Introduction

Measurement and evaluation are critical processes in psychological research and testing, forming the foundation for understanding human behavior and mental processes. Measurement involves assigning numbers or symbols to attributes of phenomena based on specific rules, while evaluation interprets these measurements to derive meaningful insights (Anastasi, 1988). Accurate measurement ensures that psychological constructs, such as intelligence, personality, and attitudes, can be quantified, compared, and analyzed scientifically.

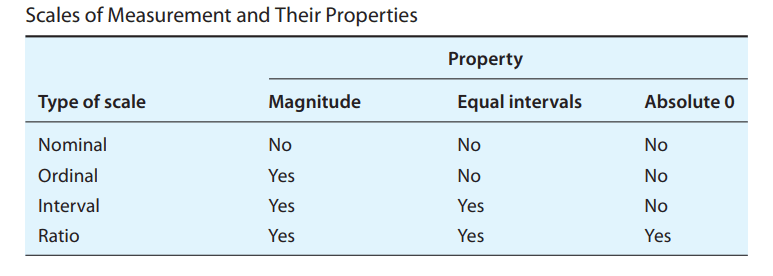

An essential element of measurement is understanding the 4 scales of measurement, which define the properties of data and dictate the statistical techniques appropriate for analysis and the 2 types of measurements in general.

Stanley Smith Stevens (1946) classified measurement into four scales- nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio. These scales vary in complexity and applicability, each serving unique functions in psychological research and testing (Kaplan & Saccuzzo, 2017).

Read More- Psychological Testing

Scales of Measurement

The four major types of scales are-

Properties of Scales of Measurement

1. Nominal Scale-

The nominal scale is the most basic form of measurement. It categorizes data into distinct, non-overlapping groups that have no inherent order or numerical meaning. This scale is typically used for labeling variables with qualitative attributes.

Characteristics of the scales includes-

- Mutually Exclusive Categories- Each data point belongs to only one category (e.g., a person can belong to only one diagnostic group).

- No Logical Order- Categories do not have a rank or sequence.

- Limited Descriptive Statistics- Only mode and frequency counts are meaningful as measures of central tendency.

Some examples of a nominal scale include- patients classified as having anxiety disorders, mood disorders, or personality disorders (DSM-5). It can also include data with labels like male, female, or nonbinary participants in a study.

2. Ordinal Scale

The ordinal scale extends the nominal scale by introducing a logical order to the categories. However, it does not quantify the differences between categories, making it less precise than higher-order scales.

Characteristics of the scales includes-

- Ranked Categories- Data points are organized in a meaningful sequence (e.g., low to high).

- Unequal Intervals- The distance between ranks is not consistent or meaningful.

- Median and Percentiles- These are the most useful measures of central tendency and dispersion.

Some examples of a nominal scale include- used for assessing opinions or attitudes (e.g., a scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”). It includes classifications like low, middle, or high.

3. Interval Scale

The interval scale is more advanced, as it not only ranks data but also ensures that the intervals between values are equal. However, it lacks a true zero point, which limits certain types of analysis, such as ratio comparisons.

Characteristics of the scales includes-

- Equal Intervals- The difference between two consecutive points is the same throughout the scale.

- No True Zero- The absence of a true zero point means ratios are not meaningful.

- Mean and Standard Deviation- These statistical measures are meaningful and commonly used.

Some examples of a nominal scale include- intelligence tests (e.g., WAIS) measure IQ on an interval scale, where equal differences represent equal changes in the construct. It is used in biofeedback studies, measured in Celsius or Fahrenheit.

4. Ratio Scale

The ratio scale is the most precise and informative scale of measurement. It possesses all the properties of an interval scale but includes a true zero point, allowing for meaningful ratio comparisons.

Characteristics of the scales includes-

- True Zero- A point of absolute absence of the variable being measured (e.g., zero seconds means no elapsed time).

- Equal Intervals- The distance between any two consecutive points is consistent.

- All Statistical Operations- Arithmetic operations, including ratios and percentages, are valid.

Some examples of a nominal scale include- measured in milliseconds to evaluate cognitive processing. The total number of correct answers on a memory test.

Scales of Measurement

Read More- Types of Psychological Tests

Types of Measurements- Psychological Vs Physical

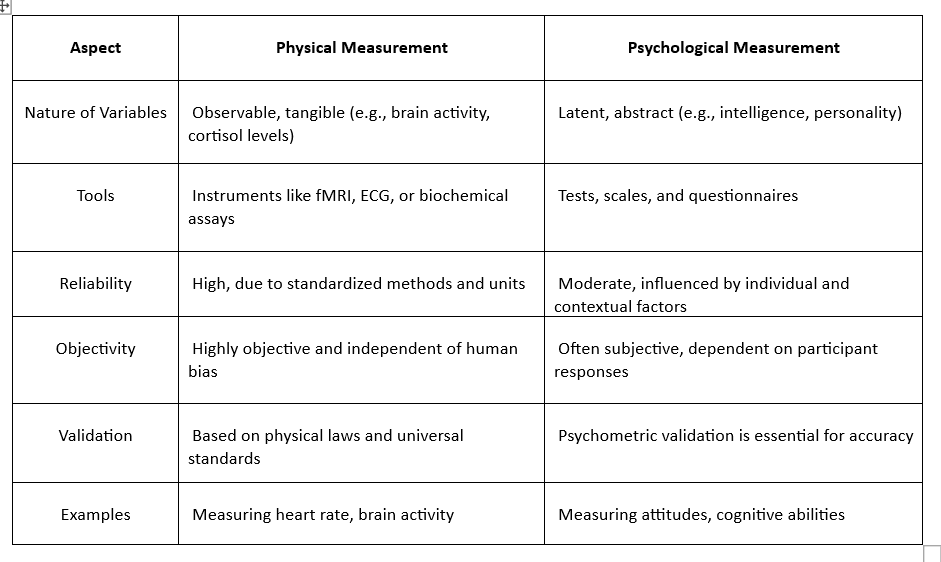

Psychological and physical measures are different from each other in terms of what they measure and how they are constructed.

