning, problem-solving, and the development of critical thinking skills, contributing significantly to cognitive development throughout an individual’s life.

References

Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R. (1993). Thin slices of behavior as a basis for judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(3), 431–441. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.3.431

Anderson, J. R. (2005). Cognitive psychology and its implications (6th ed.). Worth Publishers.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Collins, A. M., & Quillian, M. R. (1969). Retrieval of information from semantic memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 8(2), 240-247.

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Fiske, S. T. (1993). Controlling other people: The impact of power on stereotyping. American Psychologist, 48(6), 621-628.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Murphy, G. L. (2002). The Big Book of Concepts. MIT Press.

Neisser, U. (1967). Cognitive psychology. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Piaget, J. (1970). The science of education and the psychology of the child. Orion Press.

Rosch, E. (1975). Cognitive representations of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 1(4), 494-503.

Rosch, E. (1978). Principles of categorization. In E. Rosch & B. B. Lloyd (Eds.), Cognition and categorization (pp. 27-48). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. MIT Press.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 16,458 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, September 25). Concept Formation Experiment- Master Conducting the Experiment and Explore 10 Definitions of Concept. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/concept-formation-experiment/