Sports performance is significantly influenced by arousal, a psychophysiological state of awareness and preparedness. Arousal and performance have a complicated relationship that has been the focus of much sports psychology study.

Defining Arousal

The concept of arousal is complex and includes emotional, cognitive, and physiological elements. Arousal physiologically entails modifications to the autonomic nerve system, including elevated heart rate, breathing, and tense muscles. Arousal has a cognitive impact on focus, attention, and judgment. Arousal is linked to emotions such as motivation, worry, or enthusiasm. Arousal in sports can vary from strong enthusiasm or anxiety to a condition of calm attention.

Theories of Arousal and Performance

Inverted-U Hypothesis

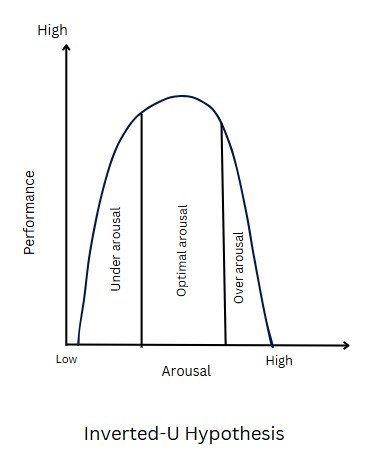

One of the most well-known hypotheses in sports psychology is the inverted-U hypothesis. It implies that there is an ideal arousal level for optimal performance. This hypothesis states that performance rises with arousal until a certain degree, at which time performance starts to fall as arousal rises further. The best performance is linked to moderate levels of arousal, resulting in an inverted U-shaped curve.

The sport, the particular skill being performed, and the individual athlete all influence the ideal level of arousal. For example, activities requiring accuracy and precise motor control, like shooting an archer or putting in a round of golf, would be better done at lower arousal levels. On the other hand, higher levels of arousal may be advantageous for activities like weightlifting or sprinting that require strength, power, and gross motor abilities.

Inverted U hypothesis

Individual Zones of Optimal Functioning (IZOF)

Hanin (1989) created the IZOF model, which highlights the unique character of the arousal-performance relationship. It suggests that every athlete has a distinct range of arousal levels that they may operate in to perform at their peak. Contrary to what the inverted-U hypothesis suggests, this zone is not always at the middle of the arousal continuum. While certain athletes may flourish at high levels of arousal, others may perform best at low levels.

The emotional aspect of arousal is also considered by the IZOF model. It implies that both happy and negative emotions have the potential to affect performance, but only if they are within the specific range of an athlete’s best functioning. Positive feelings like excitement and enthusiasm, for instance, can be experienced by an athlete who performs best at high levels of arousal, improving their performance. Their performance may be hampered, though, if their arousal level becomes too high and they start to feel anxious or afraid.

IZOF

3. Catastrophe Theory

Hardy and Fazey’s (1987) disaster theory provides a more intricate explanation of the connection between arousal and performance. It implies that the link between physiological arousal and performance exhibits an inverted-U pattern when cognitive anxiety (worry and apprehension) is low. Increases in physiological arousal, however, can cause a sharp and abrupt drop in performance due to high levels of cognitive anxiety—a “catastrophe.”

According to the catastrophe theory, it is similarly difficult to reverse the performance fall. Reducing arousal alone might not be sufficient to recover performance if an athlete has suffered a catastrophic decline brought on by excessive arousal and worry. Before the athlete can resume performing at their best, they might need to deal with their cognitive fear and rebuild their confidence.

Catastrophe theory

Research Findings

Numerous studies have investigated the arousal-performance relationship in sports. While the inverted-U hypothesis has received some support, research has also highlighted the importance of individual differences and the role of cognitive anxiety.

Individual differences: Research has indicated that the ideal levels of arousal for athletes vary widely. While some athletes prefer lower levels of arousal, others regularly do better in high-arousal situations. This bolsters the IZOF paradigm and highlights the necessity of tailored arousal management strategies.

Cognitive anxiety: Studies have shown that the relationship between arousal and performance can be considerably impacted by cognitive anxiety. Even mild degrees of physiological arousal can impair performance in athletes who are experiencing high levels of anxiety and fear. This demonstrates the significance of controlling cognitive worry in sports and lends credence to the disaster theory. Emotional factors: Research has also looked into how emotions relate to the relationship between arousal and performance. Excitation and enthusiasm are examples of positive emotions that might improve performance when they are within. However, negative emotions, such as anxiety and fear, can impair performance, particularly when they exceed the athlete’s optimal zone.

Practical Implications

Understanding the arousal-performance relationship has important practical implications for athletes, coaches, and sports psychologists.

Customized arousal control: Before and during competition, athletes should learn to recognize their individual ideal arousal levels and create plans to control them. This could entail methods like attentional control, visualization, self-talk, and relaxation exercises.

Cognitive anxiety management: By training athletes cognitive restructuring strategies, such as questioning negative beliefs and substituting them with constructive and positive ones, coaches and sports psychologists can assist athletes in managing cognitive anxiety.

Emotional control: To control both good and negative emotions, athletes should be encouraged to hone their emotional control abilities. This could entail methods like acceptance, reassessment, and emotional awareness.

Performance under pressure: By practicing challenging competing scenarios, athletes can learn how to perform under pressure. This can assist them in creating coping skills.

Conclusion

In sports, the relationship between arousal and performance is a complicated and multidimensional issue. Although the inverted-U hypothesis offers a broad framework for comprehending this relationship, studies have emphasized the significance of individual differences, emotional factors, and cognitive anxiety. This information can be used by athletes, coaches, and sports psychologists to create customized plans for controlling emotions, managing cognitive anxiety, and managing arousal in order to improve athletic performance.

Read more about Impact of stress and anxiety in sports

References

- Cox, R. (2006). Sport Psychology. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Jarvis Matt (2006). Sport Psychology : A student’s Handbook. Routledge

- Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. https://zenodo.org/records/1426769/files/article.pdf

- Hardy, L., & Parfitt, G. (1991). A catastrophe model of anxiety and performance. British journal of psychology (London, England : 1953), 82 ( Pt 2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1991.tb02391.x

- Wrisberg, Craig. (1994). The Arousal-Performance Relationship.. Quest. 46. 10.1080/00336297.1994.10484110.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 16,504 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, March 12). Arousal and Performance Relationship in Sports. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/arousal-and-performance/