1. Physical Measurement

Physical measurement involves the direct quantification of observable and often biological attributes using standardized tools. These measurements are commonly employed in psychology as indicators of physiological states or processes, which can be correlated with psychological phenomena.

The key characteristics of physical measurement includes-

- Objective- Physical measurements rely on standardized instruments and methods, minimizing subjective bias.

- Repeatable- Results are consistent when the same conditions and tools are used, enhancing reliability.

- Standardized Units- Measurements are expressed in universally recognized units, such as seconds, millimeters, or micrograms per deciliter.

- High Precision- Advances in technology, such as neuroimaging or biochemical assays, provide highly accurate and detailed data.

Some examples of physical measurement in psychology are-

- Brain Activity Using fMRI- Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) captures real-time neural activity by detecting changes in blood flow, providing insight into brain regions involved in specific tasks or disorders.

- Cortisol Levels to Assess Stress- Cortisol, a stress hormone, can be measured in saliva or blood samples to quantify physiological stress responses.

- Heart Rate and Galvanic Skin Response- Tools like ECG (electrocardiography) or GSR (galvanic skin response) measure autonomic nervous system activity.

Advantages and Limitations of Physical Measurements

The key advantages of physical measurement are-

- Reliability- Standardized tools and methods ensure consistent results.

- Objectivity- Data is not influenced by the researcher’s or participant’s perceptions.

- Applicability Across Contexts- Physical measurements can be used in diverse environments, including laboratories and field settings.

The key limitations of physical measurement are-

- Limited Psychological Interpretation- While precise, physical measurements often require additional psychological data to provide meaningful insights into behavior or cognition.

- Cost and Accessibility- Equipment like fMRI machines can be expensive and resource-intensive.

2. Psychological Measurement

Psychological measurement addresses intangible constructs, often referred to as latent variables, such as intelligence, personality, attitudes, or mental health. Since these constructs are abstract, they are measured indirectly through tests, scales, and questionnaires that are designed based on theoretical and operational definitions.

The key characteristics of psychological measurement includes-

- Subjective Elements- Psychological data often depend on individuals’ self-reports, interpretations, or behaviors, which can introduce variability.

- Latent Constructs- Constructs like anxiety or motivation cannot be observed directly but are inferred through indicators or items on a test.

- Reliability and Validity- Psychological measurements require rigorous psychometric validation to ensure accuracy and generalizability.

- Influence of Context- Factors like culture, language, and testing conditions can affect responses and outcomes.

Some examples of psychological measurement in psychology are-

- Intelligence Tests- Tools like the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) measure cognitive abilities across various domains, such as verbal comprehension, working memory, and processing speed.

- Personality Assessments- Instruments like the Big Five Inventory (BFI) evaluate traits such as extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism based on established psychological theories.

- Attitude Scales- Likert scales assess attitudes toward specific topics by measuring agreement or disagreement with statements.

Advantages and Limitations of Physical Measurements

The key advantages of psychological measurement are-

- Captures Complex Constructs- Psychological tests can quantify multifaceted traits like empathy, resilience, or creativity.

- Theoretical Basis- Measurements are grounded in psychological theories, providing a conceptual framework for interpretation.

- Practical Applications- Psychological measures are versatile tools for therapy, education, and workplace evaluations.

The key limitations of psychological measurement are-

- Subjectivity- Responses may be influenced by social desirability bias, self-awareness, or situational factors.

- Cultural Sensitivity- Constructs and test items may not be universally applicable or valid across different cultural contexts.

- Indirectness- Since constructs are latent, measurements rely on operational definitions, which may vary by researcher or context.

Physical vs Psychological Measurement

Conclusion

Measurement and evaluation are foundational components of psychological research, offering systematic ways to quantify and interpret human attributes and behaviors. The four scales of measurement—nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio—provide distinct frameworks for organizing and analyzing data, each tailored to specific types of variables and research goals. Nominal and ordinal scales are suited for categorical and ranked data, respectively, while interval and ratio scales allow for more precise quantitative analysis.

The distinction between physical and psychological measurement underscores the diverse nature of psychological research. Physical measurements provide objective, reliable data about observable attributes, often serving as physiological indicators of mental processes. Psychological measurements, on the other hand, address latent constructs like intelligence, personality, and attitudes, necessitating rigorous psychometric validation to ensure accuracy and applicability.

References

Anastasi, A. (1988). Psychological Testing (6th ed.). New York: Macmillan.

Kaplan, R. M., & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2017). Psychological Testing: Principles, Applications, and Issues (9th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Stevens, S. S. (1946). On the theory of scales of measurement. Science, 103(2684), 677–680.

Gregory, R. J. (2014). Psychological Testing: History, Principles, and Applications (7th ed.). Pearson.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 16,611 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, December 7). 2 Important Types of Measurements. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/2-important-types-of-measurements/